Across the nation, veterans who rely on the VA for kidney transplants are less likely to actually receive a transplant - and more likely to die waiting - compared with other patients in need of the same surgery, according to a new study by researchers at the Cleveland Clinic and Cleveland VA.

“What we found, on a national level, was that VA patients had fewer transplants over time compared to patients with either private insurance or Medicare insurance,” said Dr. Joshua Augustine of the Cleveland Clinic, one of the study’s lead authors.

Those findings mirror concerns raised in a joint investigation by KARE 11 and other TEGNA television stations last year. The investigation documented how sick veterans were being forced to travel long distances to get their operations, sometimes with deadly consequences.

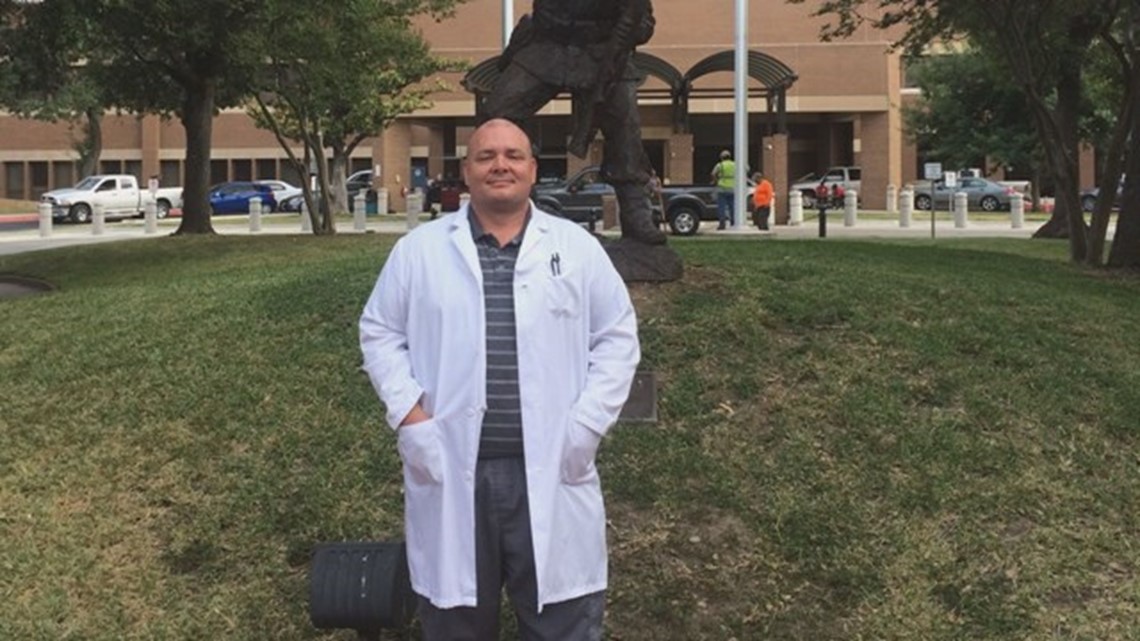

“How many patients do you think unnecessarily died?” VA whistleblower Jaimie McBride was asked.

“Thousands,” replied McBride, a VA Transplant Program Manager from San Antonio, Texas.

McBride provided KARE 11 with records showing he had been sounding the alarm to officials in Washington about deadly delays in the VA’s transplant program.

“The problems have not been solved. Period,” he said at the time.

Study details

In the new study, researchers looked at all U.S. adult patients on the kidney transplant list between 2004 to 2016. Results indicated veterans using the VA were 28% less likely to undergo a transplant than patients with private insurance.

Although demographic differences may also play a role, researchers suggested a notable difference was the distance VA patients had to travel to a transplant center.

“The average distance for VA patients to travel to a VA transplant center when we looked at the data was 280 miles,” Augustine told KARE 11. “And this compared to just over 20 miles for non-VA patients.”

“So, the distance itself appeared to be a big barrier for transplantation,” he added.

The findings were presented last month at a conference sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology, a leading organization of physicians and scientists who study kidney disease.

A Minnesota example

A Minnesota widow believes her husband’s case is a prime example of how the distance veterans are forced to travel keeps them from receiving the transplant they need to survive.

John Moore had to travel repeatedly to a VA hospital in Texas. The Army veteran died waiting for a liver transplant.

“And he didn’t get it,” Pam Moore said. “My husband should have been home. Not in Texas.”

After KARE 11 aired a series of investigative reports in 2016 called “Distance, Delay and Denial,” members of Congress promised to review the issue.

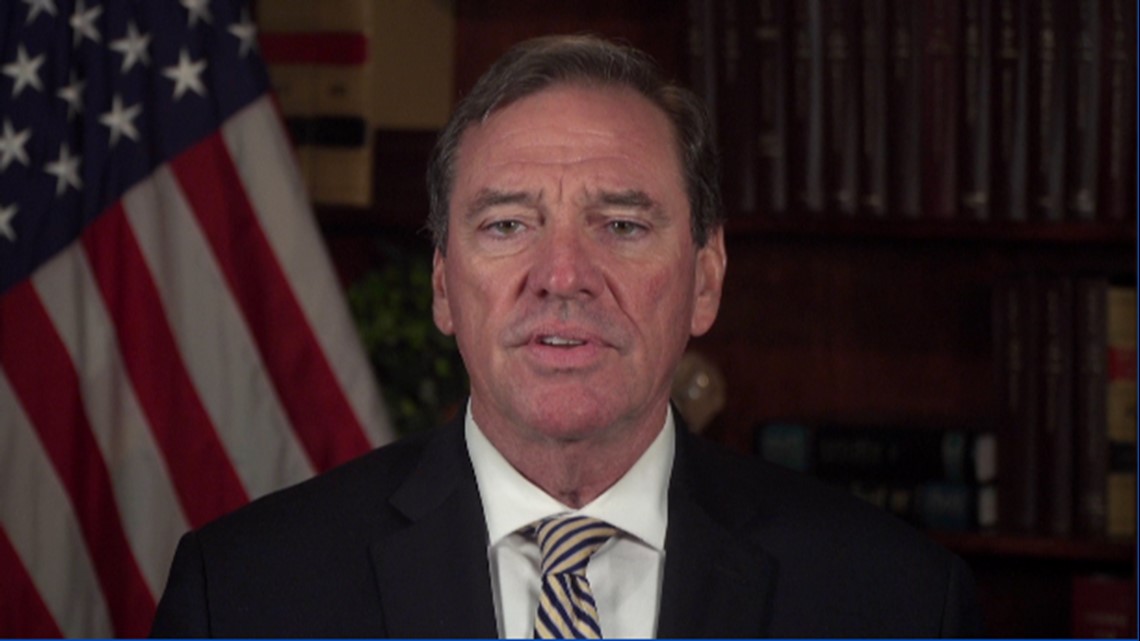

Rep. Neal Dunn (R-FL), a former Army surgeon, says KARE’s investigation revealed a flawed VA system that put veterans at risk.

“I applaud you. I read your article on the subject – outstanding,” Dunn told KARE 11. “It’s hard to imagine a bureaucracy actually comes up with answers like that.”

Proposed changes

To fix the problem, Dunn introduced the “Veterans Increased Choice for Transplanted Organs and Recovery (VICTOR) Act of 2017.” As approved by the House, it would allow veterans who live more than 100 miles from one of the nation’s VA transplant centers to seek care at a non-VA facility.

“Once you lay out the facts for everybody, it’s pretty obvious that this is the right way to proceed,” Dunn said. “The VICTOR Act will remove unnecessary obstacles facing veterans in need of organ transplants, making it easier for those who have served our country to receive life-saving surgery,” he added.

However, the Senate has yet to take up the bill.

Hoping to speed action, this week Dunn introduced a similar amendment to the Care in the Community Act.

That sweeping piece of legislation is designed to replace the current VA Choice program which allows veterans facing lengthy delays or long-distance travel to get care at non-VA facilities in their own communities.

Funding for that program is currently a major point of contention in Congress.

While lawmakers debate the issue, one of the authors of the new study says he believes allowing veterans to get transplants closer to home could increase the rate of life-saving operations.

“If patients are hundreds of miles away, they may not be immediately ready to travel to receive a deceased donor kidney transplant,” said Dr. Augustine. “Typically, patients need to travel within just a few hours to a transplant center in order to receive such a transplant.”

If you have a suggestion for a KARE 11 investigation,

or want to blow the whistle on fraud or government waste, email us at: