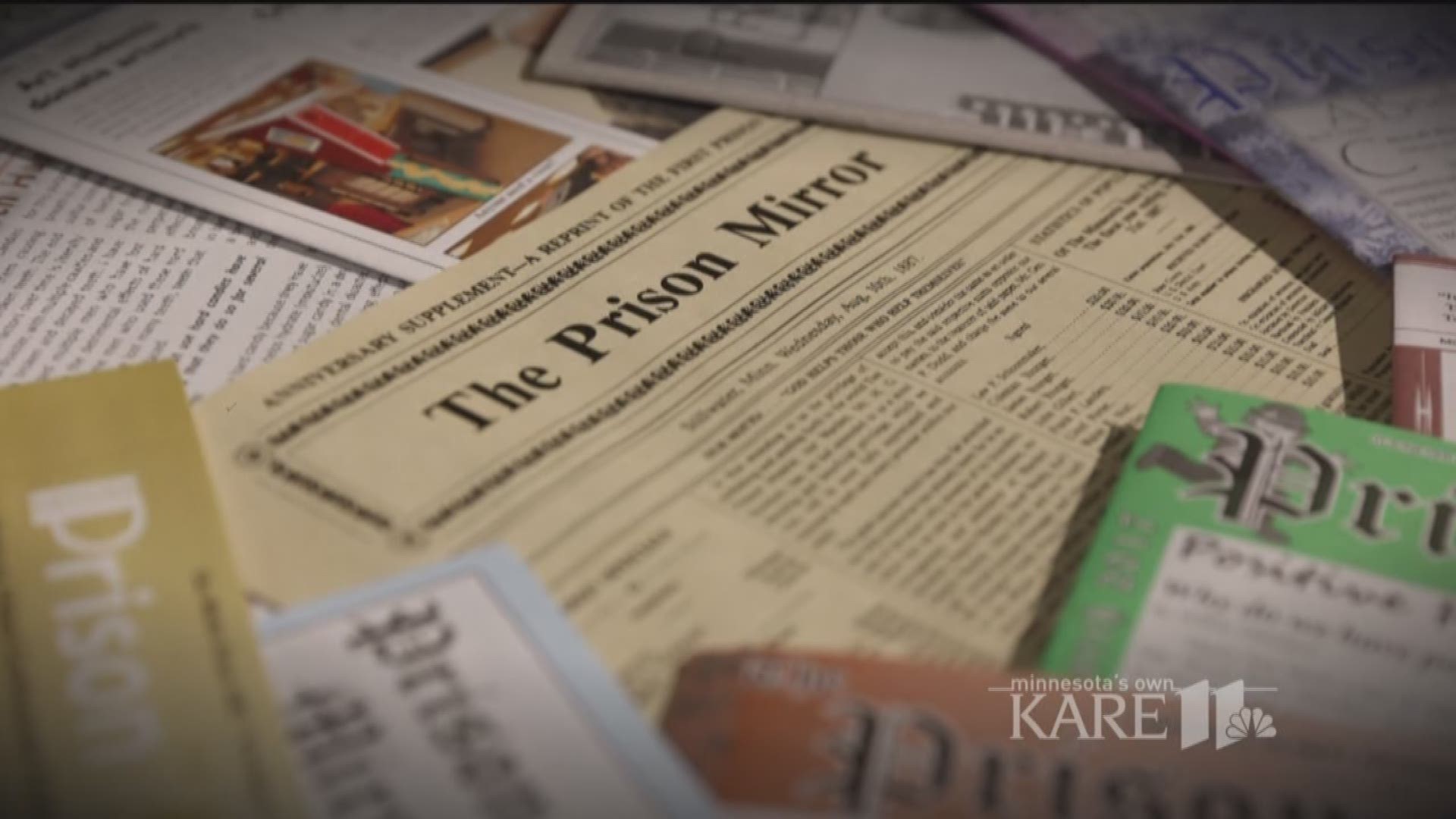

In the first issue published Wednesday, Aug. 10, 1887, the founders – which included James, Cole and Robert Younger of the James-Younger gang – wrote what they saw as the vision of the paper.

"It shall be the untiring mission of the "MIRROR" to encourage prison literary talent and to instruct, assist, encourage, and entertain all those within our midst..."

They committed to including prison news, jokes, poetry and sketches. And the prisoners also saw themselves as providing a cautionary tale.

"...it will contain each week words of warning to the young, from the pens of those who know whereof they speak, in verification of that great scriptural truth 'the way of the transgressor is hard.'"

Now, 130 years later, the mission is still clear, and the inmates of the Minnesota Correctional Facility-Stillwater are still writing their stories.

“I didn't really understand the gravity of it until I got through the archives and was like ‘Wow,’” said the current senior editor of The Prison Mirror, who the MN Department of Corrections asked we do not identify by name. “2017, that's a long way from 1887.”

The Prison Mirror is the longest continuously running prison newspaper in the U.S. Over the decades, its contributors have covered women's suffrage and labor strikes of the early 20th Century, inmate reactions to various wars, the deadly A-Block rampage of 1975, and the first Prison Mirror computers in the 1980s.

“The population who we make the paper for, they view this as their outlet to be heard and want to see things that are important to them,” said another one of the current editors of the paper.

The dynamic of an inmate-run paper in a place where they have no control is rather complex. The editors say the content starts with what interests them and the greater population of 1,600 inmates, but they walk a tight rope, not to offend any offenders and not to upset the guards or administration.

Ultimately, the warden signs off on every monthly edition.

“We allow them a certain amount of editorial freedom to discuss if we are making policy changes if that will affect them,” said Victor Wanchena, associate warden of the MCF-Stillwater. “To that end, it has to be done in a respectful and positive manner.”

The average sentence length in Stillwater is eight years, according to Wanchena. The number of inmates serving life is about 14 percent of the population.

“Ninety-six percent of all offenders get released,” said Martin Hawthorne, a vocational instructor at the prison who oversees daily operations of the paper. “So what are you going to do? You going to stick them in a cage, in a box, treat them roughly and then let them out and expect them to not return to the ways that got them incarcerated?”

As The Mirror said in its first edition and what inmates say today, it “sheds a ray of light behind those who are behind bars.”