MINNEAPOLIS — It's a brisk fall morning at Lyndale Community School, and students arrive bundled in coats, wearing their backpacks.

Many students arrive with their parents or walk, as many families live close enough to the school to not have to take the bus.

"Good morning! Are you sleepy?" Principal Meghan O'Connor calls out to a girl. She rubs her eyes as she walks into the entrance.

"We are a very diverse school," O'Connor said. "So we have a lot of Somali American students, African American — a lot of Latino students. We have several students who are new to the country."

O'Connor said this is her third year at Lyndale. When she arrived, the work to launch the Somali Heritage Program had already begun. Lyndale has a student body of 420 — 100 to 120 of whom, O'Connor said, are Somali.

One year into launching the program, word has spread that Lyndale is the place kids come to learn in both English and Somali. O'Connor said that's a point of pride for them; something they tout so more families would consider attending Lyndale.

"A lot of our Somali students at this point were born here or their parents were born here," O'Connor said when asked why the program was so important for the school. "Lots of families feel this disconnect where our Somali students don't know how to speak Somali."

The assistant principal, Hanna Haileyesus, said she can relate to a lot of the students at Lyndale because she is Ethiopian American.

"I tried so hard to be American," she said. "You don't learn that having two cultures is a positive until you're older. As a young kid, I wanted to blend in and not stand out."

She said her family also went through what a lot of the Lyndale families are currently going through.

"You come to a different country, you try to assimilate, you try to blend and then you grow up kind of regretting forgetting your own culture," she said. "You've picked up a whole new one; we want to interrupt that and quickly show them that it is a beautiful thing to have both."

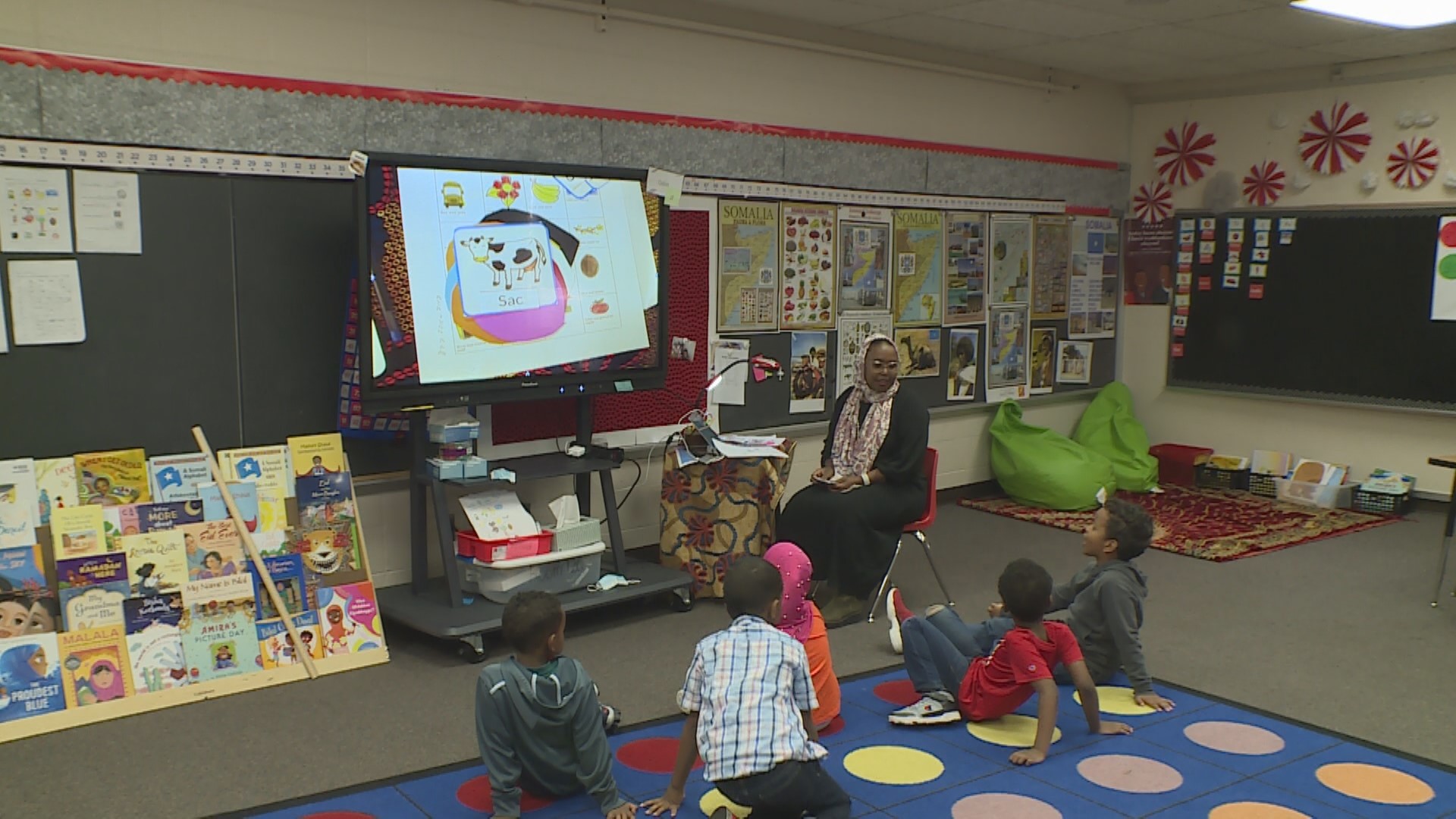

Inside Ms. Farhiya Del's classroom, the elementary school kids have both. Del weaves in and out of English and Somali, teaching the young ones how to say numbers, colors and other words in Somali.

"If the parents don't speak English, the children don't speak Somali, they would need a translator," Del said. "They won't even understand each other."

That's something she's trying to prevent. She expressed regret that she didn't teach her own children Somali more. She said when she speaks to them in Somali, they understand, but they often reply in English.

She also said a big part of her education's purpose is to also normalize a dual-language home.

"There's no shame in speaking your language anywhere," she said. "Street, bathroom. I don't care, do it!"

Ultimately, Lyndale's goal is to have students leave home for another home that they'll find at school.

"It's so important that we connect our school to home, home to school," Del said. "A home connection. Our children know that they are accepted as who they are."

Watch more local news:

Watch the latest local news from the Twin Cities in our YouTube playlist: