MINNEAPOLIS – The whistle from a light rail train can be heard in the distance. Cars zip past on Interstate 494, while passenger planes land and take off, seemingly within a stone’s throw.

Yet it is here, at Fort Snelling National Cemetery, that Ann Steffen finds her peace.

“It’s like a second home in a way,” Steffen says. “I’d just as soon sit here as in my own backyard.

Two or three times a week, Steffen can be found sitting in front of the gravestone of her husband Ronnie.

The former Marine died in 2016. Steffen sings to her husband and speaks in hushed tones of affection. “Oh, you sweetheart,” she says. “You are my love.”

She also admires her surroundings.

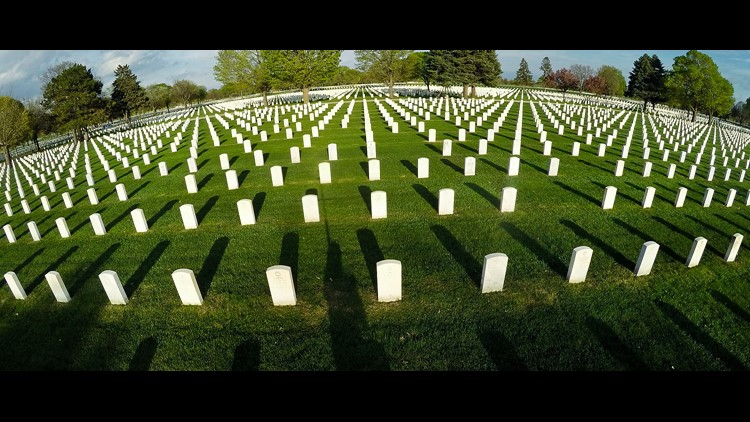

“Almost like a parade, with all the soldiers coming, all in formation,” Steffen says of the marble stones that surround her.

Were it a city, Fort Snelling National Cemetery would be Minnesota's third largest, more than two-and-a-half times the population of Duluth.

The cemetery is the final resting place for 228,000 service men and women, their spouses and dependent children.

Next year the cemetery will mark its 80th birthday.

“Our first burial in 1939 was a gentleman by the name of George Mallon. He was a medal of honor recipient from WWI,” says John Knapp, Deputy Director of Fort Snelling National Cemetery.

Farm fields surrounded the burial of Captain Mallon, with 436 empty acres of possibility.

“At the time, the newspaper articles billed it as the Arlington of the west,” Knapp says.

Among the cemetery’s early burials were soldiers' remains moved from old Fort Snelling.

Poor record keeping at the fort meant 280 service people arrived unknown, as noted on their stones in the oldest section of Fort Snelling National Cemetery.

But even those who arrived without names, earned a space all the riches in the world cannot buy.

“Bill Gates cannot be buried in this cemetery, because he didn't earn the right to be buried here,” Knapp says.

But Carolyn Kay Benjamin did, paid by the military service of her husband Larry.

Larry Benjamin is also a frequent visitor. A few days before Mother’s Day, he kneeled in front of his wife’s grave, praying and reflecting.

“Just being here gives you a sense of some peace or comfort,” Larry Benjamin says. “The quietness, the beauty of this area, even the birds or the animals you see out here, give you a sense of love for my wife.”

“Think of every one of these headstones as being a brick in a national shrine,” Knapp says.

The cemetery is a shrine dedicated to the dead, yet is also living and evolving, with 5,300 new arrivals each year – fourth most in the country among 135 national cemeteries.

“Nationally, veterans choose a national cemetery at about a 14- to 15-percent rate, but here in Minneapolis we were at 39 percent in 2017,” Knapp says.

He’s asked often if the cemetery might soon run out of space. There’s no immediate concern.

“We have enough space at this cemetery to take us out to the year 2060 and beyond,” Knapp says.

Fifty staff members care for the cemetery; 80 percent of them are veterans.

“It makes us very proud to be able to be part of something to help veterans and their families,” Knapp says.

Ann Steffen appreciates the effort, noting how well she’s treated on her trips to visit her husband.

“It's like a fraternity in a way,” she says, surveying the sea of gravestones. “It's a special place for special people.”