MINNEAPOLIS — Dr. H.M. Bracken faced a grave crisis during the fall of 1918.

The secretary of the Minnesota Board of Health watched helplessly as a mysterious virus tore through every corner of his state, filling up hospitals by the hundreds with patients reporting chills, fever, body pains and pneumonia-like symptoms.

Known erroneously at the time as the “Spanish Flu” – it had actually first appeared in Kansas – the influenza pandemic that perplexed Bracken and other state health officials would ultimately claim the lives of more than 10,000 people in Minnesota, at a time when the First World War had already inflicted its own toll.

Bracken, a well-known doctor in Minneapolis circles since at least the 1880s, emerged as the public face of Minnesota’s flu containment strategies in late 1918 and early 1919. On Oct. 12, 1918, just a few weeks after the state’s first reported case in the small community of Wells, Bracken wrote a letter to the public safety department in St. Paul with an urgent recommendation. “As epidemic influenza is prevailing throughout the country and is reaching Minnesota,” Bracken said, “I feel that as an initial step in controlling it we should prohibit all public gatherings which tend to bring groups of people together from various sections of the country, as political gatherings, conventions, church and school associations, etc.” Although Bracken did not advocate shutting down colleges or schools while in session, he did call for restrictions on entertainment venues like dance halls. “All of these gatherings,” Bracken wrote, “must be forbidden.”

Bracken would oversee Minnesota’s response through all three waves of the influenza pandemic, before eventually resigning from his Board of Health position in the spring of 1919 to take a federal job at the United States Public Health Service.

A century later, following the emergence of COVID-19, it is especially interesting to explore the state’s overall handling of the previous pandemic in 1918 and 1919. In Minnesota, state and city leaders differed widely in their approaches to the influenza virus, leading to a patchwork of rules that left many people confused. For example, Minneapolis shut down public spaces quicker than St. Paul, whereas the latter implemented a stricter system of quarantine that may have contributed to fewer people reporting influenza to physicians, according to researchers.

Although vastly different in many respects, a comparison of the 1918-19 pandemic response in Minnesota and the current response to COVID-19 reveals some fascinating parallels, ranging from recommendations on masks, sanitation measures, mass gatherings, sporting events, transportation and schools.

“If you were flung back in time 100 years,” Minnesota Historical Society research director Bill Convery said, “I think you’d be very surprised at the similarities.”

Masks: No 1918 Mandate in Minnesota

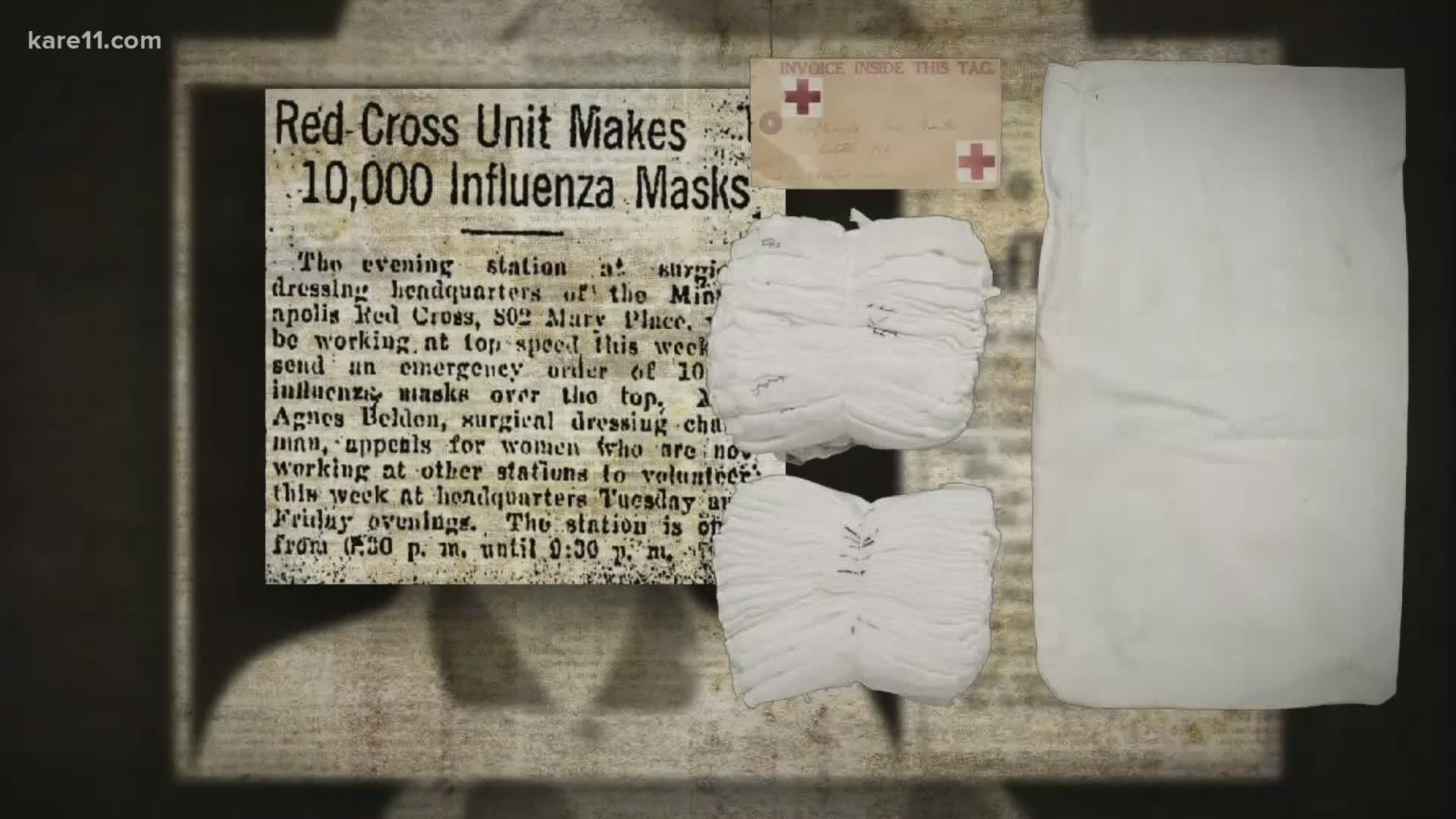

In October 1918, Dr. Bracken recommended that Minnesotans “wear a cheese cloth face mask over your mouth and nose.” With the Red Cross already pumping out thousands of gauze masks for doctors and at-risk patients, Bracken suggested that people build homemade face-coverings by cutting their own gauze into four nine-inch strips. “Every one can secure self-protection,” Bracken said, “by the simple procedure of wearing the mask.” Incredibly, despite his own recommendation, Bracken boldly proclaimed just a few weeks later that he did not wear a mask himself, saying he would “prefer to take my chances.”

Bracken’s contradiction underscores the mixed messaging that occurred during the flu pandemic in Minnesota, according to Miles Ott, a professor at Smith College who wrote an article for the Minnesota Department of Health nearly 15 years ago about the flu pandemic response in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

“There was this idea that wearing masks was a good idea,” Ott said, “but there wasn’t a message that everybody should wear masks.”

Unlike the Walz administration, Gov. Joseph A.A. Burnquist did not issue a statewide mask mandate, nor did the municipalities of Minneapolis or St. Paul. Newspaper archives indicate that a lot of people sported them anyway, including those who worked for the draft board in Minneapolis after the military handed down a mask requirement. In Winona, the local newspaper reported that “many are wearing ‘flu masks,’” adding that employees at the businesses and banks in town were especially careful to cover their faces.

In the absence of mask mandates, there is no evidence that Minnesotans staged any large-scale protests against their use. Bill Convery of the Minnesota Historical Society said that “mask-wearing seemed to be one of the more efficacious ways to prevent the virus from spreading. In general, Minnesotans tended to be more careful about things like mask-wearing in public.”

That was not the case, however, in other parts of the country, like the hard-hit area of California. In Berkeley, 35 citizens petitioned the city council to overturn its ban on face-coverings. “As voters, we, the undersigned, do hereby protest against the wearing of masks," the petitioners wrote, “because they are unsanitary.” The public health commissioner called the efforts “foolish.”

Sanitation and Public Health

Just as health officials initiated “Stay Safe MN” in 2020, the state and federal governments launched an aggressive public health campaign in the fall of 1918 to educate people about the spread of influenza. “Washing your hands, avoiding contact with other people, maintaining social distancing,” Convery said, “all of these were recommendations that public health officials made.”

According to documents preserved by MNopedia and the Minnesota Historical Society, various campaigns advocated to “keep the mouth and teeth clean,” “get fresh air,” “cover your mouth when you cough and sneeze,” and “avoid crowds.”

The “fresh air” recommendation was particularly important, according to Convery.

“Doctors at the time felt fresh air and being outdoors was one of the best preventative measures,” he said, “that encouraged people to keep their windows open, or in crowded offices, to close windows.”

Ott’s research found that Minneapolis and St. Paul both mandated streetcars to keep their windows open, in order to allow for more fresh air in the warm months. St. Paul even went so far as restricting elevator use in buildings under six stories, so that people wouldn’t spend as much time in confined spaces. Protests from hotel managers led to some adjustments to those rules, Ott said.

Public Gatherings and Sporting Events

Just as COVID-19 forced the public to cancel most of their social plans, the influenza pandemic also led to a shutdown of daily life on an unthinkable scale.

On October 11, 1918, the city of Minneapolis closed “churches, schools, theaters, motion picture shows, dance halls,” and pool halls. Just one day earlier, the city had tallied an alarming 424 new cases of influenza. “Officials can call on any police power in the state,” the Minneapolis Tribune reported, “to insure [enforcement] of the order.”

Just three days later, with “no other amusement of any kind,” thousands of restless Minnesotans challenged the city’s order by attending a series of amateur football games. Public health officials did not take kindly to the disobedience. “As soon as crowds gathered,” the Tribune reported, “the police dispersed them, but not without difficulty.”

Unfortunately, the fans would have to live without football temporarily. The University of Minnesota, a powerhouse football program at the time under a practicing physician and coach named Dr. Henry L. Williams, played an October 19 exhibition game against “Overland Aviation” with no general admittance to Northrop Field. Fielding a team made up of Student Army Training Corps members during the First World War, the Gophers claimed a 30-0 victory in front of 5,000 fans – consisting exclusively of students and military members.

The Tribune reported that the University of Minnesota lost “several thousand dollars because the public was not admitted to yesterday’s game. Another spectator-less game would be a financial blow that would take Minnesota some time to recover from.” The Gophers played in front of very small crowds for the next several weeks, until Minneapolis lifted its influenza ban on November 15 – the day before Minnesota hosted arch rival Wisconsin. People instantly flocked to Northrop Field, as well as theaters, pool halls, and other venues of entertainment.

“Minneapolis enjoyed the first long, hearty laugh, and the first sobby weeps – or weepy sobs – it has had for a month, yesterday afternoon,” the Tribune wrote the next day. “Sure, the movies were opened!”

Although Minneapolis spent a large portion of October on lockdown, the city of St. Paul did not enact a shutdown order until November 6. The order closed “churches, schools, theaters, saloons, soda fountains, billiard and pool halls, bowling alleys and other public meeting places.”

Lessons to Learn

In his research, Bill Convery found that the saloon closures were especially difficult for people to accept – and they often found ways around those orders.

“A lot of people ignored that and went and had drinks anyway,” Convery said. “It was the heyday before the beginning of Prohibition and people felt like the clock was ticking.”

Other than some isolated incidents, like illegal bar-hopping and football-watching, it does not appear there was any organized opposition to public health measures during the 1918-1919 flu pandemic in Minnesota.

But there are lessons to learn.

“I would say, that our big summary at the end of the paper, was that we need plans in place, in advance,” Miles Ott said. “There needs to be agreement between government organizations about how they’re going to work with each other and clear communication to the public about why things are happening.”

In particular, he pointed to Dr. Bracken’s conflicting ideas about masks, when the state’s top health official demanded everyone else wear them but wouldn’t do so himself.

“And that,” Ott said, “just opened the door for contradictions everywhere else.”

Sources:

General information on Minnesota death toll, dates, flu response, etc.: Mary Laine, “Influenza Epidemic in Minnesota, 1918,” MNopedia and the Minnesota Historical Society, first published January 18, 2019, accessed digitally via: https://www.mnopedia.org/event/influenza-epidemic-minnesota-1918

Ott’s research from 2006-07: Ott, Miles et al. “Lessons learned from the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota.” Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974) vol. 122,6 (2007): 803-10. doi:10.1177/003335490712200612

Bracken letter, “must be forbidden”: Letter, To: Commission of Public Safety, From: H.M. Bracken, Public Safety Commission, Main Files, “Influenza Enyclopedia,” University of Michigan, October 12, 1918, accessed via: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/idx/f/flu/7950flu.0015.597/1/--letter-to-commission-of-public-safety-from-h-m-bracken?rgn=subject;view=image;q1=Minnesota+Commission+of+Public+Safety

Mask recommendation and “simple procedure of wearing the mask”: “Wear Cheese Cloth Mask,” Winona Republican-Herald, October 17, 1918, Page 2.

“take my chances” and quote from Bracken: The quote is cited in Ott’s paper, but also referenced in “Health and Happiness,” Dr. P.M. Hall, Minneapolis Tribune, November 19, 1918, Page 8.

“many are wearing ‘flu masks’”: “City News,” Winona Republican-Herald, October 30, 1918, Page 3.

“foolish” and Berkeley petition: “Berkeleyans Protest Flu Masks,” Oakland Tribune, November 6, 1918, Page 9.

“of the order”: “City Closed to End Wave of Influenza,” Minneapolis Tribune, October 12, 1918, Page 1.

“not without difficulty”: ‘Flu’ Order Stops Park Grid Games, Minneapolis Tribune, October 14, 1918, Page 12.

“not admitted to yesterday’s game”: “Sports Fans Hope For End of Closing Ban,” Minneapolis Tribune, October 20, 1918, Page 22.

Information on Gopher game against Overland: “Gophers Win First Practice Game From Overland Team, 30 to 0,” Minneapolis Tribune, October 20, 1918, Page 22.

“movies were opened!”: “City Laughs Once More As Movies Open,” Minneapolis Tribune, November 16, 1918, Page 1.

St. Paul order: “St. Paul Closes Tight to Check Influenza,” Minneapolis Tribune, November 5, 1918, Page 11.