As the first shipment of Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine arrived in Minnesota to a waiting Gov. Tim Walz, Dr. Renee Crichlow took a quick lunch break from the last of her 7-day stretch tending to COVID-19 patients at North Memorial hospital.

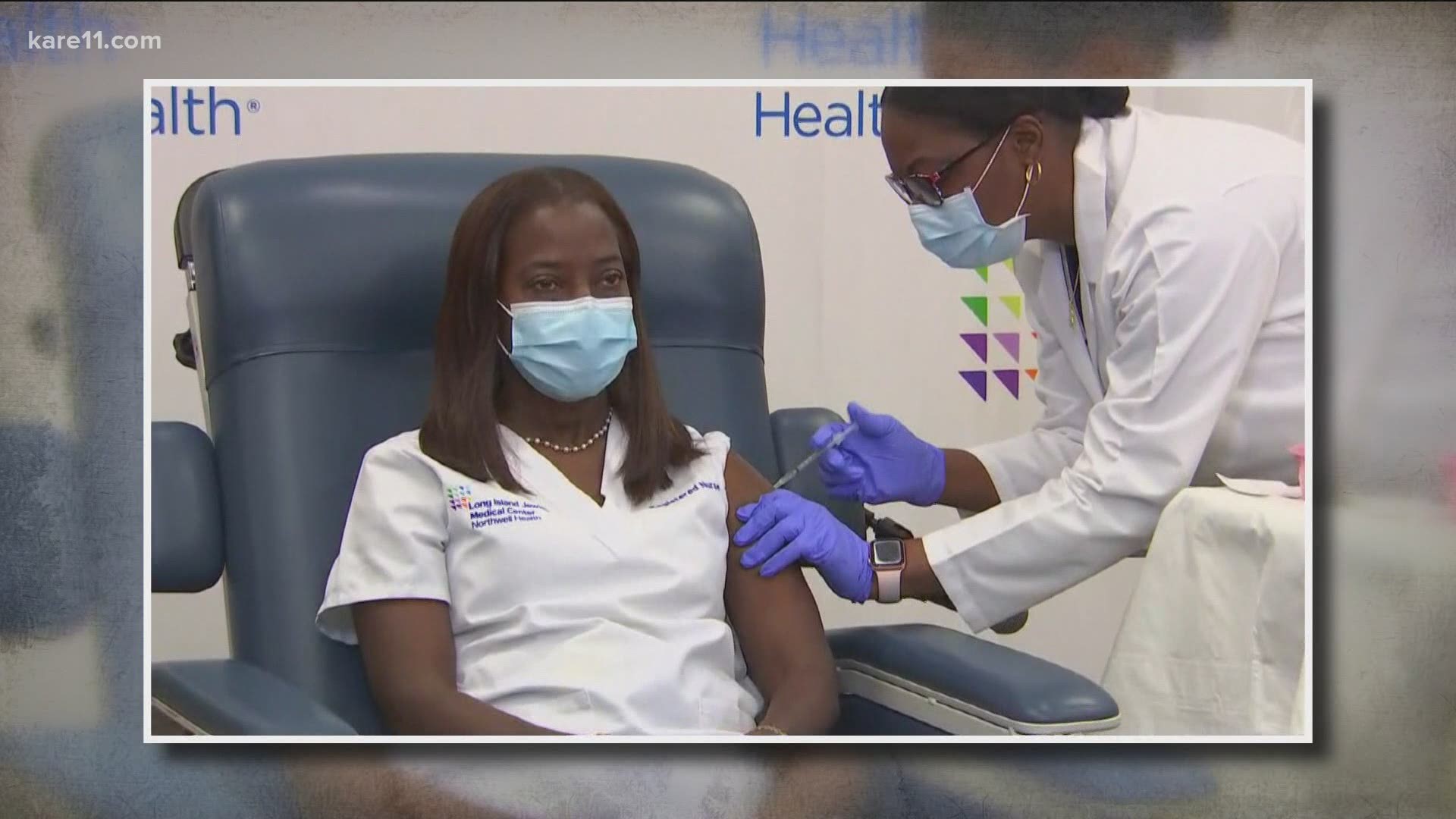

She caught the footage of the historic turning point in the fight against coronavirus, as a New York ICU nurse was among the first in the country to receive the new vaccine.

“It's awesome. It’s really powerful,” said Dr. Crichlow, who also practices and teaches family medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School. “None of us want to live in this fear anymore. And sometimes to get through fear, we have to find our own courage, and we find it best together.”

Dr. Crichlow once thought this momentous breakthrough could be years in the making, according to traditional vaccine development models.

“The good news is what happened now is they're not using traditional methods. The mRNA vaccines are very innovative,” she said. “The idea of taking a small coded sample that of something that we have in our body anyway, we all have RNA in our body. It’s basically a little recipe, your body is left with immunity.”

The mRNA technology in this Pfizer vaccine and the upcoming Moderna vaccine teaches our cells how to make a what's called a "spike protein" found on the surface of COVID-19 virus, and that triggers an immune response. Dr. Crichlow said thanks to this new innovation combined with thousands of heroic volunteers that participated in vaccine trials, the science was able to scale up in a revolutionary way. She plans to get the vaccine as soon as she possibly can.

“As an African American physician, it's my responsibility, I believe, to get the shot and get it in a way that people can see it. And say, you know, ‘this is something I will do, this is something I will do for my family,’” said Dr. Crichlow. “It’s definitely something I trust and I believe it’s safe.”

She also understands many of her patients will be skeptical of the new vaccine and believes it’s a doctor’s duty not just to set an example but begin a dialogue about those fears.

“It behooves all of us to understand that these concerns are real, and they're valid. But we also need to understand that we have an opportunity now to start some healing,” said Dr. Crichlow. “There are entire communities, especially African American communities, and communities of color that have been abused by a long-term racist, structural racist community of medicine.”

Dr. Crichlow believes the burden is on the medical community itself---not patients or communities--to address vaccine fears and build public trust. She points to the involvement of communities of colors into the development of vaccine, including a Black virologist key to the innovation.

“We need to show them, it's something we're willing to put into our own bodies, even before we put it into theirs. We want to show them that safe. What would you do to save your grandmother?” said Dr. Crichlow. “I would take a shot. What would you do to save your children and all of your loved ones? I'll take that shot. It’s our best shot right now,” she concluded.