The Bataan Death March and the disappearance of Minnesota native Julius St. John Knudsen

Julius St. John Knudsen is the only Minnesota native still missing in action from WWII's Bataan Death March. But his family won't give up on the 80-year search.

The Disappearance of Julius St. John Knudsen

When American and Filipino forces surrendered in the Philippines on April 9, 1942, just months into Japan’s invasion of the islands, Technician Fifth Class Julius St. John Knudsen of the 194th Tank Battalion, Company A, laid down his arms and prepared for the worst.

Knudsen, a 25-year-old from central Minnesota, never recorded what he thought or felt in those early days of World War II, as he participated in the largest surrender in U.S. history at the Bataan Peninsula, but the situation had turned desperate. Allied troops, backed into a corner and heavily outnumbered, started destroying their own tanks to prevent the enemy from using the equipment against them. Running dangerously low on food, water and gasoline, they knew there was no help on the way. The U.S. Navy, after all, had no ability to launch a rescue mission across the Pacific, not after the decimation of the fleet at Pearl Harbor.

Soon enough, Knudsen and tens of thousands of other American and Filipino soldiers would begin the infamous Bataan Death March, as Japanese soldiers transferred them to prisoner-of-war camps in sweltering conditions across a roughly 60-mile stretch of the Philippines. Although estimates vary, as many as 10,000 Allied soldiers – overwhelmingly Filipino – may have died along the way, either shot to death, diseased or starved.

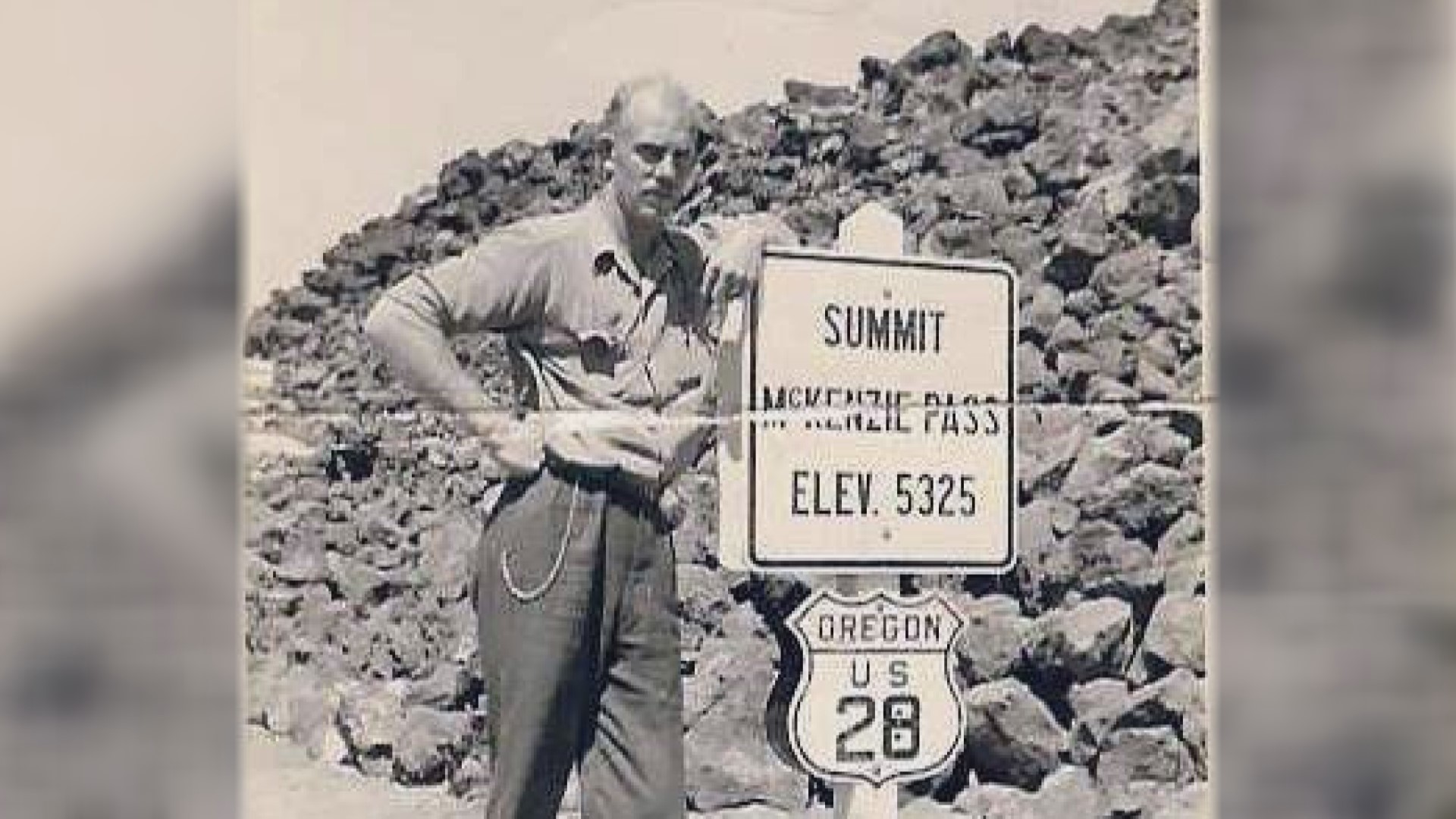

Knudsen, just a few years removed from driving trucks in California during the Depression, undoubtedly made that death march – a portion of it, at least. His fate, even eighty years later, remains unknown. In notes discovered from a bunker after the war, unit commander Col. Ernest B. Miller wrote that Knudsen was “last seen at Lubao,” a town along the march route.

To this day, Knudsen’s body has never been found, and his family still has no idea what happened to him in the spring of 1942. Of the 64 men in the 194th Tank Battalion who left Brainerd with Company A the previous year, about half died at the Philippines, while the other half returned home to Minnesota.

Yet, only one of those Brainerd soldiers – Julius St. John Knudsen – remains officially classified as missing in action (MIA).

The furious search for his whereabouts has now lasted eight decades.

Based on recent revelations and years of personal research, nephew Jim Knudsen believes Julius’ remains were reburied anonymously in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, along with countless other missing service members.

“They don’t know who any of them are, but they’re somebody,” Jim said. “And one of those is my uncle.”

Eighty Years of Mystery

On the 80th anniversary of the American surrender at Bataan – April 9, 2022 – Jim Knudsen accepted a Congressional Gold Medal on behalf of his uncle at a Saturday afternoon ceremony in Brainerd. Standing on stage at the newly renovated Armory, underneath the words Bataan Memorial Hall, Jim addressed the crowd with a tone of gratitude and optimism.

“This medal belongs to Julius, but our family will now guard and cherish it,” Jim said, “as we await his return home.”

Two Congressional Gold Medals were awarded posthumously that day to members of the 194th Tank Battalion – to Julius St. John Knudsen, MIA, and Herbert Strobel, who was confirmed to be killed in action in the Philippines in late December 1941. Although they never returned home to their families in Minnesota, their legacy has not been forgotten in Brainerd, which holds a ceremony every year in April to honor the community’s local connection to Bataan.

Sonny Busa of the Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project, a former U.S. diplomat whose parents fought the Japanese during the occupation of the Philippines, traveled from the East Coast to Brainerd to serve as a special guest during the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony and spoke highly of his first visit to the state of Minnesota. Emphasizing the collaboration between Filipino and American soldiers during World War II, he remains committed to preserving the history of the Bataan Death March, despite the episode serving as one of the darker points of the Allied effort in World War II.

“These were Americans who fought. These were boys who came from the farms and factories here in Minnesota,” Busa said. “These were Brainerd boys. These were Baxter boys. These were northern Minnesota boys, who went halfway around the world to defend freedom. A lot of them had never heard of the Philippines.”

That may have been the case for Julius St. John Knudsen.

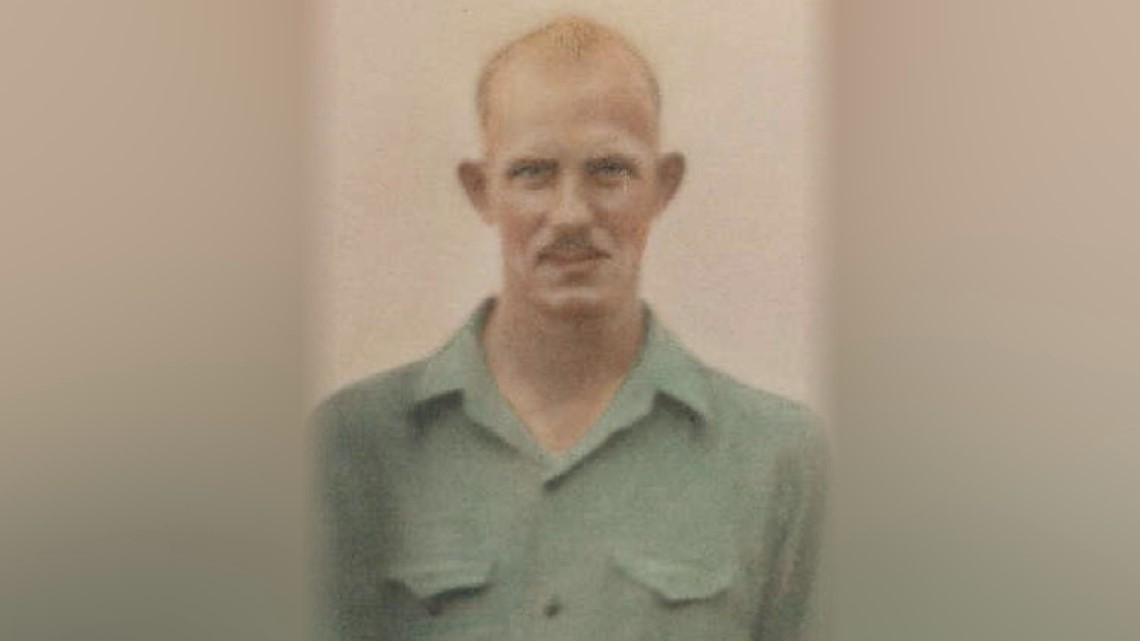

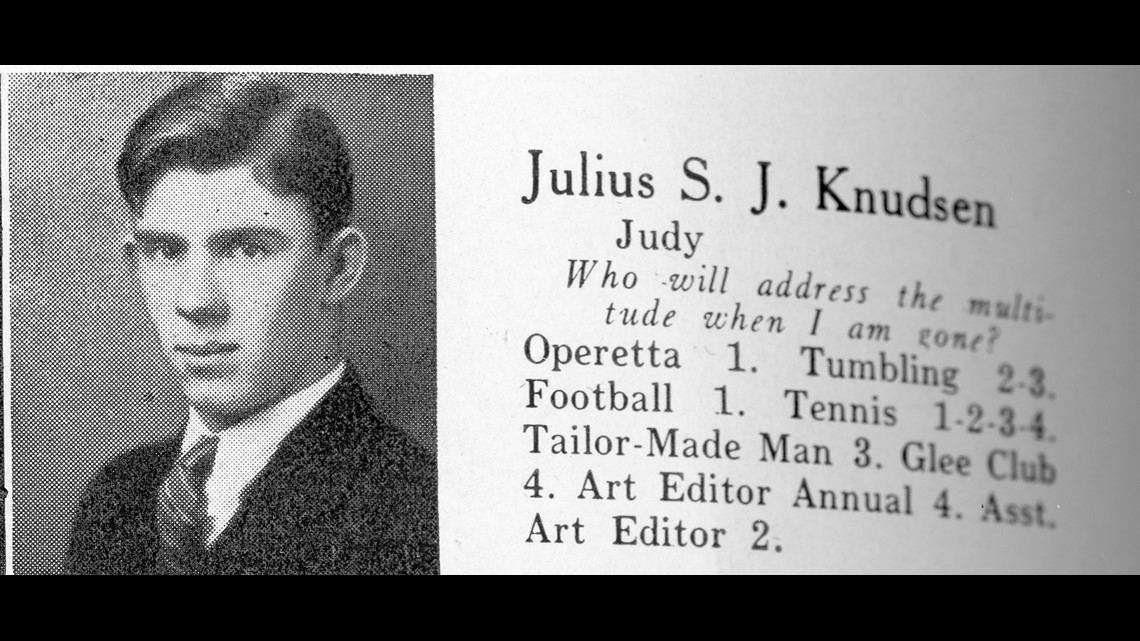

Born in 1916, he and his two younger brothers grew up in Brainerd, at the time a town of about 10,000 on the Mississippi River. In their early years, the three Knudsen boys spent many summers helping their father Louis with his duties as the county surveyor, until the Depression put just about everybody out of work.

Julius, known to family by the nickname Judy, carried a fierce independent streak as the oldest son. Recalling stories that his father, Wilbur, passed through generations, nephew Jim Knudsen said Julius might be known these days as a “hothead.” But he was a loyal friend, too, with a sense of adventure, which is how he ended up in California in the late 1930s driving trucks. Having moved to the West Coast to find work during the Depression, Julius lived at a hotel in Los Angeles until World War II broke out in Europe in 1939 following Hitler’s invasion of Poland.

While the U.S. initially pledged neutrality, Congress approved a historic peacetime draft measure in 1940, forcing millions of young men to sign up for Selective Service to prepare for possible American involvement in the war. On his draft registration card, dated Oct. 1940, Julius St. John Knudsen listed 1221 S. Main Street in Los Angeles as his address, estimating his height and weight at 6-foot-2½ and 186 pounds.

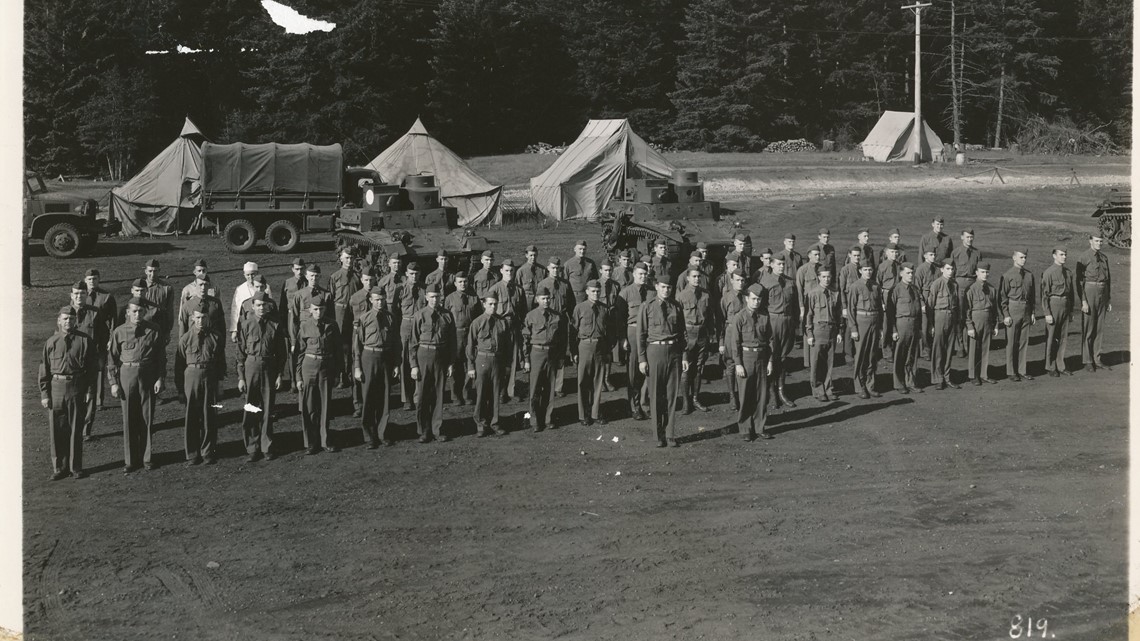

Despite having eligibility for the draft, it appears Julius enlisted voluntarily in the military in March 1941. Along with a friend named Robert Doerck, he joined a California-based regiment and reported to Fort Lewis, Washington, for training in the Pacific Northwest. By pure coincidence, the 194th Tank Battalion – with Company A from Julius’ hometown of Brainerd – had also arrived for training in Fort Lewis after being federalized that winter.

“They said, ‘I want to be with my hometown buddies,’” Jim Knudsen said. “His friend Robert said, ‘I’ll go with you.’ Those two joined and off they went. That was the beginning of their travels to the Philippines.”

More than 60 members of the 194th Tank Battalion Company A, originating from Brainerd, sailed to the Philippines in September 1941, marking the first U.S. armored unit in the Pacific during the conflict later to be known as World War II.

The Philippines, an American territory at the time, appeared to be an increasingly vulnerable target to Japanese aggression in the Pacific. That summer, Japan had inched closer to Allied territories by occupying Southern French Indochina, leading the Roosevelt administration to respond with harsh economic sanctions. Given this tension, more U.S. troops shipped overseas in the fall of 1941 to reinforce the Philippines, where they would assist thousands of Filipino soldiers who fought as a part of the American military. The 194th Tank Battalion pledged to defend Clark Field, a U.S. base located an hour and a half north of the capital city Manila.

Julius St. John Knudsen did not visit Brainerd prior to departing for the Philippines, and given his move in the 1930s to California, it is likely his family might not have seen him in years. He also did not write many letters home, meaning he left behind very little evidence of his time on the islands.

However, in November 1941, his parents Bessie and Louis took advantage of novel recording technology at the local Armory in Brainerd and created audio messages to send to Julius. Families of the 194th Tank Battalion in Brainerd were shocked to learn they could communicate with their sons in the Pacific, thousands of miles away, without having to write a letter.

“Hello, Judy, this is mother. I want you to know that this was Dad’s idea, and it has just taken the town by storm,” Bessie recorded in her audio message, hoping it would arrive in the Philippines in time for the holidays. “I’m going to wish you a Merry Christmas now, Judy. Goodbye.”

Julius’ father, Louis, took a sterner tone, but offered words of wisdom for his son while he was stationed in the tropical Philippines.

“Hello, Julius, this is your dad. I want to wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. We’re all busy here at home,” Louis said. “I hope that you aren’t getting too much heat. We know that you’re in the other end of the world and that you’re having your summer now. But, do what you can fella, and I wish you a Merry Christmas again and I hope you get along in good shape. Write soon.”

It may have been one of Bessie and Louis’ last attempts at correspondence with their son. Unfortunately, the messages never reached Julius, because soon the 194th Tank Battalion would become preoccupied with the fight of their lives.

Hours after bombing Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Japan attacked the Philippines and Clark Field, commencing an invasion that would lead to the surrender of the American and Filipino troops just four months later in April 1942. Despite a valiant effort, these Allied troops ultimately retreated to the Bataan Peninsula, where many were sick, hungry, low on vital supplies, and now prisoners of war under Japanese occupation.

So began the Bataan Death March – the last time anyone ever saw Julius St. John Knudsen alive.

The March

Having seized control of the Philippines in the spring of 1942, Japanese military leaders marched tens of thousands of American and Filipino prisoners of war for days in brutal April heat, heading first to Camp O’Donnell and later the Cabanatuan prison camp. “The Bataan Death March,” the National World War II Museum in New Orleans writes, “is remembered as an absolute tragedy.” The route started at the southern end of the Bataan peninsula, winding north past Manila Bay deeper into the mainland. The Americans and Filipinos had very little food or water, with many succumbing to malnutrition, malaria and dysentery. In his notes, Col. Miller recorded that some of his men from the 194th Tank Battalion were “shot on detail” by Japanese troops, or subject to “burial alive.”

Survivors feared they would not last long on the march to the prison camps. Walt Straka, a Brainerd native who lived to the age of 101, said decades later that the “death march and Camp O’Donnell were two of the darkest spots of the whole thing… I had no doubt we were going to die. In my mind, I knew it was over.”

The death march spanned several days but did not follow one single, organized line, making it difficult for the U.S. military to trace the whereabouts of every soldier – including Julius St. John Knudsen.

“Technician Fifth Class Knudsen’s fate became hazy at this point,” according to an official U.S. Department of Defense document shared with the Knudsen family, “but it appears as if he participated on this long march.” The details of his disappearance, however, remain entirely unclear, “with little that can be said with any certainty.” Mysteriously, the army provided June 30, 1942, as the date of Knudsen’s death at the Cabanatuan prison camp, but no cause of death has ever been provided and the National Archives death records from Cabanatuan do not include his name. Knudsen also does not appear on any POW camp rosters.

“It is conceivable that Tec 5 Knudsen perished in either April or May 1942, on the sixty-mile march from Bataan to Camp O’Donnell,” the Department of Defense has written, leaving open the possibility that Knudsen also might have died in transit “from one camp to another.” In summary, “the true reason for why Tec 5 Knudsen does not appear on any Cabanatuan or Camp O’Donnell records, or when and where he died, remains a mystery.”

Nephew Jim Knudsen is determined to solve the mystery of his father Wilbur’s brother.

“Before my dad died 13 years ago, I promised him I would keep up the search for Julius,” Jim said. “And I have.”

While he was still alive, Wilbur Knudsen – known as “Yibby” – told the Brainerd Dispatch in 2005 he believed his defiant older brother Julius may have “challenged one of the Japanese guards and was killed as a result of his actions.” Yibby also said at the time that two other prisoners of war from Bataan “recalled seeing his brother on the march but they lost track of him.”

Jim Opolony, one of the nation’s top chroniclers of the Bataan Death March, has written about “conflicting information” regarding Julius St. John Knudsen’s disappearance. On his website, Opolony lists several potential theories based on various sources, including that Knudsen might have been shot near Balanga, an account provided by fellow 194th Tank Battalion member Walt Straka.

Clearly, the evidence is not definitive.

With the help of the Internet and private researchers, however, Knudsen has uncovered some illuminating pieces of information in recent years, providing groundbreaking insight into Julius’ disappearance in the Philippines. The most significant development was Jim’s discovery of Col. Miller’s notes. Accidentally misspelling Knudsen’s name, Col. Miller listed the following: Pvt. Knudson, Julius-Last seen at Lubao. That town, Lubao, is located midway between the southern tip of Bataan and Camp O’Donnell.

In other words, Col. Miller’s notes seem to confirm that Julius St. John Knudsen may have died during the death march, rather than at a prisoner-of-war camp. In another twist, Knudsen’s name appears next to Pvt. Robert Doerck, who Col. Miller also wrote had been “last seen at Lubao.” That name was not familiar to the Knudsen family until a private researcher in Colorado discovered that Doerck hailed from Southern California and had a serial number very close to Julius St. John Knudsen. To Jim Knudsen, that evidence indicates that his uncle and Doerck were friends and must have signed up for the service at nearly the same time in Los Angeles back in 1941.

“They joined the 194th as buddies, so all this buddy talk gets in your mind and drives the direction of where you want to go. And, ‘what would happen if that was me and one of my friends?’ I’d be with them until the end,” Jim Knudsen said. “We have to presume, at this point, they were both killed near Lubao.”

But there’s only one way to find out for sure.

“DNA,” Jim Knudsen says. “You’re never going to figure it out otherwise.”

The Search Continues

In late April, a few weeks after the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony for his uncle, Jim Knudsen met with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), which coincidentally happened to hold an in-person update in Brooklyn Park for family of unaccounted service members. The meeting was productive. According to Jim, he spoke with a historian for about 30 minutes, and it appears his uncle’s name may be on a list of 152 people killed between Balanga and San Fernando but reburied in Manila – with the geographical area squaring precisely with Col. Miller’s notes suggesting Julius disappeared at Lubao.

While the Knudsen family has submitted DNA samples to the federal government in hopes of identifying Julius, the DPAA cannot request a disinterment of graves until it obtains a certain percentage of DNA samples in a candidate list. Knudsen said he’s now working to find as many relatives as possible from the 152 service members thought to have gone missing between Balanga and San Fernando, so that the process can move forward to dig up graves and identify bones.

The DPAA and other partner agencies have an enormous task, with more than 81,600 American service members still considered missing from conflicts dating back to World War II. In the Pacific specifically during World War II, the agency estimates that 46,680 remain missing – the largest such group in any area of the world.

But all hope is not lost.

So far in 2022, the DPAA has identified 60 missing service members from World War II, and even families in Minnesota have received closure in recent years. Surviving relatives of Navy Fireman Neal Kenneth Todd, for example, celebrated the return of his remains last year at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport after his death aboard the USS Oklahoma at Pearl Harbor was finally confirmed.

Jim Knudsen dreams of the day he can welcome Uncle Julius home.

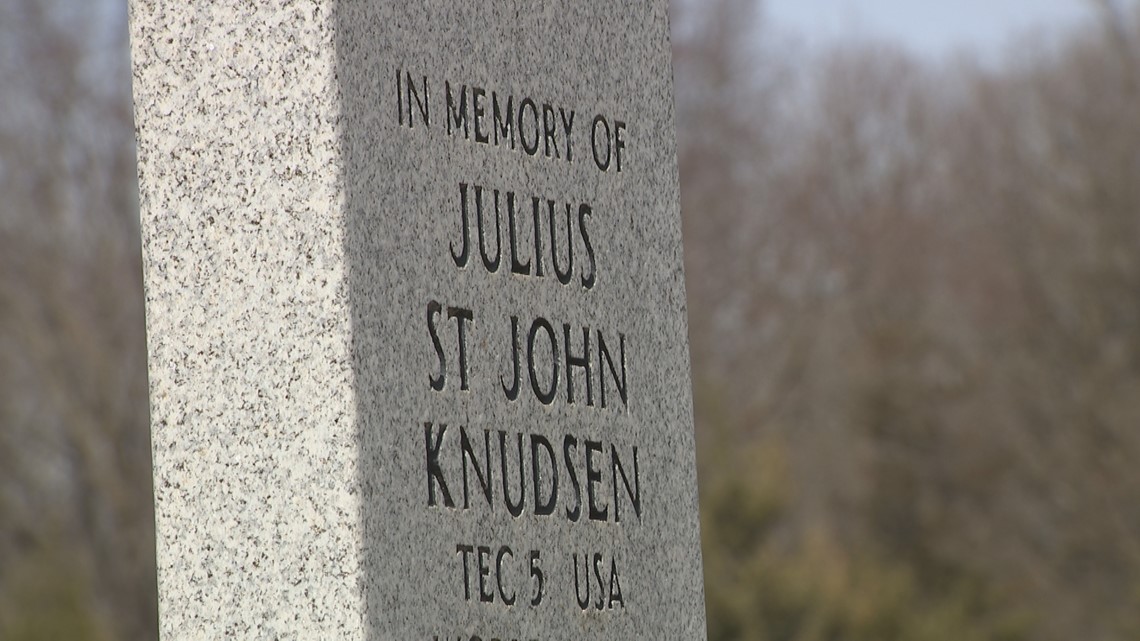

Already, the family has secured a headstone at the Minnesota State Veterans Cemetery near Camp Ripley in Little Falls, in anticipation of a positive identification on Julius St. John Knudsen’s remains in the Philippines.

“If they find my uncle and bring him home, there’s going to be a hearse on the highway and people on the overpasses with flags,” Jim said. “I can just envision what would happen.”