Minnesota was a part of the Union, right? One of the first states to join.

But that doesn't mean that the North Star State was free from the practice of slavery. In fact, slavery was legal at different times and in different ways in Minnesota. At one point, there was even a movement to change the law to legalize it - at least for southern tourists.

Dr. Christopher Lehman, the chair of the Department of Ethnic, Gender and Women's Studies at St. Cloud State University, has spent years researching the topic of slavery's impact in the Midwest. His latest book, "Slavery's Reach," dives into how Minnesota benefited from the money of slaveholders, both directly and indirectly, and how slavery persisted even in the north.

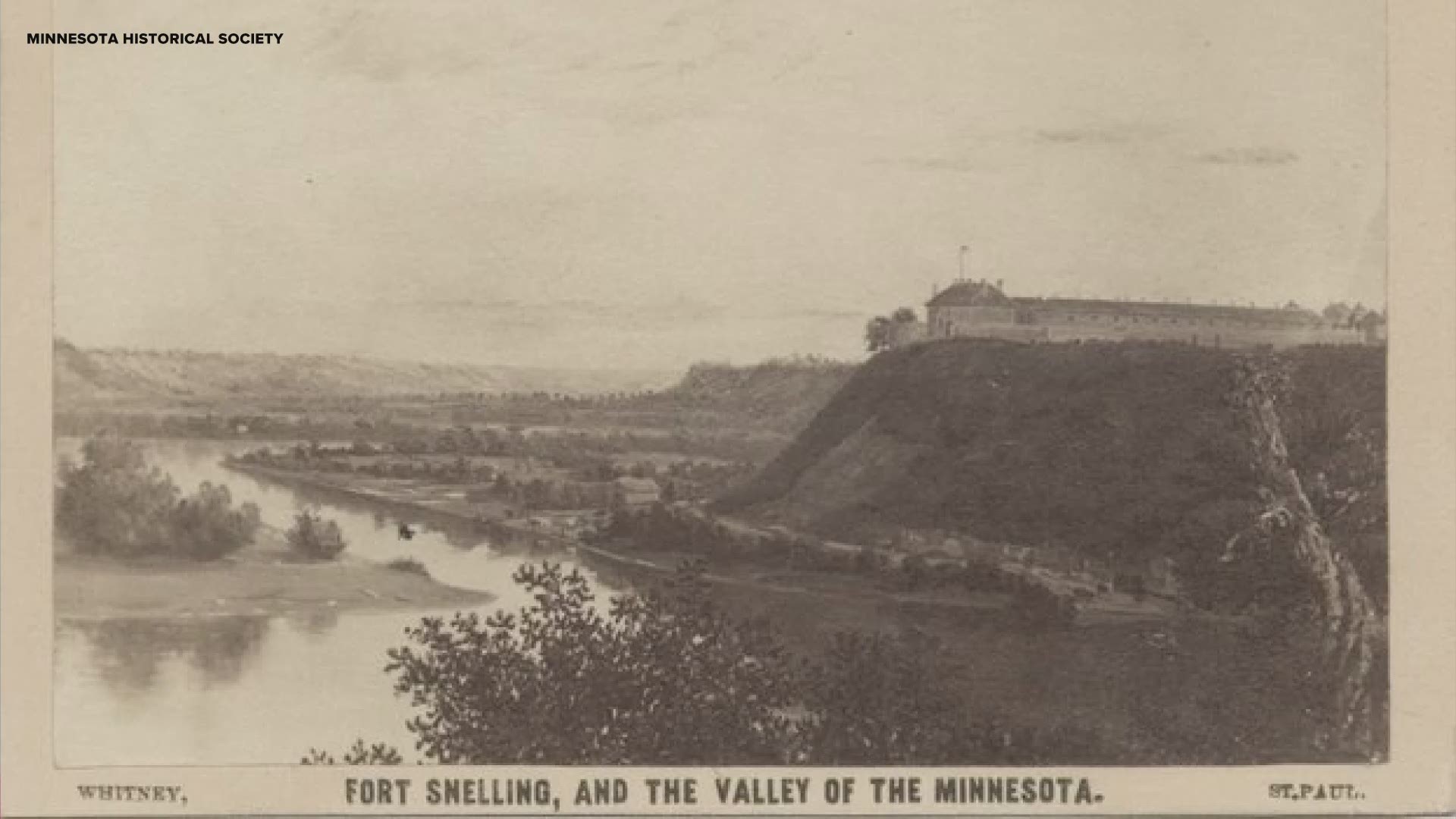

Fur trading and military bases

Slavery existed in Minnesota even before its organization as a territory in 1849.

As early as 1820, when Fort Snelling was established in the unincorporated territory of Minnesota, there was government-sanctioned slavery on the base.

"Even though there were a couple of federal laws in place in the 1820s, the government still told military officers from the south, 'You can take a slave with you and that’ll be OK, and we’ll even give you a stipend to help take care of that slave,'" Lehman said.

Over the years before Minnesota became a territory, one of the major fur trading companies operating there, American Fur, was owned by three St. Louis slaveholders. When fur trading died out, the same company continued to dominate Minnesota's real estate market. Many of Minnesota's "founding fathers" worked for these slaveholders, including John Prince, the founder of Princeton, Minnesota, and Henry Sibley, Minnesota's first governor.

In 1853, Joseph Travis Rosser was appointed Minnesota's territorial secretary, effectively the lieutenant governor. Rosser, a slaveholder from Virginia, held the post for four years. There's no evidence that he held slaves in Minnesota - but there's also no evidence that he sold any of his slaves once he got the job.

"That’s one of the things that surprised me, was that there were still these concrete connections between slaveholders and Minnesotans, and money being transferred between the two," Lehman said.

Tourism and visiting southerners

In 1854, the new technology of the steamboat made it easier for people in the south to head up to Minnesota for a spring or summer vacation. According to Lehman's research, the state of Minnesota "generally (turned) a blind eye" to the slavery that accompanied these visitors.

"They don’t make people who bring slaves to Minnesota free them," Lehman said. "Because they figure number one, that they’ll just go back to the south when the summer’s over anyway. And number two, they really wanna have those tourism dollars."

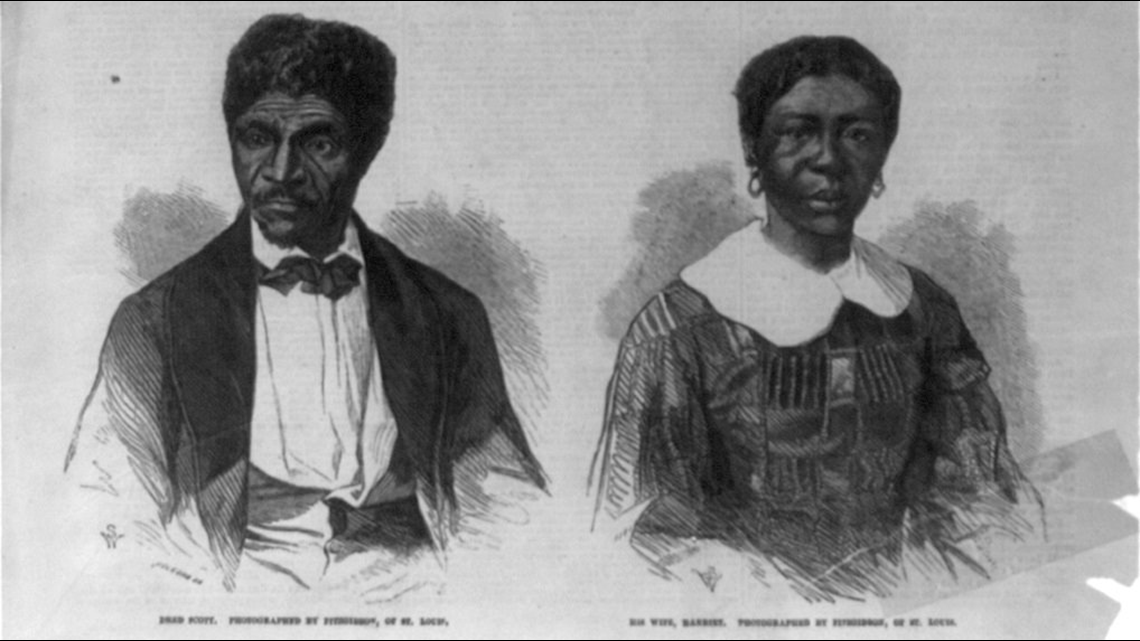

14 months of slavery

For a long 14 months in Minnesota, slavery was actually and officially legal.

This period dates back to the infamous Supreme Court ruling known as the Dred Scott decision. The court said that a slaveholder can take a slave to any territory, north or south, and not have to free them.

"Minnesota’s not a state yet, so for 14 months slavery is legal in Minnesota," Lehman said. "And that actually causes an influx of tourists in the summer of 1857, because now they know for sure that nothing’s going to happen to their slaves in Minnesota, because it’s perfect legal."

Lehman found that after Minnesota became a free state in 1858, tourism leaders again turned a blind eye to this practice in order to keep business going.

The movement to make Minnesota a slave state

Slavery's reach in Minnesota wasn't over once it became a "free state" in 1858.

In fact, there was a political movement to legalize some slavery in order to protect tourism.

In 1860, Minnesota had just elected a Republican governor. Because the Republican party opposed slavery, Lehman said southerners were worried that if they continued visiting, their slaves would be emancipated.

A movement began to make slavery legal, just for southern tourists.

"It was a mix of politicians and business people who stood to lose a lot of money if the slaveholders didn’t come back," Lehman said.

Six hundred residents of Stillwater, St. Anthony and St. Paul signed a petition.

A proposal went to the state legislature, but failed. The vote was 29-5 in the Senate, and 51-18 in the House.

"The votes weren’t even close - but they were not unanimous," Lehman said. "There were some people in Minnesota’s legislature who voted to make Minnesota a slave state, and primarily they were the people who had been making money by doing business with the slave holders."

One of the "yes" votes came from George Sweet, known as one of the founders of Sauk Rapids.

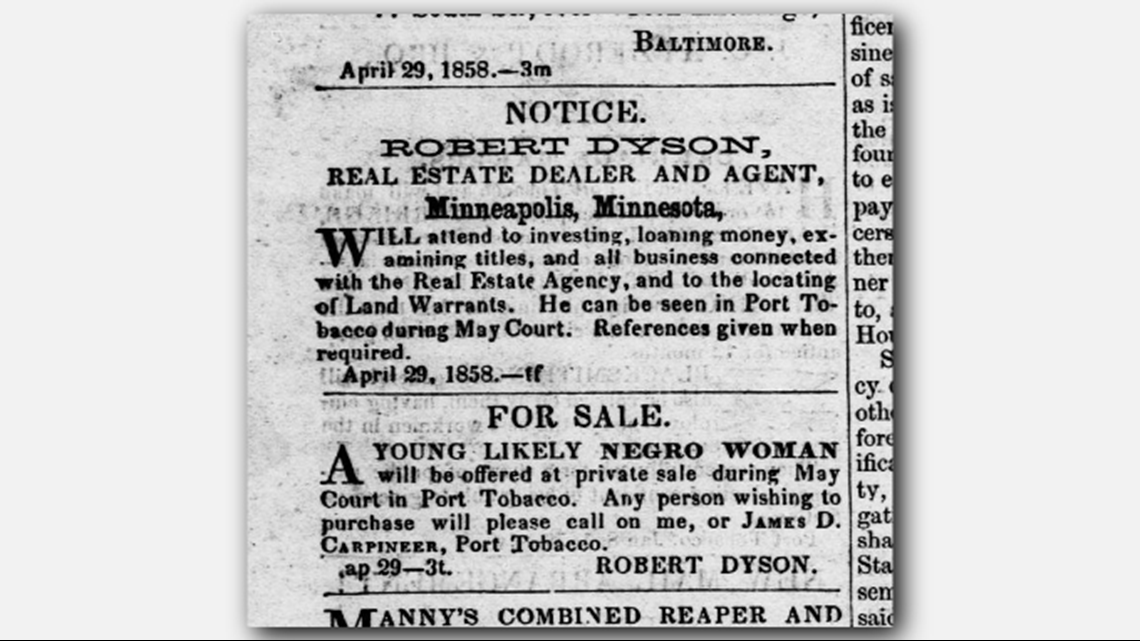

Follow the money

In his books and in his classes, Lehman said he tries to educate people about the ways in which Minnesota was complicit in the slave economy.

"This was not something that Minnesotans did accidentally, or at least the most powerful Minnesotans," Lehman said.

He points to a newspaper ad in Maryland, printed in 1858. It is by a Robert Dyson, who is advertising his business office in Minneapolis. The ad below it, by the same Robert Dyson, announces that he has a woman he would like to sell in Maryland.

Warning: The image below contains offensive language.

"For some people in Minnesota, it was enough that they weren’t active slaveholders themselves, but just doing business with them, and they can always tell themselves, 'Well, I’m not buying anybody, I’m not whipping anybody - I’m just taking money from people who do,'" Lehman said.

In Belle Plaine and Shakopee, families from the south bought up almost the entire town, Lehman said. In both cases, they did so with money made by selling all their slaves in the south.

"That actually does matter, where the money comes from, because it ties Minnesota to the institution of slavery and to the economy of slavery," Lehman said.