ST. PAUL - On the night Jean Krause was sexually assaulted by a worker at Heritage House Assisted Living, she was helpless.

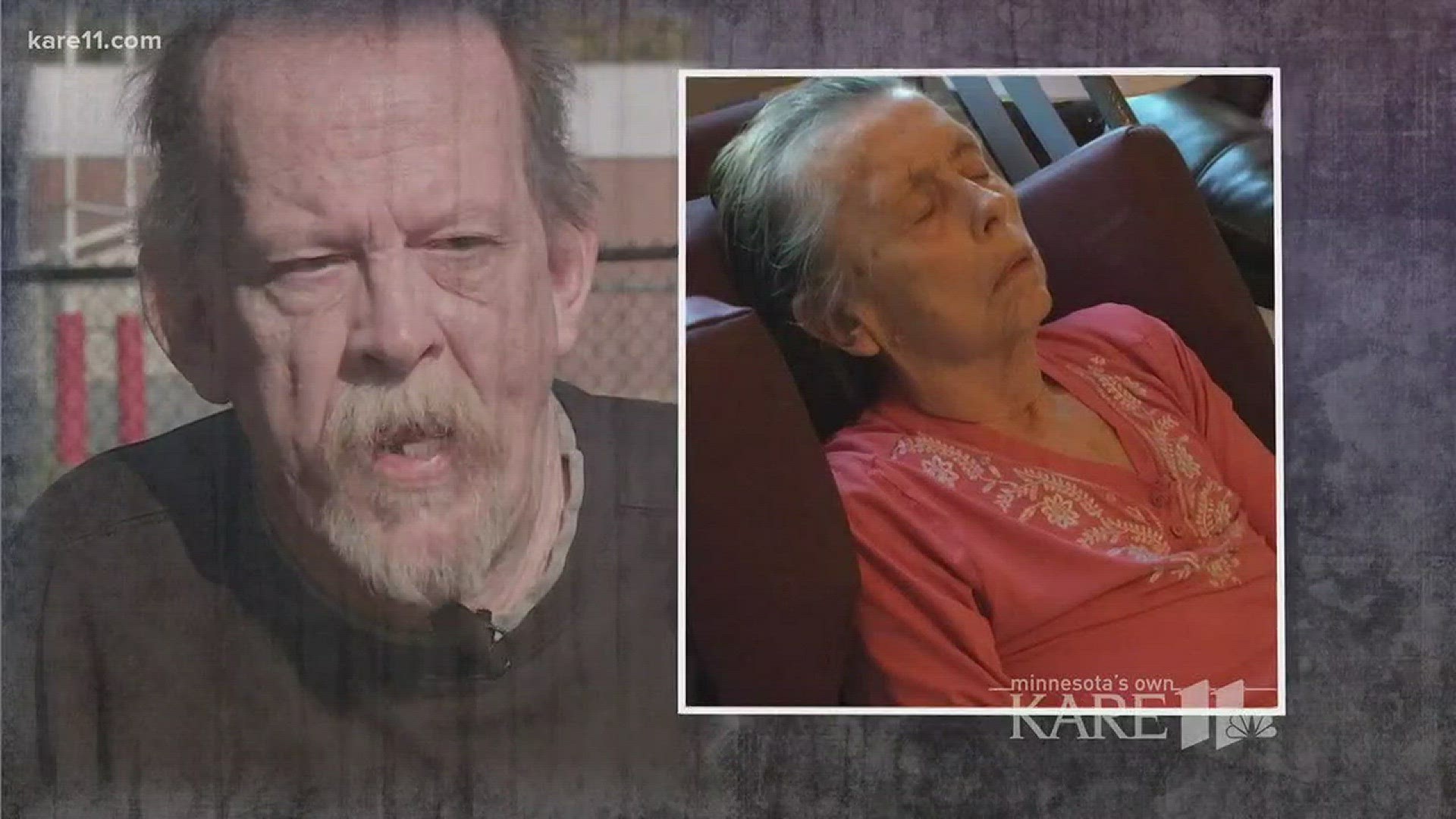

“She couldn’t cry out. She couldn’t push him off. She couldn’t tell anybody. She just had to lie there and take it,” said her son Bob Krause.

David DeLong was eventually criminally convicted of the assault.

But when state regulators investigated, they found Heritage House did nothing wrong, even though court records obtained by KARE 11 showed when another worker discovered DeLong in Krause’s room with his pants and underwear around his thighs, Heritage House waited more than an hour and a half to call police.

By the time officers arrived, someone at the facility had washed Jean Krause’s nightgown and mattress pad, destroying potential evidence.

“Until the people who are in charge are held accountable for this, nothing’s going to change,” Bob Krause said.

Bob says he wasn’t told about the attack until a prosecutor called him several months later. By then, Jean Krause had died.

“I’ve asked myself over and over again, why wouldn’t they say anything and the only thing I can come down to is, you know, fear of being exposed,” Bob said.

Why is that delay so significant? In part, because it may have shielded Heritage House from a lawsuit.

Unlike most states, in Minnesota the law says a civil suit dies with the victim.

So, when Jean Krause passed away, so did Bob’s chance to hold Heritage House accountable in court.

“It’s one of two states in America where if you run out the clock and that person dies for an unrelated reason, the lawsuit dies with the person,” said Mark Kosieradzki, an attorney who specializes in nursing home abuse and neglect cases.

Kosieradzki says many families believe the courthouse is the only place for justice. That’s because records show the Minnesota Department of Health investigates fewer than 1 in 10 maltreatment complaints. Fines for abuse and neglect top out at just $5,000 – even for a death.

At the legislature, there are new calls to change the law to let families of abuse victims sue even if they have died. Legal advocates say it would “equal the playing field” between families and the facilities they entrust to care for their elderly relatives.

Victims like Suzanne Edwards. Last year, KARE 11 reported how she was verbally abused and threatened by two aides as another secretly recorded on a cell phone.

On the videos, the aides can be heard taunting Suzanne for not wearing underwear, screaming at her and mocking her.

According to court records they “pulled out a lighter” and “put the flame near Suzanne’s face,” threatened her and flung her nightgown up, exposing her nude body. The two women were convicted criminally of abuse.

“I was terrified for my mother,” said Kent Edwards, Suzanne’s son.

But when state regulators came to investigate the complaint, they found that while the aides were at fault, the facility was not. Kent says he was angry the state didn’t find the facility at fault for what he sees as poor supervision and training.

“They don’t even get a slap on the wrist,” he said.

Kent wanted to file a civil suit and was working with an attorney when his mother passed away. “And with that the lawsuit passed,” he said. “The civil suit went away.”

Mary Cleary’s family faced a similar roadblock. She broke both of her femurs during a lift gone wrong at her nursing home.

In a haunting cell phone video, Mary is seen describing her pain. “They said oh you didn’t break any bones and I said I know I did. I could kind of hear them,” she said. “I was screaming and I couldn’t really help it.”

She would suffer for 19 hours in bed before being taken to the hospital.

“Neglect, definitely,” said her son Butch Cleary. Mary’s children wanted to file a lawsuit but she died just weeks later. Case closed.

“If you harm someone but that harm isn’t the cause of death, the lawsuit is over,” Kosieradzki explained.

The Insurance Federation of Minnesota opposes changing the law.

“These cases are always driven behind the scenes, by a lawyer who stands to make a lot of money,” said Mark Kulda, a spokesperson for the Insurance Federation.

Kulda insists lawsuits would only increase costs for everybody, not improve quality.

“Those higher insurance costs get paid, get passed along to consumers who have to pay more for the care,” Kulda said.

In the past, Insurance companies and groups representing care facilities have helped block changes in the law.

Senator Jim Abeler (R-Anoka), who sits on the Aging and Long Term Care Committee, says this year could be different.

“For the first time, the advocates and the families are at the table and they are being listened to,” Abeler said.

Bills to address the elder abuse crisis in Minnesota are slated to be filed in the legislative session that began this week.

It won’t change what Jean, Suzanne or Mary endured.

“The only one who paid for this is my mother,” Bob Krause said.

But their families hope the threat of a lawsuit protects someone else’s mom. Giving facilities the incentive not to run out the clock, but to clean up their act.

“What matters is when one of them goes to jail or when they end up having to pay to settle a lawsuit. Then they’ll listen,” said Krause.