KARE 11 Investigates: A mother's despair as she tries to get mental health care for her daughter

State failures to provide treatment for kids with mental illness and histories of violence have left them in jails, families desperate and community safety at risk.

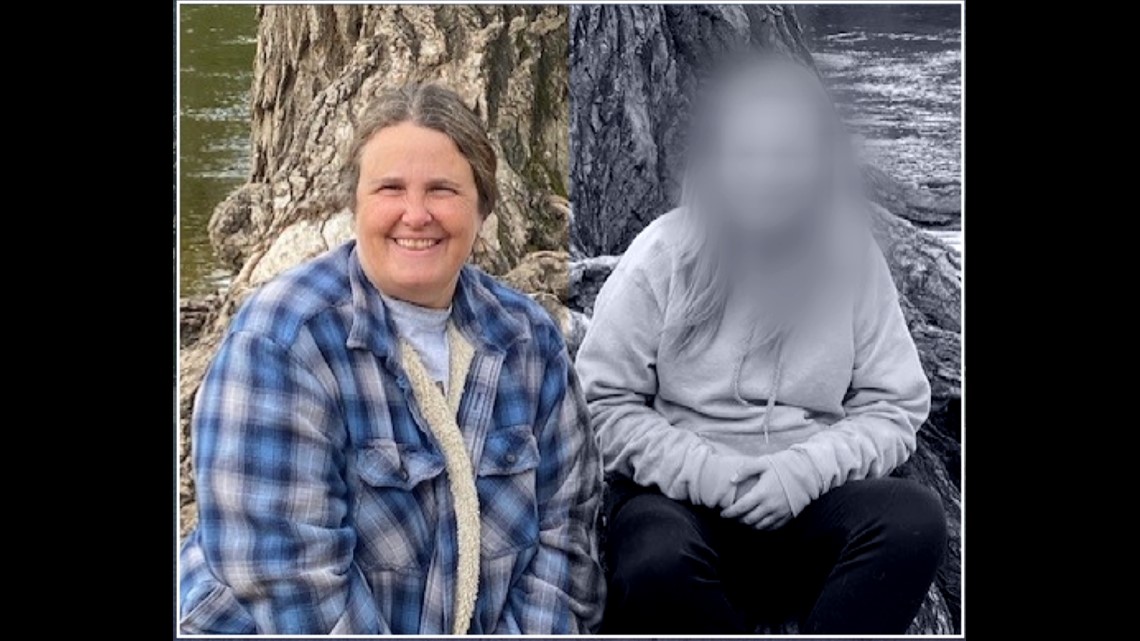

As Dawn looks through her daughter’s room, it’s a reminder that the girl has rarely slept here the last few years.

Instead, the 15-year-old girl’s life has been on a seemingly endless cycle for years, bouncing from juvenile detention to group homes to hospital emergency rooms for mental health crises.

In between, she’s run away more times than Dawn can count. She’s assaulted her parents numerous times, each one sending her to juvenile detention.

“It just goes around and around and around,” said Dawn. KARE 11 is not using her last name to protect her daughter’s identity.

Dawn doesn’t want her daughter in a juvenile jail, a facility never designed to provide the type of mental health treatment her daughter needs.

“That is not the place for her,” she said.

“But,” she adds, “there is no place for her.”

That’s the reality in Minnesota for kids like Dawn’s daughter, children who suffer with mental illness and have histories of aggression or violence.

Repeated failures

Too often, the state’s failure to provide adequate mental health treatment for those kids has left them sitting in detentions, their families pleading for help and putting communities’ safety at risk, a KARE 11 investigation has found.

In an earlier story, KARE 11 documented how a teenage boy with severe mental illness was held for months in juvenile detention – often in isolation, only able to talk to his mother through a 6-by-18-inch slot designed to pass food trays into his cell – because no treatment program in the state would take him.

Most private treatment centers won’t admit kids with histories of violence. For those that do, the children are put on months-long wait lists as the facilities struggle with funding their operations and finding qualified staff.

Others have closed due to a lack of funding, resulting in kids being sent out of state for treatment. State records show nearly 400 Minnesota children have been shipped out of state during the past four-and-a-half years.

Meanwhile, the state’s only secure mental health hospital for children is in Willmar, a two-hour drive from the metro area, and currently operates at just 25% capacity. Licensed for 16 kids, it’s only treating an average of three-to-four at a time.

“Right now we know that we need more beds,” said Nikki Farago, a deputy commissioner with the Department of Human Services. “We know that we need an increase in providers. We don’t have enough to serve the kids that need to enter this type of care.”

And Dawn worries for her own safety. Her daughter has stabbed her, threatened to poison her and set her on fire as she slept, Dawn said.

As she waits for her daughter to be released from juvenile detention, there will be only one place for her to go – home.

“I love her. I love her dearly.”

But, she says: “We keep our sharp knives locked up.”

Months of waiting

This is not the life Dawn imagined for her daughter when she adopted the girl when she was 8.

The girl grew up a victim of parents who were deemed “palpably unfit” to care for her, according to court records. She suffered from a traumatic brain injury, medical neglect, abuse, and maltreatment, according to medical records. She would be later diagnosed with personality disorder, PTSD, and reactive attachment disorder.

Dawn wanted to give her a new start, but around age 10 she said the damage done by the abuse had begun to show. Small resistances turned into screaming. She became aggressive.

At age 12 she was hospitalized several times for mental illness. She went to juvenile detention for the first time at age 13 for stabbing her mom.

What Dawn calls a “hopeless loop of chaos” started: After an arrest she would be released to a group home, or a hospital or a treatment center, only to go home and run away several times before she assaulted her parents again and was sent back to juvenile detention.

She has spent about nine months combined in detentions in the last two years.

In December, as the girl again sat in jail, a psychologist advised against sending her back to her parents, saying it would be unsafe for her and them.

Instead, the doctor recommended the girl be placed into a Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facility – or PRTF – which offers a high level of 24-hour care designed for kids like Dawn’s daughter.

The prospect of sending her daughter to a PRTF gave Dawn hope.

“If we can get her to the proper level of care, that she can be healed and come back to us, come back to our family and have the life that we imagine could be so great for her,” she said.

Unfortunately, there are only three licensed PRTF facilities in Minnesota, including one in Duluth, Northwood Children’s Services.

“That is the only one in the state that will accept her,” Dawn said.

The problem: Her daughter is on a 9-to-12-month waiting list to get in.

Lack of staffing

The state legislature authorized the use of PRTFs in 2017 specifically for kids struggling with mental illness who have a history of severe aggression, or who are a risk to themselves or others.

“Most of our kids are aggressive. That’s why they’re here,” said Northwood’s CEO Larry Pajari. “Unfortunately, (they have had) probably 8-10 failed placements before they’re here.”

Though DHS set a goal to have 300 beds by next year, there are currently only 46 staffed beds available, none of which are in the metro.

That’s created a terrible backlog.

“It can be over a couple hundred kids at a time,” said Pajari.

Farago of DHS blames staffing shortages for the lack of open PRTFs beds.

She said that’s also the reason the Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health Hospital in Willmar only treats three-to-four kids at a time.

“It comes back to workforce,” she said. “These are incredibly high-need, acute cases. And that means that we need highly skilled, highly specialized staff that also care about kids.”

Another problem, said Pajari, is that for years it seemed Minnesota didn’t want residential treatment programs like his.

“Twenty-four-hour cares were seen as an institution and had a bad label so to speak,” he said.

Facilities specifically targeted for kids at risk of committing crimes closed, such as the Hennepin Home School and Ramsey County’s Boys Totem Town, without any alternatives in place.

But in the past few months, Pajari said he’s seen a significant change, including the state increasing the reimbursement rates for treatment centers.

“I think we’re heading in the right direction,” he said. “The state really needs to find ways to fund (PRTFs). Kids deserve a chance.”

Sent back home

After Dawn’s daughter came home from juvenile detention in late September, the predictable happened. She ran away numerous times. Typically, Dawn calls the police, who take her daughter to a hospital, where she’s discharged and sent right back home.

Dawn said her daughter has become suicidal. Lately she said she’s run away to steal razors and harm herself.

“My heart breaks for her,” she said.

If her daughter is not able to get into Northwood in Duluth soon, Dawn said “our fear is that between now and then, something devastating is going to happen.”

Watch more KARE 11 Investigates:

Watch all of the latest stories from our award-winning investigative team in our special YouTube playlist: