KARE 11 Investigates: An accused sexual predator, a decade of safety net failures

Part 5 – “The Gap: Failure to Treat, Failure to Protect” – Too mentally ill to be tried for rape, DHS and the courts said he’s safe to live on the streets.

At 18-years-old, Omar Isse was already so mentally ill and likely to cause harm that a Hennepin County judge ordered him committed to the Department of Human Services for treatment in 2009.

It didn’t work.

Over the next 11 years, Isse cycled from the streets to a seemingly endless array of commitments, hospitals, group homes, jails, and back to the streets, as his potential to cause harm was sadly realized.

He faced an assault charge in 2013 for stabbing a man with a box cutter; an aggravated robbery charge in 2017 where the victim says Isse tried to kidnap her. He was charged in 2020 for allegedly raping a woman in public, then in September charged with attempting to rape a staff member at a group home.

A judge released him again, and he went missing, only to be found after KARE 11 reported on his whereabouts.

His story may not end there.

Though Isse is back in jail, if his decade-long pattern continues, the courts and DHS will release him, where he’ll go through the same cycle of group homes, arrests and jail, and still fail to get the help he needs.

“It’s like a ticking time bomb,” said his longtime attorney, Mark Gray. “We’re just kind of waiting to see what happens.”

A closer look at Isse’s case history reveals systemic flaws, loopholes and outright failures in the state’s criminal justice and mental health safety nets to adequately treat his mental illness and protect the public, a KARE 11 investigation has found.

Isse is among thousands of other criminal suspects known in Minnesota as gap cases, mentally ill and found incompetent to stand trial, but then released back into the community without appropriate supervision or treatment.

KARE 11 has already exposed gap cases where mentally ill and incompetent suspects have gone on to commit brutal assaults, rapes and murders.

Some state legislators have pledged reform, but cases like Isse’s make clear that change is urgent, said Rep. Tony Albright. “There are going to continue to be tragic events,” he said.

As the Republican lead of the House Human Services Finance and Policy committee, Albright has reviewed Isse’s case and others. “Families will be devastated and lives ruined,” he said.

Chapter 1 'Just the beginning'

If anyone would know Isse best, it may be Gray, who was appointed to represent him during his client’s first commitment in 2009.

Isse came to the United States sometime when he was 10- to 12-years-old, Gray said, though he isn’t sure how. Gray said Isse has no family that he’s aware of.

In years of court hearings, Isse’s immigration status has never been questioned, Gray said.

At 18, Isse was hospitalized and told his care providers he was homeless and stayed in whatever building he could find, records show. A doctor tried to evaluate him, but found Isse so uncooperative and agitated, he was “basically uninterviewable.”

Isse’s evaluator told the judge, “this was just the beginning of a major mental illness for him.”

A judge committed him for mental health treatment that year, and then again in 2011 and 2012. But he was repeatedly released and sent to group homes and halfway houses.

Along the way, he would be charged with numerous minor crimes, such as trespassing and theft, all dismissed due to his mental illness – making him a “gap case.”

In October 2013 Isse was at a south Minneapolis mall when he stole a man’s phone and sliced his stomach and leg with a box cutter, court records show.

A judge ordered a psychologist to evaluate Isse’s ability to stand trial.

Isse told the doctor he heard voices. “They always tell me to kill myself and to kill others,” according to court records.

A judge committed Isse to DHS a fourth time after he was again found incompetent to stand trial.

But for the first and only time in his life, Isse would be restored to competency and in 2015 plead guilty to a gross misdemeanor assault in the box cutter case.

Today, despite nearly two dozen charges in the last ten years, that is the only conviction Isse has on his criminal record. The rest have either been dismissed or put on hold due to his mental illness.

That includes a case from July 2017, when Amina Botan feared Omar Isse was trying to kidnap her.

Chapter 2 'Please help me'

Botan was at a south Minneapolis Somali mall when she said Isse walked up to her on the street, saying he was sick and needed a ride home.

“He said, ‘Please help me,’” she told KARE 11.

She let him in her car, but soon she said he started touching her.

She said she stopped the car and told him to get out; he refused and told her to keep driving because he had a gun.

She screamed for help as she jumped out of her car. Isse followed her, she said, grabbed her by the arm and tried to pull her back into the vehicle while shouting to witnesses that she was his wife.

“And I say, ‘No. I’m not his wife. Help!’” Amina said.

Isse fled, stealing the woman’s phone and car, according to the criminal charge.

After being arrested and taken to jail several days later, Isse was so distraught that he spread feces in his cell, according to court records. He broke a food tray and held a plastic shard to his neck. When he went to a court hearing, guards needed to put a spit mask on him.

Isse was again found incompetent and for the fifth time committed to DHS, which sent him to the Anoka Metro Regional Treatment Center, a 110-bed hospital on a secure campus.

DHS released him on what’s called a “provisional discharge.” But he would spend the next two years cycling between six group homes, each of which evicted him, court records show.

A judge committed him to DHS for a sixth time.

While on provisional discharge he continued to rack up more criminal charges — trespass, disorderly conduct, damage to property and assault. In the latter case, Isse allegedly punched an HCMC security guard in the face after refusing to leave the hospital.

Isse would be taken back to jail but was still incompetent to stand trial in any of his pending charges. A judge committed Isse to DHS for a seventh time in 2020, and he was sent back to the secure Anoka treatment center.

But within months the agency would again release him, even as his violence escalated.

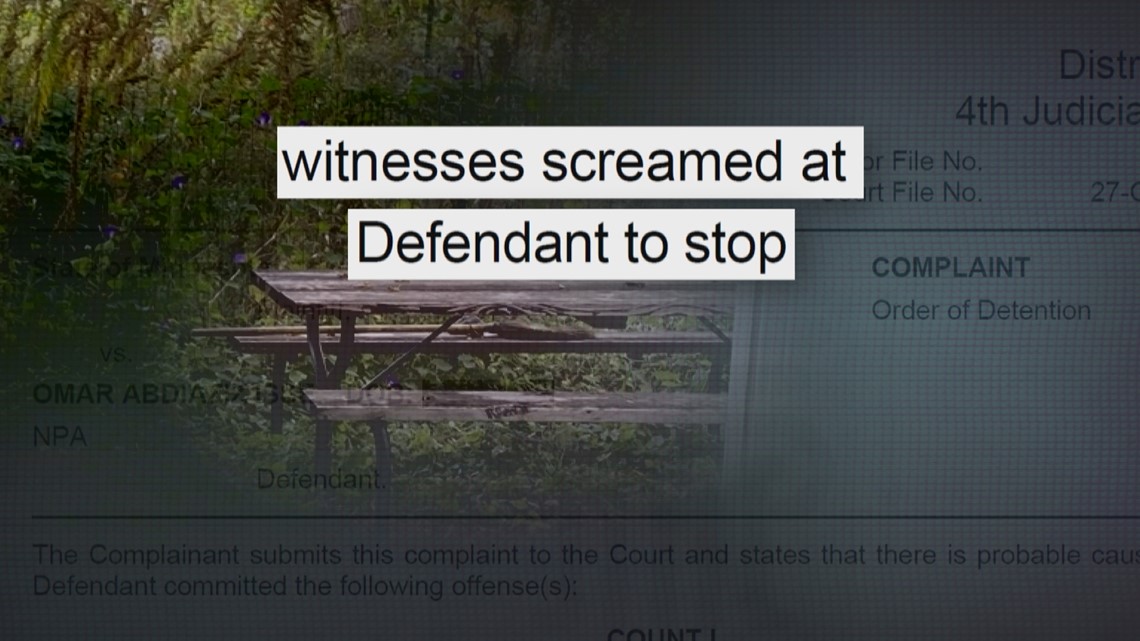

Chapter 3 Witnesses screamed at him to stop

Two years earlier, in 2018, citing a lack of hospital beds, DHS began releasing mentally ill suspects like Isse back to the community even if they were still incompetent to stand trial.

Since that time, DHS said at least 665 patients with pending criminal charges have been provisionally discharged.

Dr. KyleeAnn Stevens, DHS’ chief medical officer, defended the practice in an interview with KARE 11. “If we feel there is not a provisional discharge plan that is safe for the individual or for the community, we’re not going to pursue that plan.”

But as KARE 11 reported, numerous cases of beatings, sexual assaults and even murders show those releases often are not safe.

That includes Isse. Less than two months after the agency provisionally discharged him in June 2020, Isse stood with his pants down at a south Minneapolis picnic table as witnesses screamed at him to stop raping an unconscious woman, according to the criminal charge.

Isse ran by the time police arrived, but they were quickly able to find and arrest him.

Like so many times before, he was found incompetent in that case and sent back to the state’s secure campus in Anoka in October 2020.

Chapter 4 A revolving door

His status was reviewed in 2021 and he was recommitted to DHS in February — for the eighth time.

Then in May, the agency sent a notice to Hennepin County Court that Isse would again be provisionally discharged back to the community.

That presented a dilemma to a judge overseeing his case, Lisa Janzen. Deny the release, and Isse would go back to jail even though he still was still unfit to stand trial.

But if Isse went there, Janzen wrote, “the court would have to make the impossible decision as to whether to keep the incompetent defendant in the jail not receiving treatment with a suspended criminal case, or, to release the defendant to the street.”

Citing earlier court rulings questioning the constitutionality of holding mentally ill patients in jail indefinitely, Janzen chose the street and authorized his release.

It would be up to DHS and Minnesota’s mental health system to supervise him.

Isse again went to a group home, but only three weeks later, his provisional discharge was revoked after he repeatedly walked away from the home, used drugs, and refused to take his medications, according to court records.

A judge ordered that Isse be immediately sent back to Anoka, but it’s unclear if he ever went there. Instead, court records show he was at the Hennepin County Medical Center, which provisionally discharged him in late August.

While declining to talk about Isse’s case, a DHS spokesperson said state law allows hospitals to release civilly committed suspects who are waiting to be admitted to a DHS-operated facility.

“In these cases, DHS does not have any input into the community hospital’s decision to provisionally discharge,” the spokesperson said.

An HCMC spokesperson referred to the same state law when asked about Isse’s case.

Isse would end up in yet another group home — this one in Fridley.

Chapter 5 Released again, another attack

Two weeks after his release from HCMC, a terrified woman ran to Laura Carlson’s door.

“She was crying and screaming.” Carlson said. The woman was fleeing from a violent sexual attack.

According to the criminal charge, Isse suddenly attacked a staff worker at his new group home, grabbed her neck and forced her to the ground, where he humped her as he tried to take off her clothes. He punched her in the face and chest as she cried out for her sister, who was also working in the home.

Carlson said she had no idea who was living next door. “I mean, geez, that dude was like a sexual predator,” she said.

Fridley police said they had no idea Isse was there, either.

Because he’s been found mentally incompetent and has never been convicted of a sexual assault, Isse does not appear on any sex offender registry.

And while suspects charged in Hennepin County with sex assault and other crimes are at least monitored by probation when they’re released from jail awaiting trial, that’s not the case for mentally incompetent defendants like Isse.

“Clients who are civilly committed are not under criminal court jurisdiction during that commitment,” a county spokesperson said.

Despite a severe mental illness, an aggravated robbery charge, two sexual assault charges, eight commitments to DHS, numerous failed group home placements, Isse would again go free — and unwatched.

The day after his arrest in the Fridley group home assault, Isse stood in front of Anoka County Judge James Cunningham, who grew impatient with him.

“I need you to listen. Right now, I need you to listen,” Cunningham ordered him.

“What do you mean?” Isse replied. “I’m listening, man.”

Isse rambled about the home. “In the basement, they were having a lot of sex,” he said.

“We’re done here,” Cunningham said.

The judge ordered his release — without requiring bail — and issued a no contact order prohibiting Isse from going to the group home where in theory he was still civilly committed.

In effect, Judge Cunningham’s order sent Isse back to the streets.

“That’s not good for him it’s not good for society,” said Gray, the attorney who has handled his civil commitment cases for more than a decade.

Chapter 6 Missing, until KARE 11 found him

The next week, Isse failed to show at a Hennepin County court hearing to determine if he was competent to stand trial in connection with the 2020 picnic table rape.

Judge Janzen, who authorized Isse’s release after he was charged with that assault, said during the hearing that DHS should know where Isse was and set another hearing for a month later.

But DHS told the court that Isse’s whereabouts were unknown, records show.

In the weeks that followed Isse missed his next court hearings on sexual assault charges in both Anoka and Hennepin counties.

On Oct. 19, at the same time the Hennepin court hearing was taking place, KARE 11 found him living in a south Minneapolis homeless shelter and walking through the same Somali mall, where four years ago, he approached Amina Botan before allegedly attacking her.

He had been missing for more than a month.

Two hours after KARE 11 aired a story revealing how the courts and mental health officials had lost track of an accused rapist, records show Minneapolis police arrested Isse at the same homeless shelter.

He’s back in jail again and held on $50,000 bail.

But keeping him there will only make his mental illness worse with little hope that he’d be restored to competency to face charges in the picnic table assault, his criminal attorney argued at a hearing last week.

For now, Judge Janzen ordered him held in jail so he can be re-evaluated to determine if he is competent to face his criminal charges.

Left unsaid: If he’s again found incompetent and sent back another time to DHS for treatment, he could be provisionally discharged yet again, sending Isse back into the same cycle he’s been in for years.

The first woman he’s charged with attacking wants to know: How many victims will it take before Minnesota gives Isse the level of care and oversight he needs?

“He scares me, really scares me,” Amina said.