MINNEAPOLIS — Four years before George Floyd, another man said he was beaten by a Minneapolis police officer who kneeled on his neck.

“I thought I was gonna die,” Idrissen Brown recalled.

But records show Brown’s complaint about police misconduct was never investigated. What’s more, it was not even counted in the city’s official list of police complaints.

He is not alone.

Hundreds of people who started the complaint process since 2016 have had their information classified as a so-called “inquiry” – not a formal complaint – a joint KARE 11 and NBC News investigation found.

When a complaint is classified as an “inquiry” it is not investigated and never listed in a police officer’s complaint file.

City records show there have been more than 100 cases classified as “inquiries” each year since 2016 – a total of 791 through early June 2020. More than 230 of them came in the month after George Floyd was killed as people who watched the viral video called to complain and protests erupted.

Even if you exclude that sudden flood of complaints, it means roughly one out of five people who tried to complain haven’t been counted in the official complaint statistics.

In June, a KARE 11 investigation revealed that only about two percent of official complaints have resulted in disciplinary action.

If the “inquiries” were included in the totals, the discipline rate would be even lower.

“Scariest moment of my life”

Idrissen Brown says he and his girlfriend were watching a movie well after midnight on March 13, 2016 when they heard knocking on their South Minneapolis apartment door.

“As soon as I opened the door, the officer grabbed me by the collar and snatched me out into the hallway,” he said.

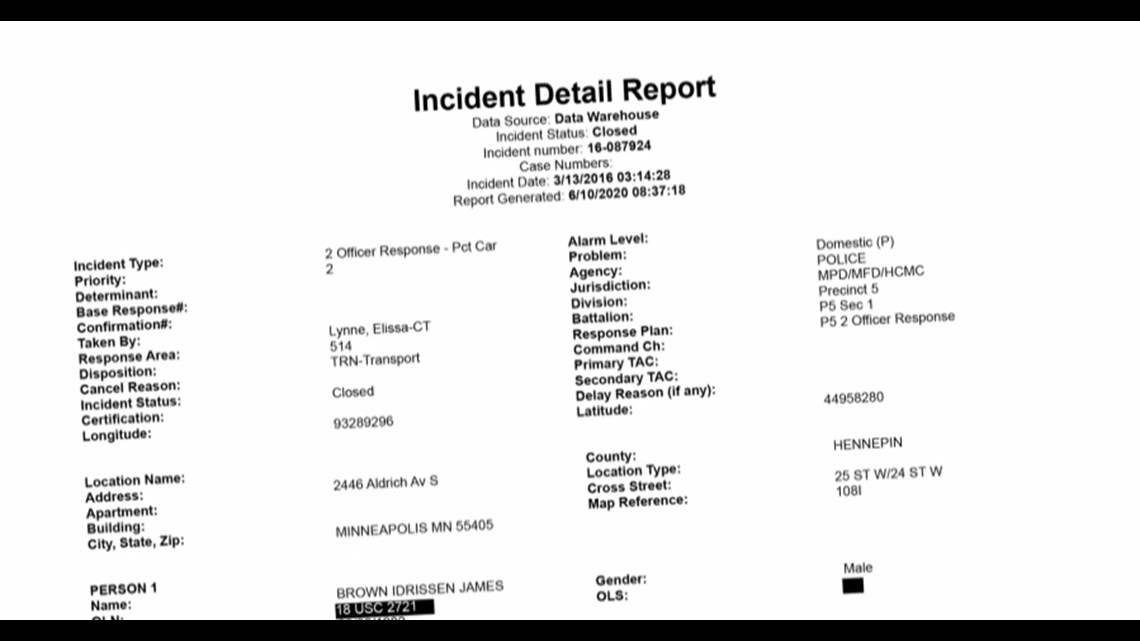

A Minneapolis police incident report confirms that police were sent to their apartment building on Aldrich Avenue South after a 911 caller reported hearing a man and woman “screaming at each other” that night.

But the report doesn’t describe what Brown says happened next.

“He threw me down a flight of steps, and then he jumped off from the top of the steps, kneed me in the back of my-- of my neck, and then he started punching me in the back of my head,” Brown told NBC Correspondent Gabe Gutierrez. “And then he placed cuffs on me.”

The officers put him in a squad car. But instead of taking him to jail they drove to another location, where Brown says the beating continued.

“He opened up the back seat and started to beat me some more,” Brown recalled.

“I thought it was over. I thought I was never gonna see my wife again,” he said. “It was the scariest moment of my life.”

Released with no charges

Records show Brown was released that night without being charged with a crime.

Although there was no arrest, the police incident report confirms part of Brown’s story. It says officers did transport him in a squad car and “dropped [him] off at moms house for the night.” Brown says officers dropped him off on the side of the road and he had to walk home.

The next morning, Brown says he tried to file a complaint about alleged abuse by police. He says he contacted the Fifth Precinct and spoke to a sergeant. “She said that she would take my complaint, and she gave me the number to Internal Affairs,” he said.

Brown says he followed up. “I contacted Internal Affairs, like, three, four times, for almost a month, straight. I didn't get any word back.”

Eventually, he gave up.

“I felt like nobody cared,” he said. “I felt like, they get away with it so much, that, ‘Hey, I was just lucky to not die.’"

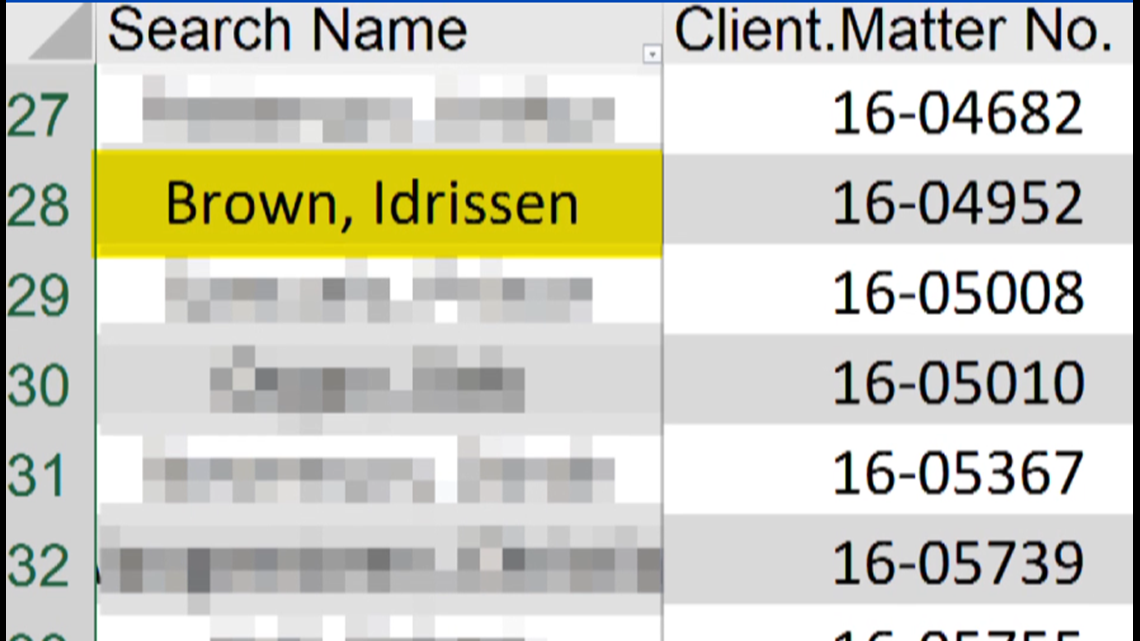

Case number: 16-04952.

The city’s own records confirm that Brown started the complaint process.

The Minneapolis Office of Police Conduct Review entered his name in a computer database, records show.

He was even assigned a case number: 16-04952.

Instead of including Brown’s case on the official list of police complaints, however, it remained on a separate list. They’re called “inquiries.”

Until NBC News and KARE 11 began asking questions – and filed formal requests under the state’s records law – the inquiry list containing hundreds of entries had not been made public.

Why are complaints like Brown’s not counted as official complaints?

Minneapolis officials cite a Minnesota state law that says complaints must be “signed” before they are considered official.

The law reads: “An officer's formal statement may not be taken unless there is filed with the employing or investigating agency a written complaint signed by the complainant stating the complainant's knowledge, and the officer has been given a summary of the allegations.”

Minneapolis interprets that to mean a phone call – or even a series of them – isn’t enough to launch an investigation.

In an email, Andrew Hawkins, the Chief of Staff for the city’s Office of Police Conduct Review, said, “OPCR cannot legally conduct an investigation and officer interviews until that standard has been met.”

Despite his repeated phone calls, Brown says no one told him about the signature requirement.

A pattern of misinformation

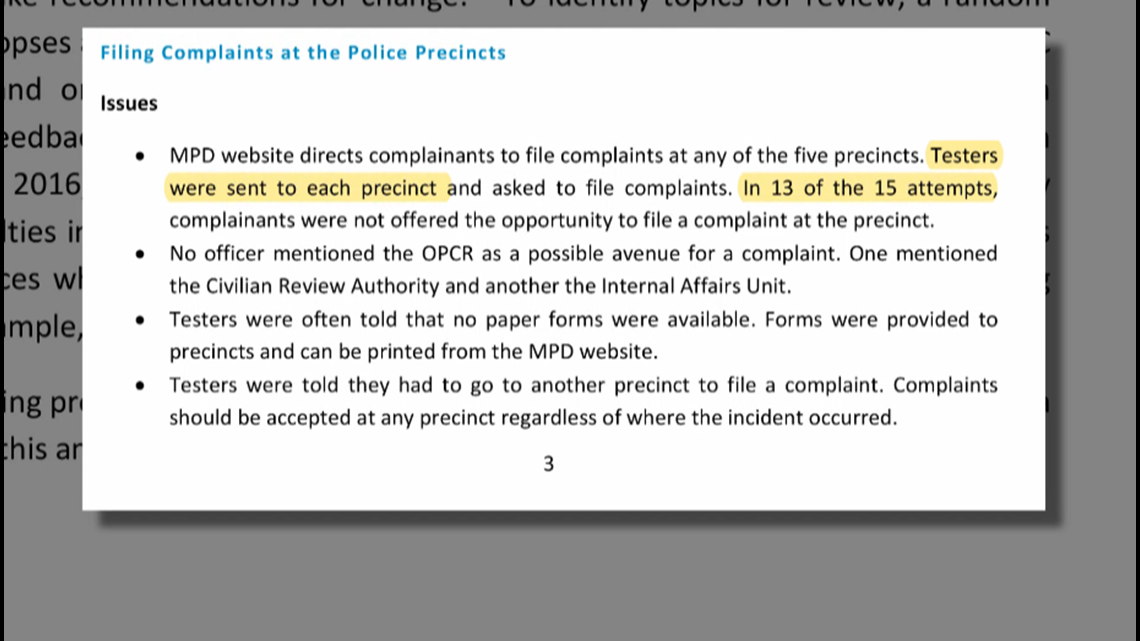

A city report documented widespread problems in the complaint process around the same time Brown tried to file his complaint.

The findings were detailed in an August 2016 report, just five months after Brown’s encounter with police.

After hearing public complaints about “roadblocks” in the complaint process, the Minneapolis Police Conduct Oversight Commission sent undercover testers to police precincts to try to file complaints.

In the overwhelming majority of cases – 13 out of 15 – the testers were not given correct information, according to the report.

In the wake of that investigation, the city promised reforms.

Continuing problems?

Since that report, though, other people who tried to complain about police misconduct tell KARE 11 they still were not told about the signature requirement.

Courtland Pickens says he tried to complain in person at a police precinct last year after he says young women in his church choir were pulled over and held at gunpoint.

The city’s inquiry records show Pickens began the complaint process last October – assigned case number 19-14939 – but his case was never classified as an official complaint.

“Did anyone ever tell you: You had to sign the complaint?” asked KARE 11’s Lauren Leamanczyk.

“No,” Pickens replied. He’s upset his complaint was never investigated.

“It’s heartbreaking to me, honestly, because the youth that I work with were so distraught,” he said.

Pickens was one of the people listed in city records as filing inquiries over the past two years – between 2018 and May 2020 – KARE 11 and NBC News was able to interview.

Of the 19 people we contacted, 13 said they did not know they needed to sign something before their complaint would be considered.

Minneapolis responds

KARE 11 requested an interview with Imani Jaafar, Director the Minneapolis Office of Police Conduct Review (OPCR) for an interview. She did not respond.

In an email, a city spokesperson said, “Typically, inquiries are followed up with two phone calls and a letter or email. If we don't receive a response, we cannot proceed.” Each person is supposed to be told about the signature requirement – and the city allows them to do that online.

City officials declined to comment on specific cases, citing Minnesota’s Data Practices law.

Minneapolis officials say their hands are tied by state laws about what can be classified an official complaint – and how much information about them can be released to the public.

In addition to the signature issue, the city says some cases remain classified as inquiries because the complaint involves an officer from a different police agency. Minneapolis only investigates complaints about its own officers.

Staffing is also an issue. Over the past two years Minneapolis has averaged 600 police complaints per year – not counting the additional inquiries.

But OPRC says it currently has just one intake investigator to handle those complaints. A second investigator position has not been filled because of a hiring freeze imposed due to COVID-19.

City officials also say less serious complaints result in “coaching” of the officers involved. However, coaching is not considered formal discipline and, therefore, is not included in the statistics.

If coaching was included, the city says 18.5% percent of the formal complaints received from 2018 through 2019 resulted in some form of corrective action.

“Don’t be silent”

Idrissen Brown says he still feels the effects of his encounter with police – especially after watching the video of George Floyd’s death.

“I'm in therapy, dealing with P.T.S.D,” he explained. “I immediately told my wife, like, ‘Look at these cops. It's the same thing they did to me.’”

He’s moved away from Minneapolis but says he can’t forget what happened. “I'm trying to put everything behind me, but it's hard.”

Now he wonders how many other complaints like his have slipped through the cracks.

“How does a case like mine get buried or lost?” he asked.

Despite his own experience with the complaint process, Brown says he thinks it’s important that people continue to report police misconduct.

“I would say, ‘Come forward. Don't be silent,’” he said. “Silence is a killer and it'll continue to happen unless you use your voice to speak up.”

The NBC News Investigative Unit contributed to this report.

This story began with a tip. If you have something you’d like us to investigate, send us an email at: investigations@kare11.com