MINNEAPOLIS — A local judge has sharply criticized Hennepin County officials for holding a sixth-grade boy in juvenile jail — illegally — for weeks.

The case highlights a longstanding problem — too few treatment options for kids with mental health conditions accused of violent crimes. By law, if they are found incompetent to stand trial, they are supposed to be released.

Rather than release the boy and return him to his mother, county child protection officials petitioned the court to keep him in a secure mental health treatment facility. But, so far, the county hasn’t been able to find a facility in Minnesota able to accept him.

That has left the young boy languishing in jail — without treatment or even the ability to go outside — for nearly a month.

Ongoing court battle

At a recent hearing, the 12-year-old boy walked into court, barely as tall as the deputy’s chin, and took his seat as adults argued about whether and when he could leave the juvenile detention center.

Accused of multiple car thefts since the age of 11, he has been found incompetent to stand trial due to mental health issues, his IQ and his young age.

Under Minnesota law, he must be released. Instead, he’s been held in custody at the Juvenile Detention Center because Hennepin County can’t find a mental health facility in the entire state that will accept him. And his mother, Kendra, tells the court without intensive treatment she cannot keep him safe at home.

KARE 11 is not using the mother’s last name to help protect the boy’s identity.

Kendra shared her frustration with KARE 11.

She says her son has been brought to the Juvenile Detention Center (JDC) and released time and again without the needed mental health resources.

“The kids, they sit and get all these cases, and they keep letting them go,” Kendra explained. “That’s not helping solve the problem.”

What her son needs, she says, is help with his mental health and trauma.

“These kids need help. Not just my child. all these kids need help,” she said.

Judge puts Hennepin County on notice

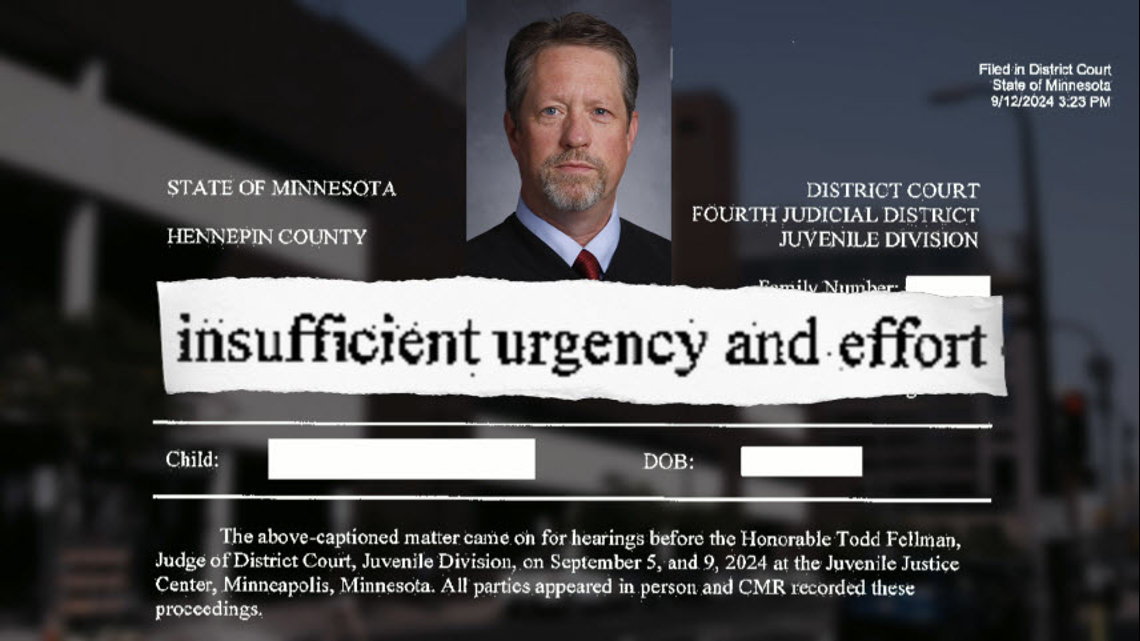

Judge Todd Fellman had ordered Hennepin County — who has legal custody of the boy through the child protection case — to pick the 12-year-old boy up from the JDC on Aug. 26 but the county refused.

The boy’s attorney Tracy Reid argued that puts them in contempt of the court’s order. Testimony in court showed conditions at the JDC are not appropriate for such a young child who has threatened suicide.

“It is bad faith to leave a child in an incredibly dangerous situation where he is in isolation and he is afraid,” she told the judge.

Hennepin County Program Manager Mandee Kleckner argued it’s the safest place for the youth right now.

“We’re just concerned. We don’t want him to get hurt or hurt someone else,” she testified.

Ultimately, Judge Fellman declined to hold Hennepin County in contempt – but warned the county that determination may not last forever.

In his order, he called out the county for “insufficient urgency and effort” to solve a problem they have known about for years.

Fellman urged Hennepin County to “seriously contemplate creating its own facility for children with complex needs,” given the fact that secure treatment centers around the state have routinely rejected Hennepin kids.

He noted the 12-year-old boy isn’t the only child facing the same dilemma.

Failure to provide treatment options

Since 2022, KARE 11 Investigates has been covering the gaps in the juvenile justice system because Minnesota lacks enough mental health placement options for youth who’ve been found incompetent to face criminal charges.

“They’ve been on notice for a very long time and we’re at the point where inaction is a form of action to not fix this problem,” said public defender Laura Baldwin who also represents a child stuck in the JDC.

Treatment providers in Minnesota are allowed to decline patients. Most will not accept children with a history of aggression or low IQ scores — leaving many kids who’ve cycled through the justice system and the courts without options.

When Hennepin County closed the Hennepin Home School — its secure treatment facility — in 2021, they failed to open a new place to take the kids, many of whom have not been successful with in-home therapy options and run from less secure facilities.

“When the home school ended, we lost the place of last resort,” Reid said. “They didn’t create a new one. And they haven’t contracted with enough providers that they have a new place to put them.”

The county relies on a network of group homes that have the ability to decline youth with needs too complex or a history too violent. Psychiatric residential treatment facilities provide a higher level of care in a locked setting, but Minnesota has only four of them — and the wait lists can be months or even years long. Court testimony showed they rarely accept kids from Hennepin County.

In the case of Kendra’s son, the only placement Hennepin County officials can find is out-of-state, a thousand miles away from his family in Virginia. And it’s not even available until late September.

“None of the kids in Minnesota is getting help. They’re trying to send the kids far off to where us parents can only see our kids once a month,” said Kendra who opposes the placement.

No plans to build a treatment center

KARE 11 brought the concerns to Hennepin County Commissioner Jeff Lunde who has served on a state working group to address the issue.

He said any solution needs to be on a state level — not just Hennepin County. The report found massive roadblocks with licensing for treatment centers with varying levels of security, low reimbursement rates which make it hard for providers to afford to take more challenging kids, and a statewide shortage of qualified staff.

One-third of the beds in the state are currently empty because of lack of staffing, he said.

Because of those challenges, Lunde says Hennepin County has no plans to open its own treatment facility for these high-need kids.

“The question is: Will there be something there when we get to the point where we have a nice new building? Will it be staffed, licensed, accredited? Will we get reimbursements? As of right now, the way the system is working it won’t be,” Lunde said.

He says the task force has recommendations for state leaders and the county is working on the problem.

“This is one of our top priorities for public safety,” Lunde said.

But some families say they cannot wait for long-term fixes. They need help now.

“He’s not getting help”

Before the 12-year-old’s hearing, another family faced the same judge with the same predicament.

Latoya’s son, 16, has been held for months at JDC because the county can’t find a facility that can meet his needs.

He has a cognitive disability, depression and anxiety. He has been hospitalized for his mental health multiple times this year.

His mother Latoya says she’s been trying to get him help since he was a little boy.

Latoya, who works in health care, says she’s taken her son to therapy, psychiatry services and a mentorship program, and all have been unsuccessful. Now at the JDC, she says, “It’s a revolving door because no treatment is being done.”

The county says despite a nationwide search, they cannot find a facility that will accept the boy given his high level of need and intellectual disability.

“I want my son home, but I want him home safely,” Latoya told KARE11.

She fears without mental health treatment, he will continue to cycle through the system.

“They’re going to lock him up because they’re going to see violent behaviors. When really, they could have taken care of the violent behaviors if they would’ve just taken care of his mental health.”