FARMINGTON, Minnesota — Kathy worked the phones from her Farmington home, desperately trying to find a safe place for her 15-year-old son.

Preston has an intellectual disability, and had become increasingly volatile and physically violent. He was stuck at the hospital emergency room, not because he was physically ill, but because he’d been kicked out of his group home.

The hospital, M Health Fairview West Bank, said they could not treat Preston’s chronic condition. Kathy wouldn’t pick him up, because her county case manager said it wasn’t safe.

And so, Preston became one of a growing number of kids in Minnesota stuck in emergency departments because no one else will take them, something hospitals call “boarding”. The numbers have been increasing dramatically during the pandemic, even as hospital beds filled with COVID patients.

“I don’t want him there anymore than they do. I mean, it’s heartbreaking,” Kathy said. And while she missed her son, she didn’t see another option. “It’s a horrible situation. But I said he’s not safe to come home. I can’t have him come home.”

“I can’t keep him safe”

Preston has been diagnosed with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), a rare genetic disorder characterized by always feeling hungry and an inability to control food intake. It’s often accompanied by severe mood disorder and according to the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research, people with PWS are at a heightened risk of depression, bipolar disorder and psychotic symptoms.

In Preston’s case, physical outbursts increased as he entered his teen years.

“He’s the sweetest boy when he’s not angry,” said Kathy, who also has other children. She shared videos of Preston playing with his brother and sister, reaching over to give hugs.

But when Preston has outbursts, she said it’s scary to watch.

“He has hit and kicked me. He has hit my daughter. He ended up stabbing our dog one day. The dog that he absolutely adores,” Kathy said.

Just as concerning, Preston often tries to hurt himself.

“I can’t keep him safe,” she said.

Kathy thought she’d found a solution this past summer when Preston entered a crisis group home for children with intellectual disabilities. But right around Thanksgiving, that state licensed facility kicked Preston out, sending him by ambulance to M Health Fairview’s emergency department.

“I never had imagined that a crisis stabilization site would terminate services because they couldn’t handle the child,” Kathy said.

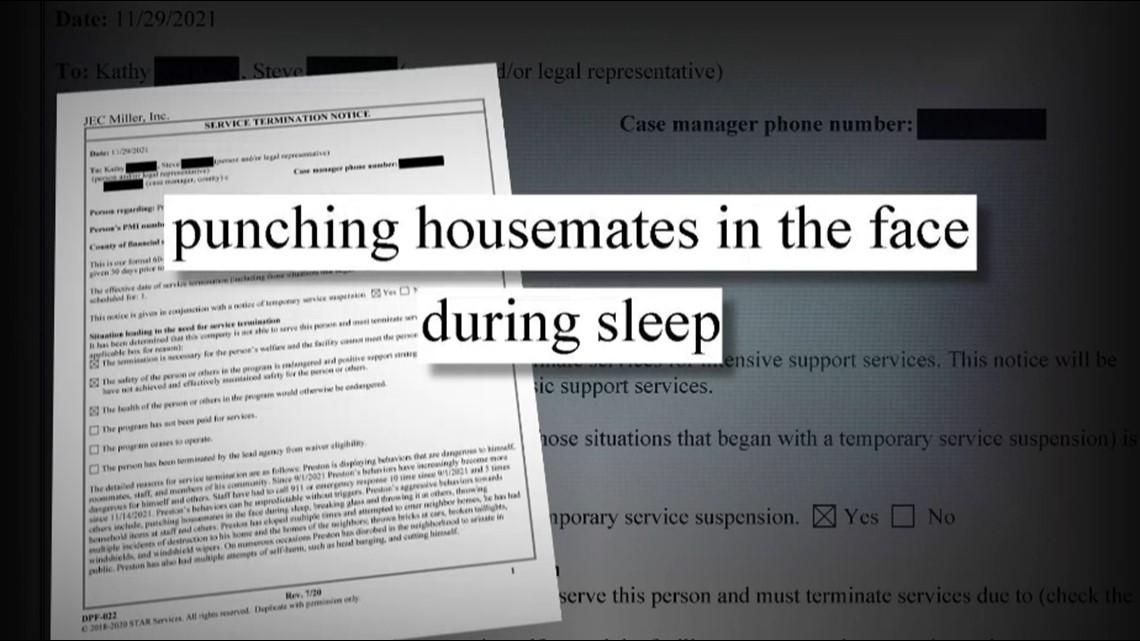

In the termination paperwork, the group home called Preston’s behavior “dangerous.” Officials said they had called 911 10 times, that he’d “punched housemates in the face” while they slept, eloped from the facility and thrown bricks at cars. They also said Preston “had multiple attempts at self-harm.”

Stuck in the Emergency Department

When Preston arrived at M Health Fairview, hospital staff assessed and stabilized him, but determined they couldn’t admit him. Facing a rush of COVID patients, hospital officials said they didn’t have room to keep him until Kathy found a permanent placement.

Dr. Allison Holt says it’s a decision the hospital often reaches when patients have chronic mental health or behavioral problems that require long-term care.

“If someone has chronic aggression or chronic behavioral outburst, that’s not something that can be treated in the hospital,” she explained.

M Health Fairview reports staggering increases in dumping youth “boarders” at the hospital.

System-wide, M Health Fairview says it has experienced a 140 percent increase over pre-COVID levels. What’s more, the average stay has skyrocketed from just two or three days up to 16.5 days at the hospital.

Most of the minors - more than two-thirds of them - are under the care of the counties or a group home. Hospitals contend even professionals are using the emergency department as a place to dump children in crisis.

“We have boarders that don’t need to be at the hospital, but have nowhere to go. They are dropped off at the emergency department. Their parents or their county protection workers won’t come and pick them up,” Holt said.

And while some may argue the hospital is the safest place, Holt believes it is not the best place for children.

“Going into a hospital is not benign. It’s traumatic,” Holt said, describing how the kids sit alone in empty hospital rooms.

Asked, “what’s the answer for these families?” she replied, “I think that’s the biggest question.”

The system: “Not in good shape.”

It is a question no one seems to be able to answer for Kathy or Preston. In the second week of their standoff, M Health Fairview insisted Preston needed to go home. Kathy still didn’t think she could keep him safe.

“I feel like he’s sitting there. Have I abandoned him?” she asked herself. “I know I haven’t abandoned him because I’m working my butt off on the phone trying to find a good place for him. I just feel so helpless.”

A recorded call with her care team in Dakota County summed up the dilemma. The county care coordinator told Kathy they hadn’t found a suitable place to place Preston.

Although she’d earlier advised Kathy not to bring Preston home and acknowledged the safety risk, now the county case manager said it was necessary.

Apologizing, the county worker said there was simply no other choice. “We are part of this whole service system which is not in good shape right now. It’s in bad shape and families are feeling the brunt of it.”

How did we get here?

The boarding problem is nothing new in Minnesota. The state has long lacked beds for teens experiencing mental health crises, and for more complex behavioral cases like Preston’s.

COVID exacerbated those deficiencies. Two large in-patient facilities in Minnesota shut their doors, eliminating around 100 beds between them. Mental and behavioral healthcare experienced extreme staffing shortages. Experts say years of shortchanging mental and behavioral health reached a breaking point.

Assistant Commissioner Gertrude Matemba-Mutasa with the Minnesota Department of Human Services acknowledges the crisis.

"When we look at Minnesota compared to other states, we don’t like where we are,” she told KARE 11.

Still, she said the state has been working for three years to build a system with earlier interventions so families in need get help before there’s a crisis.

“When we were thinking about solutions three years ago, we did not anticipate that we were going have a workforce shortage to this extent,” Matemba-Mutasa said.

She said the governor has asked lawmakers for $50 million for children’s mental and behavioral healthcare and to expand crisis beds.

Fairview says they are also investing in transitional services and facilities and will open more beds specifically for kids in crisis.

A temporary solution for Preston

After the care conference call, Preston’s parents had to find a new plan absent a facility or group home which could meet his needs.

His father, an active member of the military, took leave and returned to Minnesota to care for Preston in a house without other children where he could keep a constant eye on his son.

Weeks later, the family finally got Preston into another temporary crisis home.

A longer-term solution is still being sought. Kathy says in an ideal world, Preston would stabilize to the point he could safely return home.

She misses her son.

“I just tell him every time I see him, that I love him very much and we care about him and we miss him and we want him to come home. But we want him to be safe,” she said.

Watch more KARE 11 Investigates:

Watch all of the latest stories from our award-winning investigative team in our special YouTube playlist: