KARE 11 Investigates: Mentally ill, known to be dangerous, discharged anyway

Part 2 – “The Gap: failure to treat, failure to protect” reveals how dangerous holes in Minnesota’s mental health system cost a woman her life.

Neighbors made the 911 call to St. Paul police around midnight last year. They heard fighting between a man and woman in nearby apartment number 6. It sounded like it was getting physical.

It was getting worse.

The two officers who arrived heard a child wailing and a man screaming.

“Stay down or I will kill you,” he shouted.

By the time the cops could kick down the door it was too late.

Inside they found a 2-year-old boy covered in blood, standing next to a woman lying face down – 21-year-old Abigail Simpson, already dead.

Her boyfriend, 23-year-old Terrion Sherman, stood over them, also covered in blood.

A quick background check would show that Sherman already had a criminal history littered with charges including arson, assault, and robbery. In some of those cases, judges found him mentally incompetent to stand trial.

Officers soon realized the severity of Sherman’s mental illness. He told investigators that the boy – his nephew he and Simpson had been babysitting -- turned into a dog. It was self-defense, he told them, because Abigail turned into a dog and a man and came at him with a knife.

Sherman is known in Minnesota as a gap case – found incompetent to stand trial in previous charges due to mental illness, then released back into the community while still incompetent, often without the necessary help and support.

Chapter 1 Untreated and Dangerous

KARE 11 began investigating gap cases after the mass shooting and bombing at the Allina Crossroads Clinic in Buffalo last February.

Gregory Ulrich shot five people, killing one. He has been charged with murder and is awaiting trial.

About two years before the shooting, an Allina doctor obtained a restraining order against Ulrich after he threatened to shoot up one of the company’s hospitals or clinics. When Ulrich was accused of showing up at Allina’s Buffalo hospital, a prosecutor charged him with violating the restraining order.

But the prosecutor dismissed that charge after an evaluation found Ulrich incompetent to stand trial – incapable of assisting in his own defense.

Without any mental health treatment and no conviction on his record, Ulrich legally purchased the handgun he ultimately used in the clinic shooting.

Terrion Sherman was a different type of gap case, one created by the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS).

A year before Simpson’s murder, prosecutors charged Sherman with assault and aggravated robbery. A judge found him incompetent to stand trial.

But unlike Ulrich’s case, a judge considered Sherman such a threat to himself or others that in October 2018 he ordered Sherman to get treatment by civilly committing him to DHS. Commitment orders are the only way for Minnesota courts to mandate the mentally ill get treatment.

Records show Sherman went to the “Competency Restoration Program” at St. Peter State Hospital to treat his mental illness so he could return to court to face trial.

Then, two months later in December 2018 – without any warning or input from the courts or counties – DHS made public a major policy change it had quietly been doing behind the scenes for much of that year.

DHS announced it would stop providing competency restoration to patients charged with crimes who the agency determined no longer need hospital care. Instead, DHS would “provisionally discharge” them back into the community.

Once discharged, DHS no longer provides care or oversight for the patients, instead transferring that responsibility back to the counties that committed the defendants.

At the time, Bill Ward, Minnesota’s chief public defender, criticized the decision. “By not seeking input from stakeholders, all DHS accomplished is to wipe their hands of their concerns and turn a blind eye as to what will result,” Ward wrote in a letter to Gov. Tim Walz.

Chapter 2 Defending the Discharges

DHS defends provisional discharges, saying that defendants who needed competency restoration were taking up limited bed space from patients who needed more intensive care.

As the agency put it in a slide presentation, to treat more patients, they had to discharge more patients.

“We simply did not have the capacity,” said Dr. KyleeAnn Stevens, DHS’ chief medical officer.

What’s more, Stevens says competency restoration was never DHS’ job in the first place. There is no law in Minnesota that requires the agency - or anyone else - to restore criminal defendants to competency.

Judges tell KARE 11 the change in DHS’ policy created a new gap in the system.

“It’s very easy with large systems in government to think you’ve solved one problem and create a whole new set of problems,” said Dakota County Judge Kathryn Messerich. “And I think that’s what happened here.”

When a defendant is provisionally discharged while still incompetent, judges can’t legally put them back in jails that don’t provide competency restoration programs.

Judges, Messerich said, don’t have the authority to do anything else but let them go.

Since making its announcement, DHS said it has provisionally discharged 665 patients – including Terrion Sherman. The agency said it does not track how many of those were incompetent when discharged.

Records show about a third of those provisionally discharged went to jails, while the majority went to unlocked places in the community such as treatment services, adult foster cares, group homes or even their own homes.

In a letter sent to judges, prosecutors, county administrators and other stakeholders in December 2018, then-DHS Commissioner Emily Piper wrote that the change to provisional discharges started with a pilot project in 2017 and “no problems related to this change have been reported.”

Since then, however, KARE 11 has documented dozens of cases where provisionally charged defendants went on to commit more crimes. Some minor, such as trespassing, drug possession, theft or making violent threats. Others far more serious, including domestic assault, stabbings, beatings and, like Sherman, murder.

DHS’s Stevens says there is no connection between the agency’s change in provisional discharges and the crimes defendants committed after they were released.

“We provide treatment and appropriate after-care planning with county collaboration before we entertain a provisional discharge,” Stevens said. “If we feel there is not a provisional discharge plan that is safe for the individual or for the community, we’re not going to pursue that plan.”

That apparently included Sherman.

Chapter 3 A Failure to Treat

A review of hundreds of pages of Sherman’s case records shows how his provisional discharge to a group home in May 2019 resulted in a long list of failures to properly treat him.

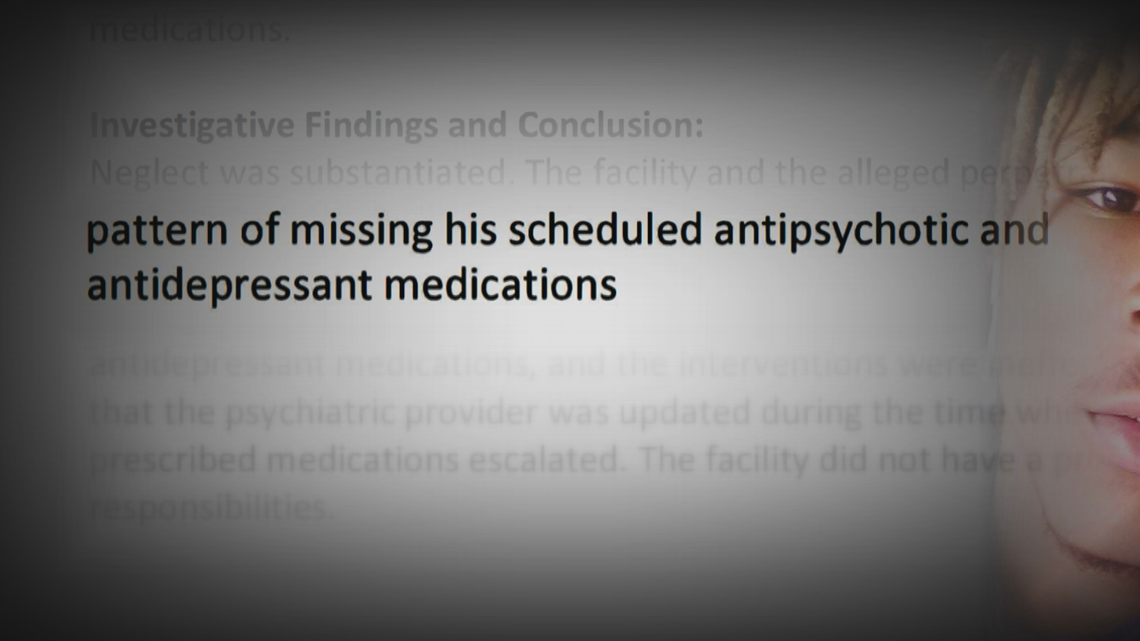

He came and went as he pleased from the home. He went for days – sometimes weeks – without taking his medications. In all, records show he missed his daily medications 76 times in just eight months.

He was even arrested, accused of fleeing Metro Transit police who say they spotted him dealing drugs.

Despite that, no one revoked his provisional discharge.

He wasn’t sent back to the state hospital until after police found him standing over his girlfriend laying in a pool of blood as his 2-year-old nephew screamed in horror.

What Abigail went through that night haunts her family.

“That was one of the hardest things our entire family deals with,” said her mother, Michelle. “Just how scared she must have been. She was beaten and stabbed. A lot.”

“Our hope is that she didn’t suffer very much.”

Chapter 4 'She Cared for Him'

Sherman’s mother died when he was 11, leaving him no structure or stability, said his sister, Janel Sims. “He became a prodigy of the streets,” she said. “All he knew was my mom. When she left us, all of us got messed up in the head.”

By 17, Sherman had already been charged with robbery, terroristic threats and third-degree assault – though all of those charges would be dismissed.

At 20, he faced first degree robbery charges when he provoked an argument with a stranger on a metro train, and with a friend stole the man’s cell phone. Security video shows he viciously stomped the stranger in the head. He was convicted of theft as part of a plea bargain.

The next year, in 2018, he met Abigail Simpson, who moved to St. Paul for treatment at Hazelden. She grew up in the Milwaukee suburb of West Bend, developing an addiction to alcohol and pot.

“When she developed substance use disorder and entered recovery, she became even more compassionate and empathetic,” her mother Michelle said.

The two started dating soon after they met.

“She cared for him very much,” Michelle said.

After Simpson went home in June 2018, Sherman’s troubles continued. He triggered a manhunt in Maplewood that August after trying to break into cars and starting brush fires, records show. He told police he smoked K2 – a synthetic marijuana -- and heard voices.

Sherman was arrested again that month after he tried to get into a neighbor’s apartment, then lit his shoe on fire on a grill, according to the criminal charges. He told police he smoked K2 and needed to go to the hospital. Once there, he was accused of spitting on an officer and emergency room technician.

Less than two weeks later he was accused of robbing a Family Dollar store and repeatedly punching two clerks in the head.

Facing charges in those cases, a Ramsey County judge found him incompetent to stand trial in October 2018 due to mental illness, putting the charges on hold until he could be restored to competency. A week later another judge ordered Sherman committed to DHS and sent to Minnesota State Security Hospital in St. Peter for competency restoration.

Following another evaluation in March 2019, a judge found Sherman still incompetent to stand trial.

But two months later, in May 2019, DHS “provisionally discharged” him to “Joyful Home Health Care,” a Fridley group home.

Sherman said in a recent interview with KARE 11 that he should have been kept at St. Peter.

“I was still ill,” he said.

Chapter 5 'Not a Locked Facility'

It wouldn’t take long for Sherman to get into trouble after his provisional discharge. Police arrested him in June at a gas station after a clerk caught him shoplifting.

He missed taking his anti-psychotic and anti-depressant medications seven days in July and continued leaving the home without approval, prompting a worker at the group home to alert a Ramsey County case manager who had taken over Sherman’s case.

“It’s also a violation of his commitment order, which could result in return to hospital or jail – which of course we’d want to avoid!” the case manager replied.

Eventually Sherman returned to the home.

“Can you and your staff strongly remind him to stay there?” the case manager wrote, underlining strongly.

Sherman didn’t listen.

He took off for days. When staff called him, he told them he’d come back, but didn’t.

One of the staff members would later tell a state health department investigator that they could do little to stop him.

“She stated it is not a locked facility, and staff could not stop the client from going on outings,” according to a health department report.

He missed his medications seven days that August, when Abigail moved back to St. Paul to go to school and be with Sherman.

He missed his meds another eleven days in September.

When they couldn’t find Sherman, staff resorted to texting Abigail, warning her of the consequences of Sherman being unsupervised and not taking his meds.

Joyful Home administrator Adetomi Omotayo declined to comment for this story. Ramsey County also declined to comment on Sherman’s case.

He seemed to get back on track in October, taking his medications each day. But he relapsed in November, missing his meds another six days.

It got worse in December, when he missed 16 days – half the month.

Police arrested him mid-December when they spotted him selling drugs at a Metro Transit station in downtown St. Paul about 15 miles away from Joyful Home, according to court records. He would go from the Ramsey County jail to Washington County’s, where he was booked on an outstanding warrant for violating the conditions of his release in an earlier drug case.

Joyful Home staff again emailed the Ramsey County case manager, saying they could no longer care for Sherman.

“The home is not sure how to help (Sherman) if (he) can’t make himself available for the service to be provided,” a staff member wrote in the email.

The county had the power to recommend that a judge revoke his provisional discharge and send him back to St. Peter. Instead, his case manager held an emergency meeting with Sherman at Joyful Home in January, telling him that jeopardizing his placement there “may not be such a good idea,” according to case records.

“I want to still live here,” he told them.

They drew up a contract with him, allowing leaves of absence twice a week so long as he adhered to the rules of the home. An entry in Sherman’s case file noted, “In principle … he agreed to the terms of the contract.”

But records show he missed his medications another 22 days in January and another 7 in February.

Sherman went back to court on February 20 – just days before Abigail’s murder. A judge ordered medications forced on Sherman if necessary, and had him recommitted to DHS, “subject to (Sherman’s) provisional discharge.”

That kept him at Joyful Home, where on February 25th he told a staff member that he and another resident were going to go to a nearby gas station. The staffer would later write in her notes that Sherman appeared delusional. She encouraged him to stay. Another staff member told him to bring his medication, but he said he’d be back for it.

Instead, the other resident came back to the group home and told them that Sherman ran off.

He would meet up with Abigail. Later that night the two picked up his nephew and brought the little boy back to her apartment. They told his mother they wanted to take him to breakfast the next morning.

When they returned to the apartment, a neighbor would tell police he heard Abigail and Sherman yelling. Abigail screamed “Stop.” Before police could get there, he heard Sherman throw her around the apartment. Another neighbor said he heard Sherman beat her.

In addition to blunt force trauma, an autopsy found Abigail had been stabbed multiple times in the head and neck.

Police took Sherman to a hospital, where he was diagnosed with drug induced psychoses.

After prosecutors charged him with murder, a judge found him incompetent to stand trial and sent him back to St. Peter.

After more than a year in treatment, Ramsey County prosecutors argue Sherman is now competent and his murder trial should proceed.

Chapter 6 Pleading for Change

Tom and Michelle Simpson said they knew something was wrong the day Abigail died before police ever came to their door. Abigail didn’t call like she normally did. Her mom called her without an answer. She called her work, but Abigail didn’t show. Michelle had a terrible feeling. She googled “St. Paul crime” and saw pictures of Abigail’s apartment building surrounded with crime scene tape.

A few weeks later as her parents were going through Abigail’s belongings from her apartment, they found records that showed Sherman’s civil commitment for being mentally ill. As they dug deeper, they discovered that Sherman had been released from St. Peter to a group home that wasn’t locked. They learned that only a few days before Abigail’s murder the court ordered continued treatment and authorized medications forced on him.

It raised so many questions: Was his placement at Joyful Home appropriate? Did they provide him with the needed care? And why, despite repeated violations of his treatment plan, wasn’t he sent back to the state hospital?

Michelle filed a complaint with the Minnesota Department of Health, which found both Sherman’s care provider and the facility itself responsible for neglect.

It wasn’t just Joyful Home that failed, the Simpsons say. It was also the courts, DHS, and Ramsey County that allowed a mentally ill man to fall through the gaps in a system that should have protected people like Sherman and Abigail.

Now they’re pleading for that system to change.

“Ensure that people are receiving the mental healthcare that they’re supposed to be receiving so they don’t cause harm to themselves or other people,” Michelle said. “Do it as if their child’s life depended on it.”