KARE 11 Investigates: Minnesota’s justice system has failed kids and the public

More than 150 teens charged with violent crimes are re-offenders, KARE 11 found, despite a system that is supposed to protect the public and help kids.

Jalen Watts again sat behind the wheel of a stolen car, this time driving through St. Paul when he and a friend saw 17-year-old Dede Jackson, an acquaintance from school.

She grew up in poverty, pulling herself and her younger siblings up through the foster care system.

Jalen also grew up in poverty, homeless for a time and often surrounded by violence. “A product of his environment,” said Schvonna West, who raised him as a single mother.

She tried in vain to keep him out of trouble. She knew where criminals go – “prison or the grave,” she said. But by age 17, when Jalen spotted Dede, he already had years of history in the juvenile justice system for gun possession, stealing cars, and fleeing police.

Whatever the courts threw at him – juvenile detention, therapy, mentoring, out of home placement – all failed.

That day in April 2020, Dede was with two other girls when Jalen asked them if they wanted to go for a ride. Not knowing the car was stolen, they said yes.

Then while driving, Jalen saw a cop. He floored the gas pedal, hitting up to 88 mph on a city street before losing control and slamming into a tree, slicing the front of the car in half.

Police found Dede, who had been sitting in the back of the car, with her head almost wedged underneath the front seat.

A few days later, Dede was declared brain dead.

Jalen would go home from the hospital the next day. As police investigated his case, records show, he committed more crimes, including a carjacking and a home invasion.

The courts tried another intervention – sending him to a juvenile prison. But after he got out, police say they found Jalen trying to ditch a loaded handgun.

He’s now in jail facing several years in an adult prison if convicted.

By law, Minnesota’s juvenile justice system is supposed to protect people like Dede and rehabilitate kids like Jalen.

“The system failed,” said Dede’s mother, Natasha. “It failed Dede. But somewhere along the line it failed Jalen, too.”

“And that failure caused my daughter to die,” she said.

That system not only failed those two, but hundreds of others, a KARE 11 investigation has found.

Repeat Offenders

Jalen’s case is just one example of a wave of high-profile crimes since 2019 – many involving juveniles – leaving the Twin Cities on edge. Gun crimes, carjackings, home invasions and murders have spread from the inner cities to the suburbs, prompting outcry from the public and politicians.

In Minneapolis alone, records show overall reports of violent crime – including homicides, robberies, aggravated assaults and vehicle thefts – rose 45% between 2019 and 2021. Although the Minneapolis data doesn’t specify how many reported crimes involved kids, the Hennepin County Attorney’s office says juveniles have been involved in twice as many carjacking cases than adults.

Yet as legislators debate reforms at the state capitol and community members demand accountability, they are often operating in the dark, with little known about how well the juvenile justice system operates. By design, the system gives limited information on juveniles so their mistakes as kids don’t follow them as adults.

The public is also operating without an answer to a crucial question: How often are the juveniles accused of committing serious crimes these last few years repeat offenders?

As KARE 11 learned, no state agency has tracked that vital information.

To do what the state has not, KARE 11 reviewed thousands of pages of criminal charges, court records and police reports to build a database focused on juvenile recidivism.

Although most juvenile records are sealed, cases against teens at least 16 years old are public. Charging and sentencing documents in those cases often reference prior crimes.

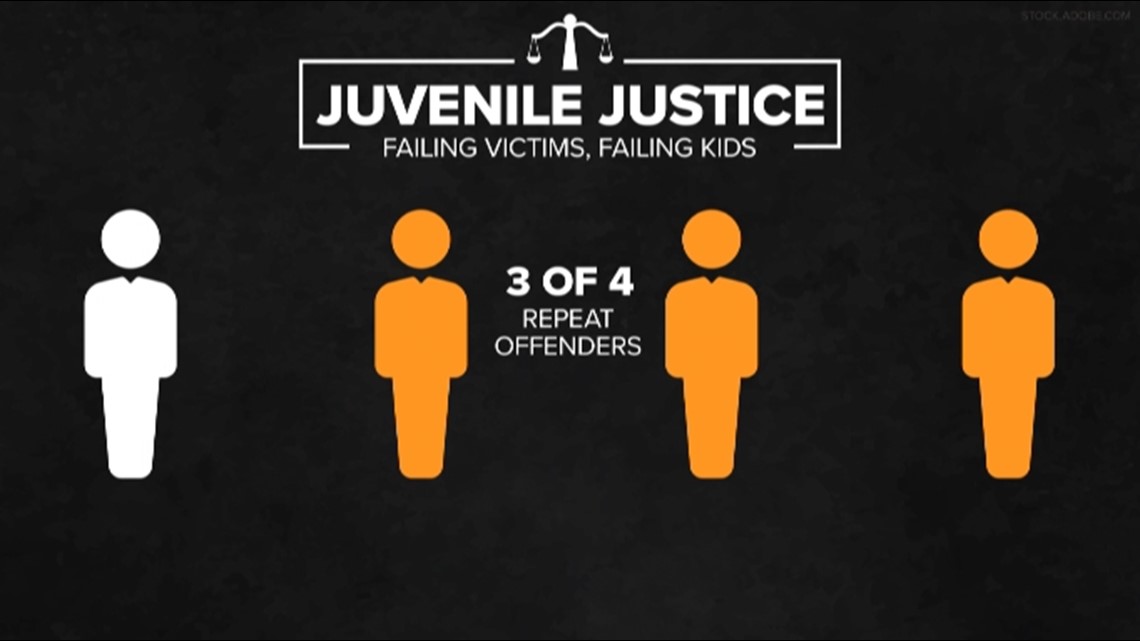

The results: We found more than 205 juveniles since 2020 charged in the metro area with such serious and violent crimes that, if they were convicted as adults, they would be facing presumed prison sentences.

Of those, 151 were repeat offenders – or about three out of every four.

Despite a justice system that is supposed to be protecting the public, those repeat offenders have been accused of hundreds of crimes. Seventeen of those juveniles have been charged with murder or homicide.

Meanwhile, a system that is supposed to rehabilitate kids and prevent them from being institutionalized has instead seen nearly 70 cases where the juveniles are already in prison, or facing charges where prison is all-but certain if convicted.

'They tap them on the wrist'

There is no one reason for those failures. As KARE 11 reviewed the juveniles’ case histories and interviewed parents, patterns emerged.

The kids often experienced foster care, severe trauma, poverty, neglect and abuse as young children, sometimes while being raised by parents who themselves had significant criminal pasts. Some have seen their friends murdered.

“Things that have happened to those juveniles that I think for most people you can’t even really imagine in terms of trauma that they’ve experienced,” said Mark Ireland, the presiding judge for Ramsey County Court’s Juvenile and Family Division.

Ireland believes early interventions and better support for children and families at risk is vital.

“When they enter the juvenile justice system, the needs are incredibly complex. And it’s not something that I think the juvenile justice system is going to quote unquote ‘fix.’”

It’s why Catherine Johnson, director of Hennepin County’s Department of Community Corrections and Rehabilitation, also believes support for kids and their families need to start much earlier.

“I think we’re missing resources and tools at the front end before kids ever get involved in behavior that is criminal,” Johnson said.

We also found failed placements, treatments and interventions. When kids got back onto the streets, probation failed to supervise and help them stay out of trouble.

To Schvonna West, Jalen’s mom, there’s another reason. She thinks the system wasn’t hard enough on her son when he first started committing crimes as a young teen.

“They tap them on the wrist, and they shouldn’t,” she said.

That leniency leads to juveniles who think they can get away with crimes, said Crystal Police Chief Stephanie Revering.

“We continue to arrest, and nothing happens,” said Revering, who as president of the Hennepin Chiefs of Police Association has been advocating for reforms.

“Do I want a 16-year-old kid to spend the next 10 years of their life in prison because of a mistake they made? Absolutely not,” Revering said. “Do I think we need to come up with a different mechanism of how it is that we treat juveniles in the system? Yes.”

'No switching him'

Jalen was always a skinny, short kid, even now standing at only 5-foot-4. Schvonna remembers the first time her son got into trouble was in the first grade, when he brought a knife to school to defend himself from bullies.

When she lost her job and they became homeless, Schvonna said her son started hanging out with the wrong crowd, used drugs and drank. He was first arrested around age 13, when she said he and friends broke into a junkyard and started driving cars around.

She says she tried to steer him in a different direction, but in a neighborhood scarred by violence and with few supports – she felt helpless.

She said at around age 15, he started carrying guns for self-protection after he was shot at.

At 16, he stole a van and crashed it into two cars as he tried to get away from the police. Two days later he got out of juvenile detention. The next month he stole a gun from his aunt’s house and fired it in a St. Paul neighborhood, according to police and court records.

A Ramsey County judge sent him for a six-month stay at Boys Totem Town, a now-closed juvenile facility. His mother said he continued to abuse drugs there.

“They lock ‘em up … And they have groups, and they talk good, and they sound like they’re going to come out and be on a different path, “Schvonna said. “But they get out here and reality smacks them in face.”

That reality?

“We’re poor,” she said. “We come from a poor environment.”

“He was happy to be out, but he still wanted to be around the same kids doing the same thing. It was like no switching him,” she added.

About two weeks after getting out of Totem Town, police caught him and two others driving in a stolen car, according to court records. After fleeing police and crashing, Jalen ran and was caught by a K-9. A judge kept him on probation and ordered him to go to a community mentoring program.

That seemed to work for a time. But when the program ended, Schvonna said he went back to making money on the streets.

“I couldn’t keep him locked in his bedroom,” she said.

Sometime before the crash in April 2020, Schvonna remembers Jalen coming into her room one night, telling his mom he needed to talk.

“What’s going on, kid?” she asked.

“I don’t feel like I’m going to be here much longer,” he answered.

“What do you mean?” she said.

“I feel like I’m going to die soon or I’m going to prison for a long time,” he told her.

Given numerous second chances by the juvenile system, Jalen was about to do something that would cost a young woman her life.

'I love you'

Hours before the crash on April 27, 2020, Natasha O’Keefe remembers her daughter Dede being full of life.

“Happy and ready to conquer the world,” Natasha said.

It wasn’t always like that for her. Dede and her siblings grew up poor and needed to go into foster care several years ago. They turned to Natasha and her husband, a distant relative of the family, who had watched the kids grow up.

She was a strong-willed ‘A’ student, with a goal of being an attorney to help other foster kids go through the system.

“She was a caregiver,” Natasha said.

That day, Dede wanted to go out with two friends and walk around downtown. Natasha told them not to get into any cars with anyone and to be safe. If plans changed, she told them to call her right away.

“I gave them the mom talk,” she said. “And then it was ‘I love you.’”

She was only in the car for about 10 minutes before Jalen crashed it.

Police called Natasha, telling her to get to a St. Paul hospital. When she got there, doctors told her Dede’s neck was broken. She couldn’t breathe on her own.

Dede got worse as the days went on. A test revealed she was brain dead. The family was able to do an adoption for Dede and her siblings at her bedside before they were forced to say goodbye.

The day before her funeral, Natasha said she got a letter from Hamline University accepting Dede into post-secondary classes to go toward her dreams of becoming a lawyer.

After the crash, police found Jalen in the driver’s seat with his legs pinned under the steering wheel. Despite other passengers saying he was the driver, it would take more than three months for St. Paul police to submit the case and prosecutors to charge it, records show.

By then, Jalen was still using drugs, according to court records. In early August, he and his friends carjacked a man in St. Paul. The next day, he was part of a group that broke into a pot dealer’s home and robbed him and his family at gun point, records show.

After he was arrested, Jalen told investigators he was “not scared of anything and not afraid of dying.”

A few months later, he admitted responsibility for Dede’s death, the carjacking and the home invasion in court.

Natasha wanted Jalen tried as an adult, hoping he would be sent to prison.

Instead, Ramsey County Judge Shawn Bartsh designated Jalen as an “Extended Jurisdiction Juvenile.” An “EJJ” case results in both a juvenile court sentence until the age of 21 and a stayed adult court sentence. If the teenager fails to satisfy conditions set by the juvenile court, the adult sentence can be imposed – sending the teen to prison.

As part of a plea agreement, a 93-month adult prison sentence was put on hold on the condition he not re-offend. Bartsh sent Jalen to Red Wing – a locked juvenile facility – for nearly nine months.

Although he was specifically prohibited from having firearms, a few days after he got out in August of 2021, Jalen was at the scene of a homicide where he fired a gun, according to court records.

His mother said Jalen had been shot at. Fearing for their safety, Schvonna fled the state with him to Indiana, where she grew up.

After he fled, Judge Bartsh issued a warrant for Jalen’s arrest.

On February 8, 2022, a cop spotted him back in Minnesota with a 14-year-old girl who was a missing runaway from Indiana. When officers tried to arrest him, he admitted running from police and tossing a loaded gun, according to the criminal charge.

He is now charged with illegal gun possession. Because of his history of violent crimes, he faces a five-year mandatory minimum prison sentence if convicted, in addition to the 93 months he was already facing.

As he awaits his next court appearance, Jalen, now 19, has been charged with nine felonies in the last four years. He has been on probation since at least December 2018. The courts twice sent him to out-of-home placements, including to a juvenile prison.

Schvonna believes the system failed her son.

“I don’t know what would have worked. I just feel like what they’re doing isn’t working. Period.”

MORE FROM KARE 11 INVESTIGATES:

MORE FROM KARE 11 INVESTIGATES IN THIS YOUTUBE PLAYLIST: