PLYMOUTH, Minnesota — Walking into the police station in July 2011, she could still feel the force of the massive man pinning her arms down only hours earlier.

“I was raped,” she told an officer.

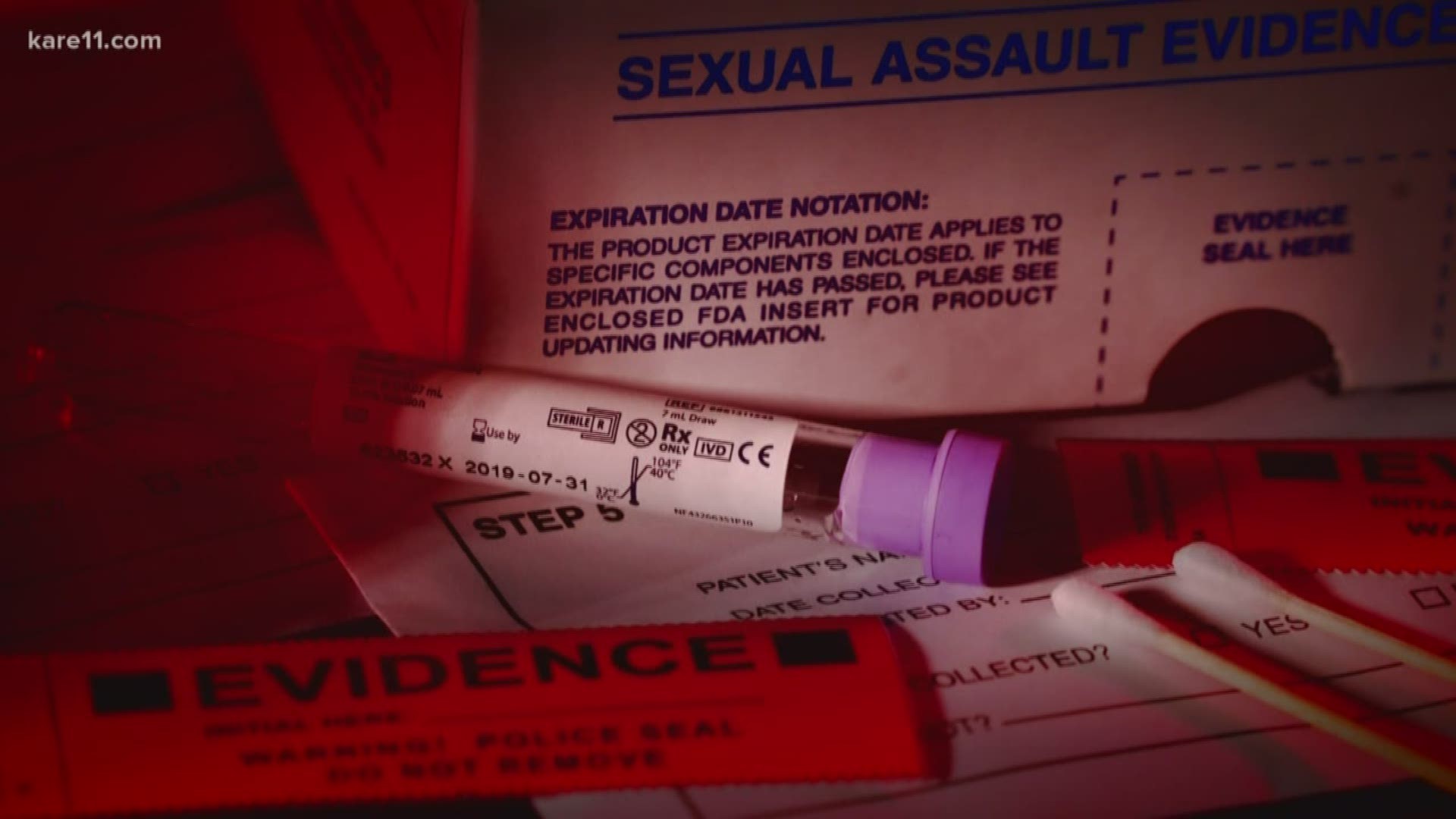

Police took her to a hospital where she underwent an hours-long sexual assault exam.

She tried to think about anything other than what was going on below her neck as strangers swabbed and examined her body.

It was an uncomfortable, humiliating experience, but one she thought would be worth it. Even though the suspect claimed the sex was consensual, she assumed the kit would be tested, and it would be used to bring the man to justice.

It was not until nine years later that she learned what actually happened with the kit. Not only did Plymouth police never send it to a lab for testing, they destroyed it, along with any hopes she had that the man could ever be arrested and charged in her case.

The same man, a former mixed martial arts fighter, would go on to batter and beat numerous other women, and now sits in a Colorado prison.

“They could have stopped him,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified. “But I went through all of that for nothing.”

“That is the worst feeling in the world.”

She’s not alone.

Minnesota’s destroyed rape kits

Even though Minnesota recently received a $2 million federal grant to DNA test the state’s backlog of thousands of untested rape kits, a KARE 11 investigation has found that more than 220 kits will never be tested because they’ve already been destroyed.

Overall, police agencies across the state destroyed more than 450 rape kits in unsolved and uncharged cases. Legal experts told KARE 11 it would be almost impossible to bring charges in a case involving a destroyed rape kit.

Regardless of whether it was tested, due to the wording in a state law passed 20 ago, KARE 11 discovered that destroying a rape kit likely starts the statute of limitations on when a case can be prosecuted. That can keep victims in the cases from ever seeing justice, even if new information surfaces.

“What you’re discovering is that these statutes of limitations are going to be a detriment to victims because somebody destroyed the kits,” said DFL Rep. Kelly Moller.

Far more kits have likely been destroyed. The findings come from KARE 11’s survey of 36 of the more than 400 law enforcement agencies in Minnesota.

The KARE 11 investigation also found:

- In 2017, the U.S. Department Justice recommended that rape kits in “uncharged or unsolved” cases be kept for at least 50 years. But Minnesota police departments have destroyed more than 200 kits from those types of cases since that time.

- In some cases, kits were destroyed only weeks after a case was reported.

- In other cases, the rape suspects went on to be convicted in different sexual or physical assaults. In one Brooklyn Center case, a man accused of rape was later charged twice with assault in Minnesota, and is now serving 45 years in an Illinois prison for attempted murder.

- There is nothing in the law that prevents police from destroying kits, or even requires that police DNA test them. A loophole allows police to opt out of testing a kit so long as they consult with a county attorney. A KARE 11 survey last year of about 20 departments found that one in 10 rape kits is still not being tested.

- Police destroyed more than 51 kits after deeming the case “unfounded” – meaning that the accusation was baseless and false. But the files in at least some of those cases show police often failed to do the investigation required to unfound a case but destroyed the kit anyway.

“I’m shocked, and nothing around the lines of sexual assault cases should shock me anymore,” said Rep. Moller, a prosecutor herself who has worked on sexual assault reform in the legislature. “It is very upsetting to know that these kits have been destroyed and really eliminating the chance for justice for these survivors.”

‘No excuse’

When it comes to untested rape kits, few agencies responded to requests for comment on why they destroyed them. Of those that did respond, they defended the practice, saying they most often did so in “consent” cases, where both the victim and suspect say that sexual activity occurred, but the suspect called it consensual.

“It’d be no benefit for sending in a kit for something like that,” said Chad Kleffman, a lieutenant with the Brainerd Police Department.

Brainerd reported 44 untested destroyed rape kits, the highest in the state among the departments KARE 11 surveyed.

But other police officials and victim advocates say the benefits to testing are two-fold: to not only affirm a victim’s experience of going through a grueling sexual assault exam, but more importantly so that DNA taken from the kit can be put into a federal database used to track serial offenders.

“One consent case could be a misunderstanding. Multiple consent cases could be a serial rapist,” said Rep. Marion O’Neill (R-Maple Lake).

“There’s just no excuse for destroying kits,” said Sgt. Richard Mankewich, who investigated thousands of sex crimes with the Orange County Sheriff’s Department in Orlando, Florida.

“It’d be like a murder taking place and you throw away the murder weapon,” he said.

Police departments across the country have used DNA from rape kits to catch serial offenders. That includes Duluth. A KARE 11 investigation last year found Duluth has charged and convicted predatory offenders after the department began testing its backlog of rape kits.

Law prevents charges

Those successes were only possible because Duluth kept its rape kits and did not destroy them.

State law says there’s no statute of limitations on prosecuting a sexual assault case that has been reported to police, so long as “physical evidence is collected and preserved that is capable of being tested for its DNA characteristics.”

However, if the evidence is “not collected or preserved,” the law says a case must be charged three to nine years after it was reported, depending on the victim’s age.

Because kits were destroyed, dozens of cases reviewed by KARE 11 likely can no longer be prosecuted.

KARE 11 consulted with more than a half dozen legal experts, prosecutors and defense attorneys alike, each of whom said that it appeared destroying a rape kit kicked in the statute of limitations.

Defense attorney Christa Groshek said if she got a case that involved a destroyed rape kit kicking in the statute of limitations, “I would look to dismiss that case.”

Another defense attorney, Ryan Pacyga, said if he had a case with a destroyed rape kit, he’d move to have it dismissed even if there was not a statute of limitations.

One reason Pacyga said he would want the rape kit preserved: so that the defense can run its own tests in a case. Destroying it, Pacyga said, could violate the due process rights of a suspect.

“Defense should have the opportunity to have that evidence re-examined to check for any errors,” Pacyga said.

At least one police chief said he'll change his department's practices.

In Bemidji, police chief Mike Martin said his department typically destroys tested kits in cases declined for prosecution. He said he was unaware that destroying a kit might trigger the statute of limitations, but after reviewing the law agreed that time to charge a case is triggered after a kit is destroyed.

“If there’s still a chance we could charge a case, we clearly wouldn’t want to destroy the kit,” he said.

Proposed reforms

Representatives Moller and O’Neill said they will introduce a bipartisan bill when the legislature returns next week that would effectively prevent police from destroying rape kits. Instead, it would require testing of all kits in cases reported to law enforcement.

They also want to create a tracking system that allows victims to see if their kits have been tested and if the DNA matches an offender.

Last year a KARE 11 investigation revealed that police were often failing to follow a state law that allowed victims to get information about their rape kits, leaving many in the dark about whether they were even tested.

In the meantime, Moller called on police to stop destroying rape kits.

“I know a lot of survivors, when they report, they report because not only do they want justice for themselves, but they want to be able to prevent this same perpetrator from doing the same thing to another survivor,” Moller said.

‘It just kills me’

That was the case for Michelle Johnson in Brainerd, who said she never knew her rape kit had been destroyed until she was contacted by KARE 11.

“Why are they not thinking of the bigger picture, you know, that it could help other people,” she said.

She was hanging out with a man she thought was a friend in her apartment in October 2014. She says she consented to a single sexual act, hoping he would stop pressuring her to have intercourse. When it was over, she says she tried to leave but he pushed her down onto her bed and raped her.

“He pinned me down and forced me,” she said. “And I told him no, I don’t want to do this.”

She went to get a rape kit a few hours later. The investigator on the case – Lt. Kleffman – called the suspect four days later and told him that the woman was accusing him of raping her. The suspect said the sex was consensual and agreed to come to the station for a formal interview, but records show he never showed. The suspect stopped returning Kleffman’s calls.

Kleffman sent the case to the Crow Wing County Attorney’s Office, which declined to charge it. The police department destroyed the kit in February 2018.

Kleffman said Brainerd Police often do not test kits in consent cases. Asked about testing the kits to see if they matched other DNA profiles in the federal database, he said he worried that testing every kit would only delay the already-months-long time it takes to get results back on evidence that is tested.

“It could make those delays even longer,” he said.

Most rape kits in Minnesota are tested by the state Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. Since 2015 the BCA says an increase in kit submissions has contributed to longer turnaround times.

“It used to be 45 days and now it averages 90 days,” a BCA spokesperson told KARE 11.

Johnson said she was heartbroken when she was told her kit had been destroyed.

“It just kills me to know that if he would ever do this to someone else, that they’re not going to have anything else out there,” she said.

‘A brick wall’

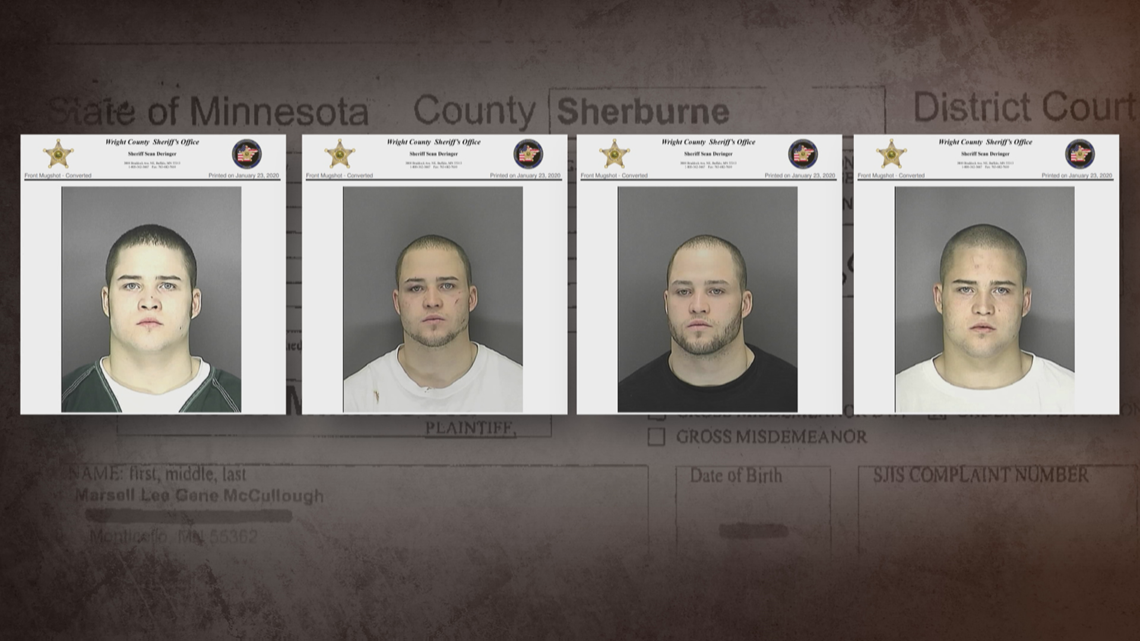

The woman who reported a rape to Plymouth police in 2011 was then a 21-year-old college student, accustomed to staying up all hours of the night working on projects. She met Marsell McCullough a few weeks earlier when she was on a date and he was a bouncer at a downtown Minneapolis night club. They discovered they had mutual friends.

He texted her a few weeks later and asked her to come over to his Plymouth townhome for a party late one night. Several of her friends from high school were there, he told her. But she quickly learned that wasn’t true when she walked in. The home was empty, save for one woman she didn’t know and McCullough, who was drunk.

She planned to go to the bathroom and then leave. She said McCullough walked into the bathroom and wouldn’t let her go. She says she tried to push his arm away as he tried to put his hand down her pants, but he was too strong.

McCullough was a 170-pound mixed martial arts fighter so muscular that the woman said McCullough couldn’t put his arms all the way down to the sides of his body.

“It was like fighting a brick wall,” she said. “He was just immovable.”

The other woman knocked on the door and said she was leaving. Now the student was alone with McCullough.

“Once that happened, there was nothing I could do,” she said.

She told police that he picked her up and took her to the bedroom.

She said she told him no several times and wanted to leave, but worried that if she fought back, given his size and strength, one punch could knock her out.

“I just waited until he was done,” she said.

She went to a friend’s home as soon as she left, who urged her to report what happened to police. Together they went to the Plymouth station, where she told her story before going to North Memorial Hospital.

She had watched enough crime shows to know that her body was now the key evidence to prove the case. She didn’t shower or even go to the bathroom before the rape exam.

“I thought I did everything right,” she said.

The next day a Plymouth police investigator called McCullough and told him he was being accused of rape. The detective urged McCullough to go to a hospital to provide a blood sample for an HIV test.

“No one was raped, no one was sexually assaulted,” McCullough told the officer, according to the police report.

McCullough agreed to provide a blood sample, but said he was two hours north of Minneapolis and didn’t drive. The detective offered to help – even drive to where he was, take him to Minneapolis for the test, then drive him back. McCullough declined. His blood was never taken.

Police tried to serve a search warrant on him at his home, but he wasn’t there, according to records.

McCullough would tell the investigator over the phone that the woman sent him a text the next day saying he never raped her. He said he’d show that to the detective, but never did.

When the detective called the woman about the text, she denied it and let police take pictures of her phone. She said that was the last time the police ever called her. She called occasionally to ask for an update on the case, but after a few months gave up.

According to the Plymouth police report, the investigator interviewed the other woman in the home that night, who offered little information other than to say it didn’t appear the accuser was in distress when she left the two at McCullough’s home.

Police sent the case to the Hennepin County Attorney’s office, which declined to prosecute. The department said the kit was destroyed, but did not know when.

Plymouth Deputy Chief Erik Fadden defended the decision to destroy the kit, saying testing it would not have made a difference in the case. He said it was declined due to lack of evidence that what happened that night was not consensual.

“Testing the kit was not going to tell us what we knew already,” he said. “That didn’t make or break this case.”

Since then, Plymouth’s policy has changed. He said for several years the department has sent in all kits for testing, and if the case had happened today, the kit would have been tested. The last time the department destroyed a kit was in 2015, according to records provided by the department.

The woman said after she stopped hearing from police, she decided to try put what happened that night out of her mind. She only held out faint hope that she might one day see justice.

Until she got a call from a KARE 11 reporter, she said she didn’t know her rape kit had never been tested and was destroyed.

She was also never told about McCullough’s violent criminal history, both before and after that night. When she accused him of rape, McCullough had been out of prison for three months and was on probation.

He was convicted of assault four times from 2007 to 2009, court records show, all in cases involving women. In one case in 2008, he was charged with beating two women in one night, including punching a woman in the face after she refused to have sex with him. The latter case was dropped as part of a plea deal.

When Plymouth police were trying to locate McCullough, records show he was spending part of his time behind bars for violating his probation in an earlier case. He served nearly two months for that. He also had a court appearance in another case. But there’s no record in the police file that investigators ever contacted his probation officer to ask about his whereabouts.

After he was released, McCullough was making public appearances at MMA fights in December 2011 in Maplewood and then in January 2012 in downtown Minneapolis. Even so, records show police investigating the Plymouth rape allegation never interviewed him face-to-face.

Two months later, McCullough was in Florida where records show he kicked and punched his girlfriend in a motel, then ran after police were called. When an officer caught him, McCullough punched him so hard it threw him to the ground. It would eventually take police dogs and a helicopter to catch McCullough. He was convicted of resisting an officer with violence and felony battery.

In early 2014 McCullough was back in Minnesota, where he was convicted of beating another girlfriend. He’d be sentenced to 21 months in prison for that case, getting out in 2015.

In October 2015 he was in Englewood, Colorado, with another girlfriend. According to the police report, he was driving through the city with the woman when he went into a rage, started beating her inside the car, then pulled her out of the car by her hair, and continued beating on her, breaking her arm. He ran, tried to break into a home to hide, then stole a car and fled from police. But he crashed and was arrested.

Convicted on multiple charges, McCullough has been in a Colorado prison since January 2017. He’s eligible for parole in September 2021 and has a mandatory release date of September 2028.

KARE 11 sent him a letter asking for his comment for this story, but he did not respond.

Plymouth police deputy chief Fadden said the department knew about McCullough’s background when investigating him for rape in 2011, but because his prior offenses were not sexual assaults, they would not have been useable in a criminal trial.

The woman who accused him of rape that night believes more could have been done. She wanted justice, but knows that’s impossible now due to her kit’s destruction and the statute of limitations.

She’s furious that rape kits like hers have been destroyed.

“It means hundreds and hundreds of people are out there where the person that raped them will never be forced to take responsibility for what they’ve done,” she said. “All because police couldn’t bother.”

Victims of sexual assault who need help are encouraged to go to www.rapehelpmn.org to find an advocate near them.

You can email reporter Brandon Stahl at bstahl@kare11.com. If you have a suggestion for an investigation, or want to blow the whistle on fraud or government waste, email us at: investigations@kare11.com