BEMIDJI, Minn. — Time after time while he was in the Beltrami County jail in 2018, Hardel Sherrell begged anyone who would listen to believe he was in excruciating pain and could no longer walk.

But his jail guards and medical providers repeatedly chastised the 27-year-old inmate, telling him he was faking and that he could walk if he just tried, even after Sherrell lost control of his bowels and bladder.

On the day he died, a guard told Sherrell as he sat in his own urine he could “get up and shower at any time,” records show.

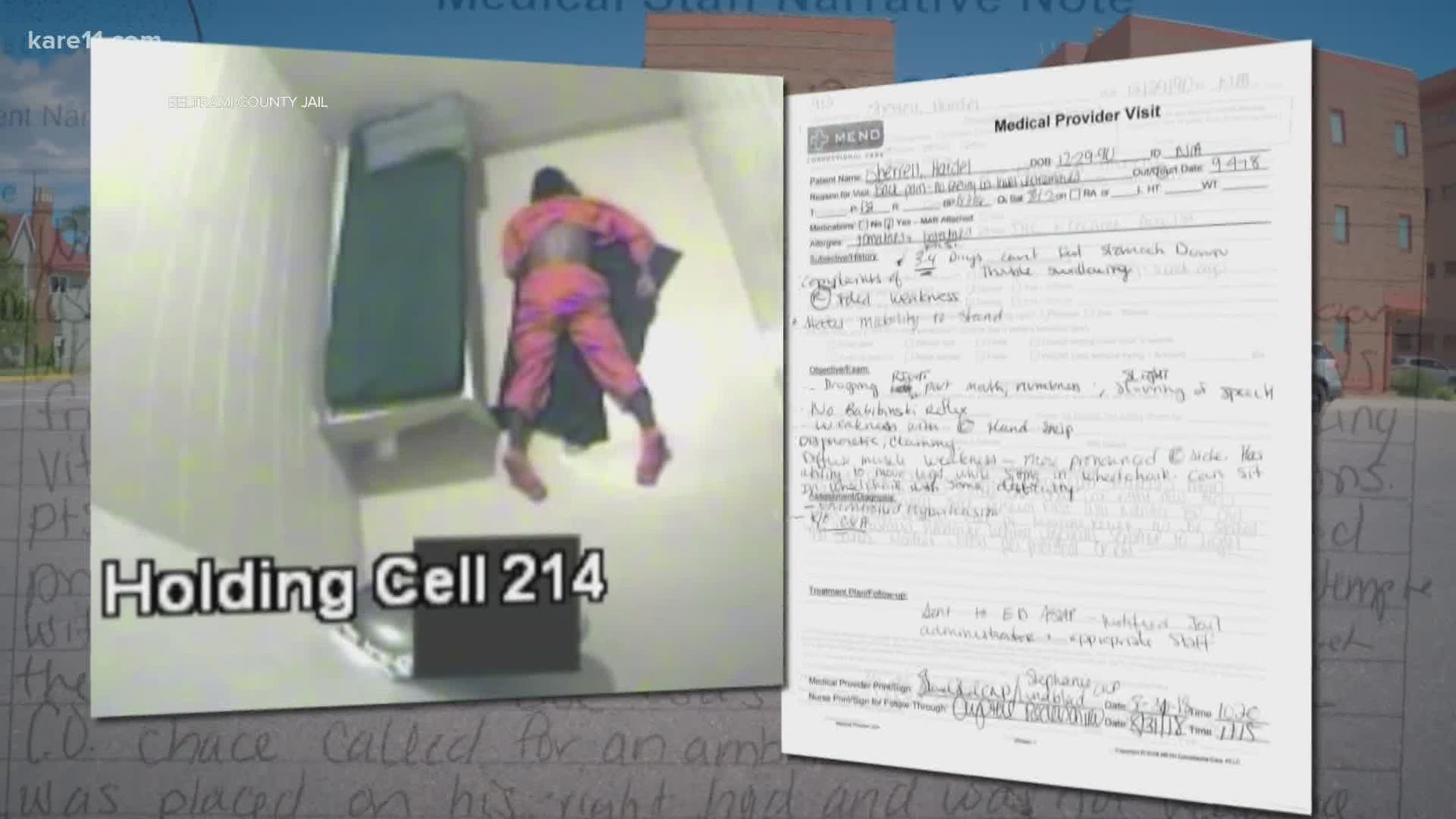

KARE 11 reviewed hundreds of pages of court and law enforcement records and hours of security video from the jail to construct a timeline in the days leading up to Sherrell’s death.

They reveal nearly all of his jailers and care providers dismissed his pleas for help and failed to follow up on numerous red flags that could have potentially saved him.

One of his care providers, a nurse who treated him three days before he died, believed Sherrell’s condition was deteriorating rapidly.

“One look at him and there was no doubt he was not faking,” the nurse, who asked not to be named, told KARE 11.

The nurse said what happened to Sherrell “haunts her.”

“Seeing what happened to George Floyd has just brought it all back,” she said.

‘Raised serious questions’

Records and interviews also suggest that initial investigations into the case were not handled properly or were never acted on.

A review by the Department of Corrections in 2018 found “no violations” in the case. Yet after Sherrell’s mother, Del Shea Perry, repeatedly and publicly raised questions about that investigation, another review released in May found “regular and gross violations of jail standards.”

“No other way to put it – stunning. When you look at the totality, it’s hard not to wonder how that happens,” Department of Corrections Commissioner Paul Schnell said after he watched video of Sherrell’s death.

An investigation into the case by Bemidji police was never sent to prosecutors for review, records and interviews show. But after watching the jail video, Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison sent a letter to the U.S. Attorney’s office asking for federal involvement in the investigation.

“It was disturbing, it raised serious questions that I felt warranted investigation,” Ellison said. Now, the FBI is investigating the case for potential charges.

The nurse who believed Hardel said a full investigation should have been launched long ago.

Just days after his death, the nurse sent whistleblower complaints about substandard care to the Department of Corrections and both the Minnesota Boards of Nursing and Medical Practice. Nearly two years has passed.

“I’ve been waiting for someone to just do something, anything,” she said.

“That information was provided two years ago almost, and as far as we know nothing is happening,” said attorney Zorislav Leyderman who represents Sherrell’s mother.

“Where is the action?” he asked.

Ruth Martinez, Executive Director of the Board of Medical Practice, told KARE 11 she is prohibited by statute from addressing specific complaints against doctors. But she added, “It is not out of the ordinary for an on-going investigation to take a lengthy period of time to resolve.”

‘The Truth’

On the day of Sherrell’s death, Beltrami County Sheriff Ernie Beitel, who was then the chief deputy, said in a press release that Sherrell died “from an unknown medical condition” and that he “collapsed and became unresponsive” in front of jail staff.

However, records and video show that Sherrell could not stand for days before he died.

A pathologist hired by Sherrell’s mother as part of a federal lawsuit she filed would later determine he died from Guillain-Barre Syndrome, a treatable condition that attacks the nervous system causing paralysis.

Leading a protest outside of MEnD’s Sartell headquarters last week, Perry accused the company and Beltrami County of covering up the truth about her son’s death. MEnD provides health care services for the Beltrami County jail and more than 30 others across Minnesota, Iowa and Wisconsin.

“Truth -- that’s all I’m fighting for, is the truth to be told,” Perry said.

Timeline of his death

Here’s what happened, according to records, interviews and jail security video:

Aug. 24, 2018:

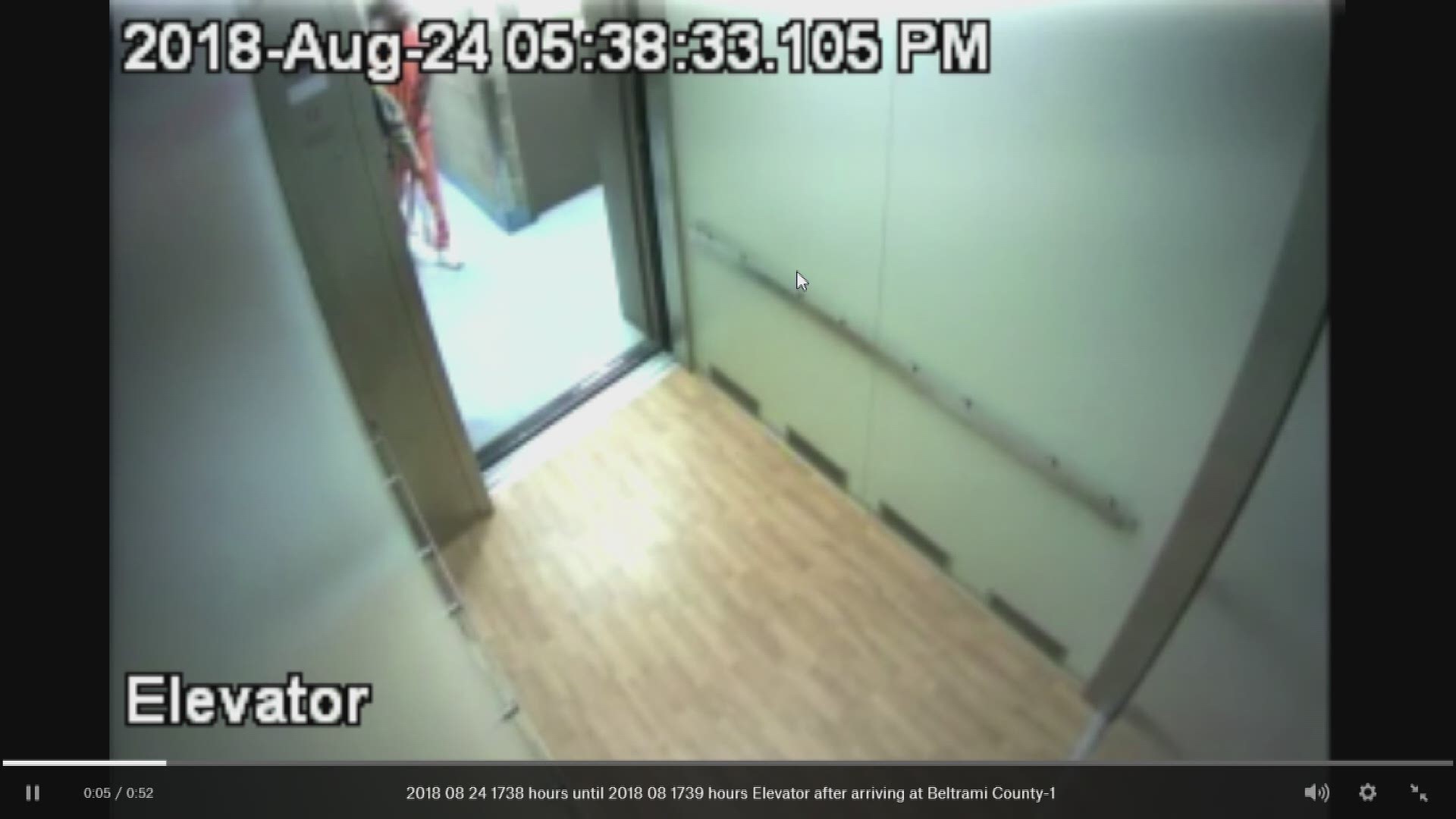

Sherrell is transferred from the Dakota County jail, where he had been charged with domestic assault, to Beltrami County to face charges of felon in possession of a firearm.

His mother, Del Shea Perry, said her son knew he was looking at several years in prison, but wanted to serve his time and turn his life around. “I’m not saying my son was perfect,” she said. “But he sure as heck wasn’t the devil and he wasn’t a monster as they treated him.”

Sherrell is seen on security video walking into the jail without problems and even joking around with one of the corrections officers in an elevator.

Aug. 27:

A MEnD nurse examines Sherrell after he complains of chest pains and headaches and says his hands are tingling.

An electrocardiogram test result is “abnormal” and shows probable inferior infarction – or heart damage. The physician in charge of MEnD, Dr. Todd Leonard, reviews the case off-site and orders over-the-counter pain killers and a prescription antihistamine for Sherrell.

Aug. 28, Morning:

Sherrell falls off his bed and lays on the floor for 25 minutes until his cellmates lift him back. He sees a MEnD nurse, who notes that he’s crying and complaining of back pain and right arm weakness.

Aug. 28, Evening:

Sherrell writes a request for medical care to jail staff, saying he needs to be taken to the hospital because he cannot feel his legs and be physically mobile. “Please be fast about this because I’m in incruciating [sic] pain in all my muscles all over my body,” he wrote.

In her notes, a MEnD nurse writes that he again has an elevated blood pressure. But she apparently suspects he was faking other symptoms, noting that staff told her “He was just standing and holding phone previously this am.”

Aug. 29, Morning:

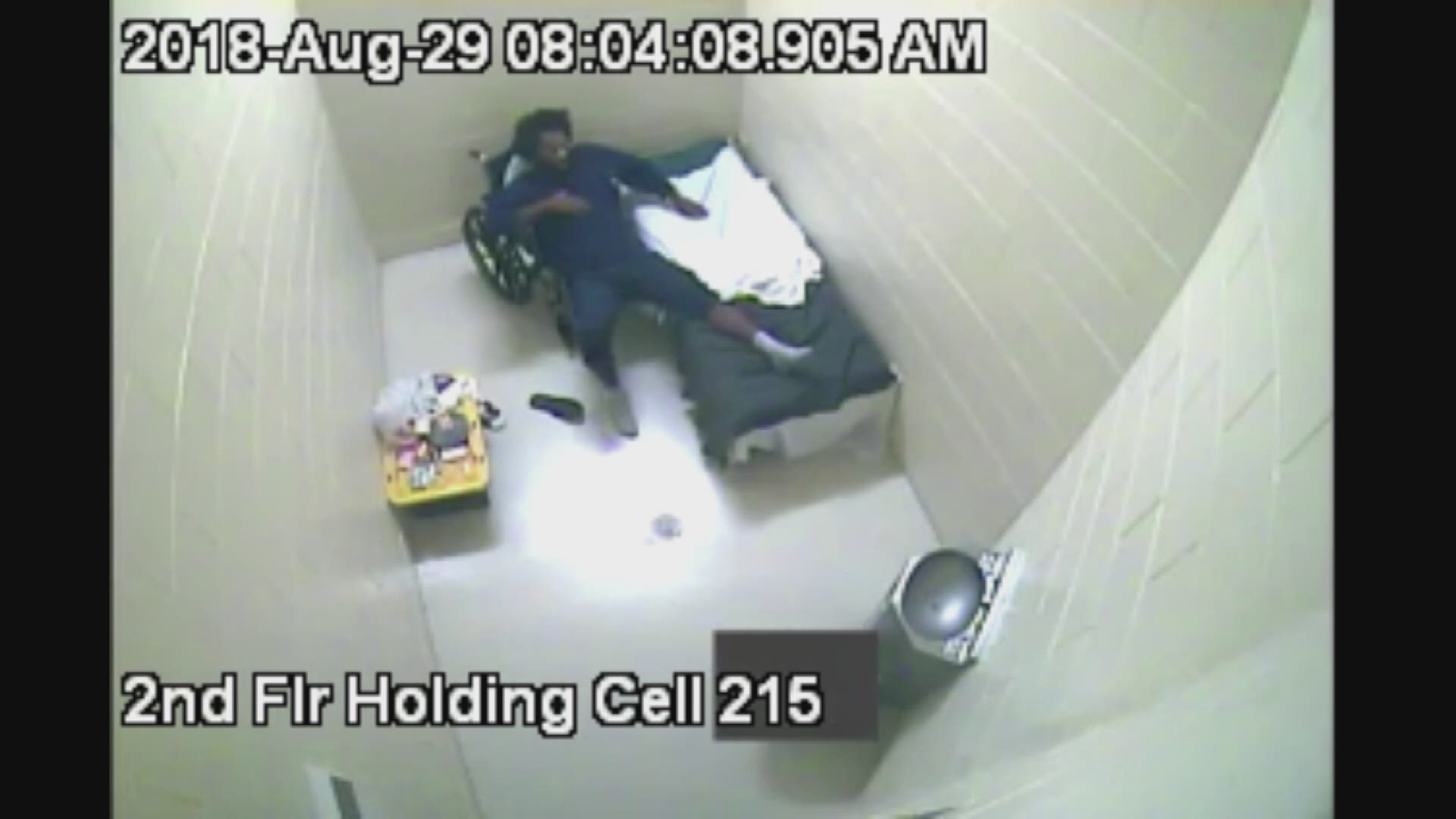

Sherrell says that he “cannot feel his legs or be physically mobile” and his pain is getting worse. He is moved into a segregated room.

Aug. 29,

Sherrell asks for a wheelchair so he can be closer to a toilet. Later video shows him falling out of the wheelchair onto the floor.

Aug. 30, morning:

Sherrell tells the MEnD nurse that he can no longer feel anything from the waist down and he urinated on himself.

After getting an update from a nurse, Dr. Leonard advises sending Sherrell to the ER. But jail administrator Calandra Allen vetoes that, saying Sherrell was a flight risk. "Patient has been seen using his arms and legs with no difficulty," the nurse writes.

Aug. 31, Morning:

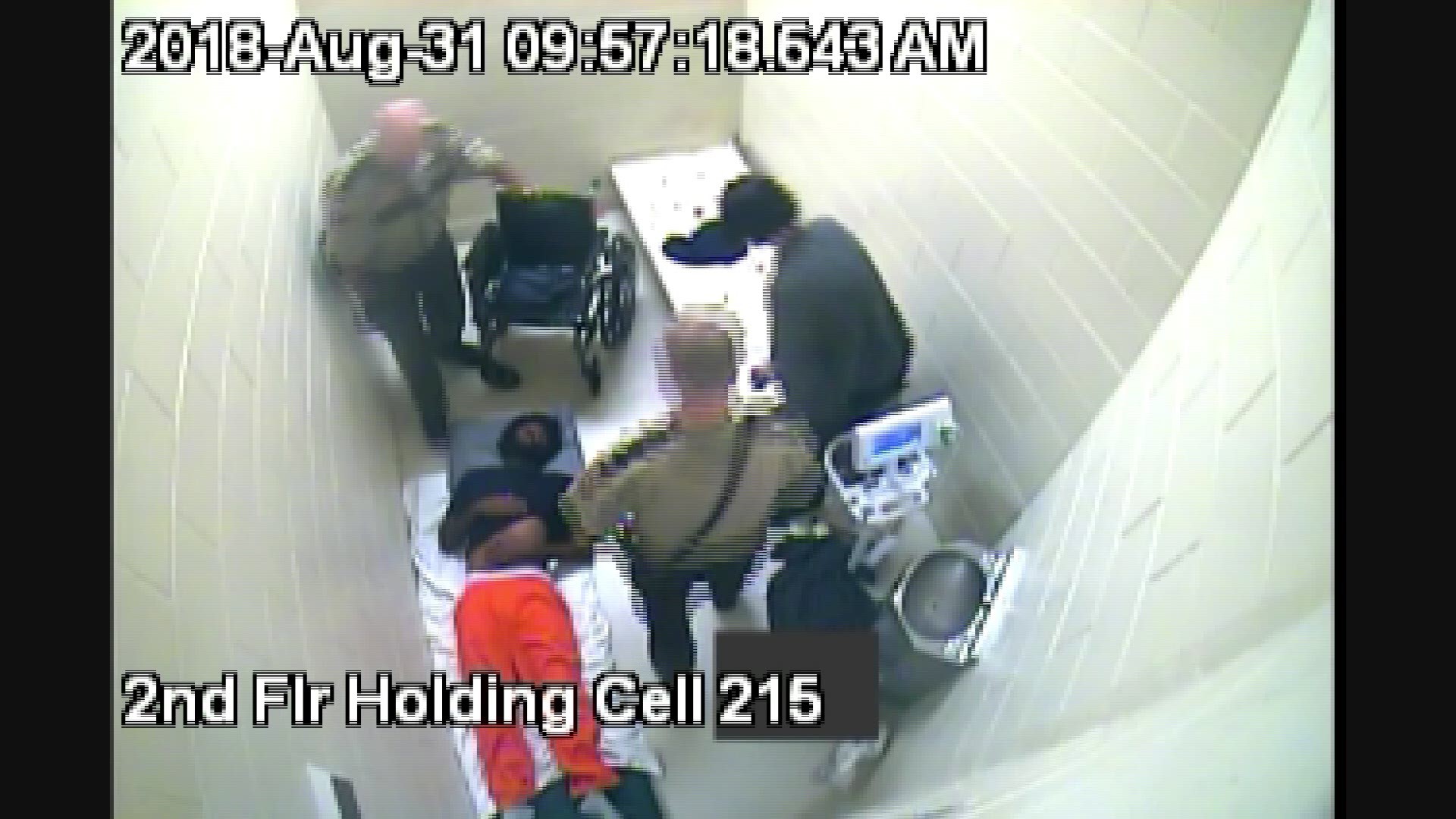

A different MEnD nurse visits Sherrell, finding him in “disturbing” condition. She is overwhelmed by the stench of urine in the room. He was wearing a soiled adult diaper, which was soaking the mattress pad underneath him.

He had no reflex when his foot was rubbed and his body was cold even though he was sweating. He tells the nurse he can’t eat because there’s something wrong with his swallowing.

“He looked at me and asked me to please believe him that something was wrong,” she would later write. “He had tears running down his eyes when he pleaded with me to get him help.”

Concerned he had a stroke, she directs that Sherrell be sent to the ER immediately.

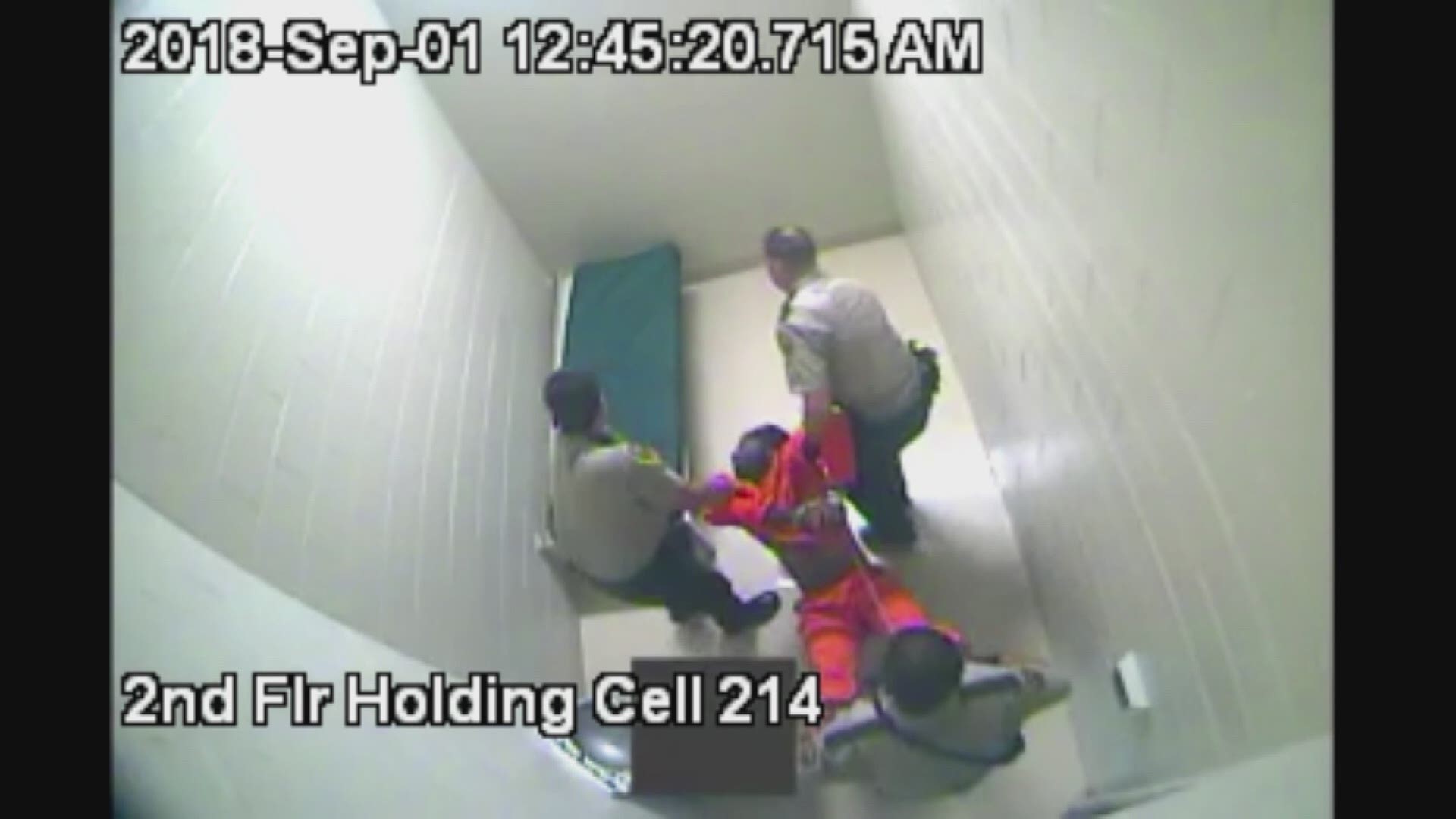

As she and another nurse put clothes on him to send him to the hospital, she said “Hardel was crying out in pain.” Jail video shows it takes two correctional officers to lift him off the floor and into a wheelchair.

Aug. 31, Evening:

At the Sanford Hospital in Fargo, a guard said that he watched a doctor poke Sherrell’s legs with a needle, but “Sherrell never moved or acknowledged the needle pokes.”

A corrections guard reported that after an MRI, a doctor came into the room and said Sherrell’s MRI came back normal and that the doctor “believes the only reason he can’t move is because he isn’t willing to try.”

His discharge instructions diagnose him with fatigue and weakness, but do not identify an underlying cause.

In all caps, the Sanford discharge instructions state he should seek medical attention “IMMEDIATELY” if he experienced worsening weakness, difficulty standing, paralysis or loss of control of his bladder or bowels, or difficulty swallowing.

Despite those orders, and the fact that he will soon seem to meet every single one of those conditions, Sherrell will never see a doctor again.

Sept. 1

Early morning: Arriving back at the jail sally port, Sherrell tries to get out of the vehicle by himself but “he went limp and dropped his body weight causing himself to fall down.” They have to carry him back to his cell.

Later that day, a MEnD nurse tells Sherrell that “there was nothing wrong with him” and that he “could get up and walk if he wanted to.”

Mid-afternoon: A guard tries to help Sherrell use the bathroom and feed him but became frustrated. “I was done helping him if he wasn’t going to help me with him, and I exited the cell.”

Evening: Guards laid Sherrell down on the floor after being unable to sit him into a wheelchair. He is told that he cannot take his medicine unless he sits up. “Inmate Sherrell shook his head in response.”

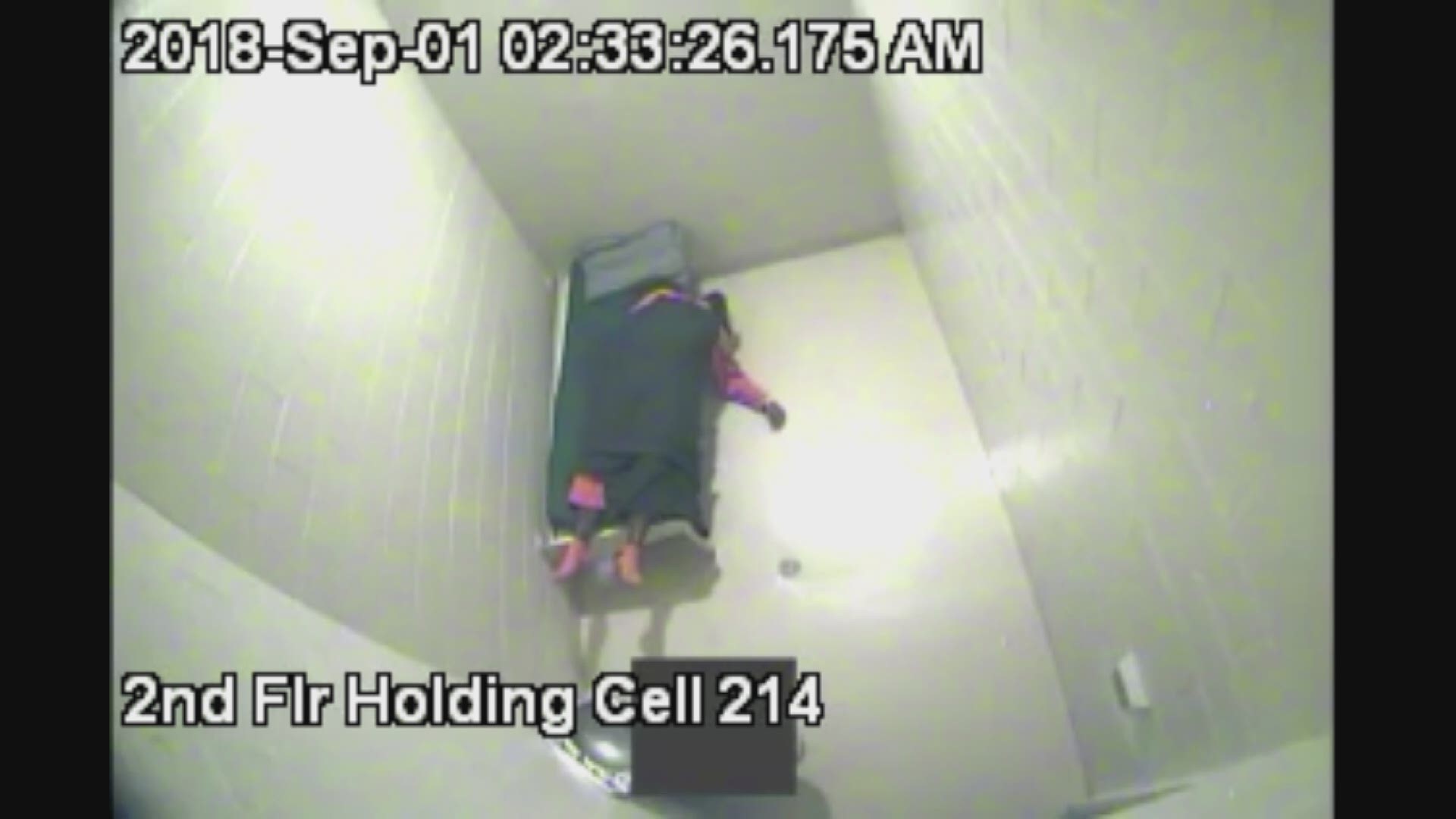

Late evening: Sherrell is placed in a medical segregation room, where he rolls off his bunk and falls onto the floor. He lays there for nearly eight hours.

Sept. 2

Morning: Sherrell asks for a shower after he urinates on himself. A guard tells him, “he can get up and shower at any time.” They ultimately help him shower.

3:29 p.m.: After two corrections officers change Sherrell’s diaper, one of them wrote: “I told Hardel that we are here to help but it would be nice if he would make an effort to help us out too.”

4:47 p.m.: A corrections officer goes to Sherrell’s cell and asks if he’s ready for something to eat, but Sherrell can only open and close his mouth as a response. Seeing that he could no longer speak, a guard calls for a nurse. As the nurse tries to take his vital statistics, Sherrell’s blood pressure drops. The nurse cannot find his pulse. A corrections officer begins using an automatic defibrillator on Sherrell.

5:23 p.m.: Efforts to revive Sherrell are stopped. He is pronounced dead.

Who is to blame?

The lawsuit filed by Sherrell’s mother names Beltrami County as well as MEnD Correctional Care.

In statements and court filings, both Beltrami County and MEnD have denied responsibility, directing blame for Sherrell’s death at another defendant in the lawsuit – Sanford Health, the hospital where he was evaluated two days before he died.

After an MRI at the hospital failed to find a problem, a Sanford physician diagnosed Sherrell with unexplained “Weakness/Fatigue” and sent him back to the jail.

In court filings, Sanford has also denied responsibility. A Sanford vice president said in a statement last week, "Due to privacy laws we are unable to comment on specific patients, but the safety of all patients and the quality of care they receive remain our highest priority.”

The whistleblower complaint filed just days after Sherrell’s death claims that despite his deteriorating condition, he wasn’t sent back to the hospital because MEnD’s Dr. Leonard “thought Hardel could wait until after the holiday to be reassessed.”

Multiple messages left for Dr. Leonard by KARE 11 were not returned. In court filings he has also denied responsibility.

A federal judge has ordered all parties in the case to be ready for trial by February 1, 2022.

Meanwhile, Sherrell’s mother vows to continue her fight for answers.

“He was crying out for help for days, not a couple of minutes – days! My son suffered for six long agonizing days,” Perry said. “Here’s a man that is dying right before your very eyes and you do absolutely nothing to help him.”

KARE 11’s investigative team has launched its own inquiry into medical care issues and deaths in Minnesota jails. If you have information to share with team, email us at: investigations@kare11.com