KARE 11 Investigates – The Gap: Failure to treat, failure to protect

Mass shooting in Buffalo reveals deadly gaps in Minnesota’s criminal and mental healthcare systems – as suspects declared incompetent in court fail to get treatment.

Gregory Ulrich walked through the doors at the Crossroads Clinic on a frigid February morning and first pointed his gun at a receptionist who asked if she could help him.

He set a briefcase carrying bombs on the ground, then according to court records and people there that day, he shot her in the stomach. He fired another shot at a nurse in the reception area, hitting her in the back.

He continued through a clinic hallway, unloading his 9mm Smith & Wesson handgun along the way. Two bullets hit the upper leg of a nursing assistant as she ran away.

Another six bullets went through a nurse’s chest, stomach, back, and left arm, leaving her in critical condition.

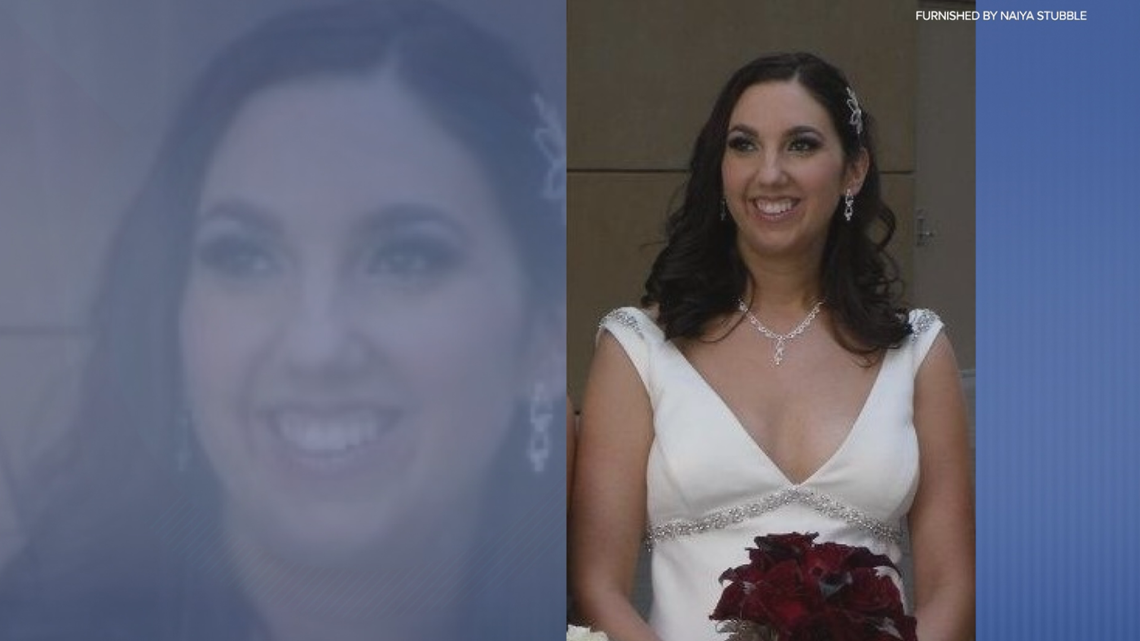

Of the 11 rounds he fired, only one hit 37-year-old nursing assistant Lindsay Overbay as she frantically ran for an exit. The bullet struck her stomach, passing through her liver and spine, before leaving through her back. Lindsay would die later that day.

She was a wife and mother of two young children.

As more became known about one of the worst mass shootings in Minnesota history, the more it became clear that it might have been prevented.

Ulrich is a “gap” case – where someone charged with a crime is found mentally incompetent to stand trial but fails to receive mental health treatment.

A KARE 11 investigation finds Ulrich is just one example of how gaps in the state’s criminal justice and mental health systems have failed to protect the victims in Buffalo – and in other communities statewide.

Chapter 1 Warnings Go Unheeded

Two years before he walked into the Allina clinic, Ulrich threatened to do exactly what he did, according to court records.

An Allina doctor told police Ulrich called him making threats “about shooting, blowing things up.”

A judge issued a harassment restraining order. Within weeks Ulrich was charged with violating it.

But he was found mentally ill and incompetent to stand trial, prompting the prosecutor to dismiss the case.

Despite the incompetency finding, no one ordered mental health treatment or supervision for him. Without those key protections, he was released back into the community – where he would go on to carry out his threats.

Ulrich is far from the only gap case in Minnesota.

A KARE 11 review of state court records found that since 2016, there have been more than 3,700 cases in Minnesota where defendants charged with a crime were found mentally incompetent to stand trial, but not court-ordered to get mental health treatment.

Studies have repeatedly shown that the vast majority of people struggling with mental illness are not violent and instead more likely to be victims of crimes or commit suicide. For those who are mentally ill and have a potential for violence, one study found that “Seemingly simple interventions can have a tremendous impact on violent outcomes.”

Too often, however, defendants found incompetent in Minnesota are turned loose without treatment – and with little more than the hope they won’t re-offend.

KARE 11 has identified cases in which defendants went on to commit arsons, domestic assaults, witness tampering, beatings, shootings and even murders.

Many of those cases began with incompetency findings for lesser crimes before people went on to commit something far more serious.

In one case, a St. Paul man who groped a woman outside an ice cream shop had his case dismissed after being found mentally incompetent. Released without court-ordered treatment, he was later accused of sexually assaulting two children in a parking lot.

A New Hope man was found incompetent in 13 different cases including domestic assault, disorderly conduct, and felony threats of violence. Two weeks after being found incompetent, he chased a woman down a hallway and held a knife to her 3-year-old’s throat demanding money.

When presented with KARE 11’s findings, State Sen. Jim Abeler, chair of the Human Services Reform Finance and Policy Committee, said he would call for legislative hearings – now scheduled for Sept. 15.

“It’s a mess. There are gaps here that simply should not be allowed to be,” said Abeler, a Republican from Anoka. “We are failing the humanity test. We are failing the protection to the public test.”

Abeler is not the only one calling for reform.

“Something needs to be done,” Lindsay Overbay’s husband, Donnie, said.

Chapter 2 From Normal to Frantic

The morning of Feb. 9 started as a normal day like any other for the Overbays.

Donnie remembers how he and Lindsay snuggled with their kids on the couch before Lindsay took their 8-year-old son to school and then went to work.

Donnie and their 5-year-old old daughter had started working on a puzzle when he got a text from a family friend.

“Do you know what’s going on?”

He hadn’t heard of anything. The friend sent him a breaking news story about the clinic. He was still holding the puzzle pieces when he rushed into his room to change out of his pajamas. He called Lindsay but got no response.

Donnie hurried his daughter to their truck and drove frantically toward the Buffalo clinic as text messages and phone calls started pouring in.

He pulled over into a parking lot, where a doctor told him that his wife had been shot and was being airlifted to a Minneapolis hospital.

Donnie tried to give nothing away as his daughter sat next to him. He wanted to show her that everything was OK.

He rushed to pick up their son, then get his kids to someone to watch them, all the while fielding questions he couldn’t answer.

“The hardest thing was having to lie to your kids,” he said.

He hurried to Minneapolis, but by the time he got there it was too late. Lindsay died on the operating table.

Chapter 3 'I Just Don't Understand'

As public attention turned to Ulrich’s history, Donnie learned about the prior threats the shooter had made against the Allina clinic and its staff.

Records show Ulrich was “angry with the medical community” and said he was “practicing different scenarios of how to get revenge."

When one of Ulrich’s doctors called Buffalo police in October 2018, he said his patient had threatened a mass shooting. “Ulrich stated he wanted it big and sensational so that it makes an impact,” according to the police report.

“I believe Ulrich is a high threat to society and himself,” Dr. John Burgdorf told police.

The doctor obtained a restraining order banning Ulrich from Allina facilities.

Despite the court order, records show Ulrich was arrested less than a month later at Allina’s Buffalo hospital. Criminal charges were filed accusing him of violating the restraining order.

In court, however, a judge doubted Ulrich’s ability to participate in his own defense and ordered a mental health evaluation to determine his competency to stand trial.

An evaluator reported back that Ulrich made statements “that appeared to be frankly delusional” and that he could not understand and participate in his case, citing his “grandiosity, paranoia and rigidity,” according to court records.

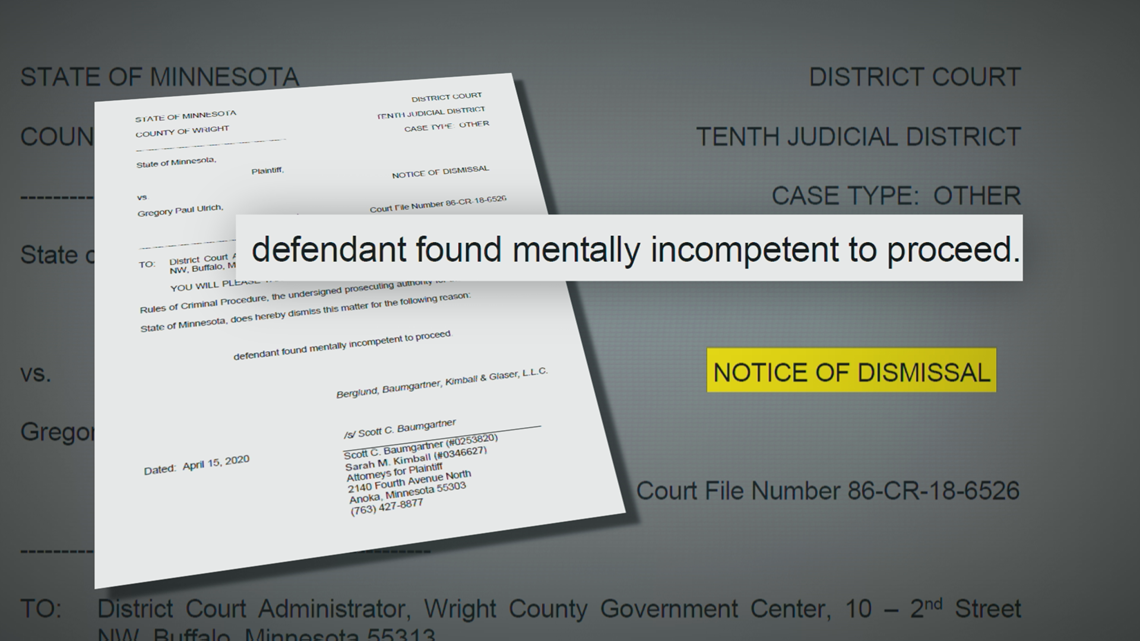

After getting the evaluation, Buffalo city prosecutor Scott Baumgartner dismissed the charge, an action that baffled Overbay when he learned about it.

“I just don’t understand why?” Overbay said.

What Overbay didn’t know: In Minnesota, court rules required Ulrich’s case to be dismissed.

Without the criminal conviction, he was able to buy a gun.

Chapter 4 Judges' Hands Tied

Minnesota’s system of handling mentally incompetent defendants is unique, according to a 2018 University of Minnesota study on gap cases.

A finding of incompetency in most other states typically triggers a requirement for defendants to at least get treatment to restore that person to competency.

Minnesota has no such requirement. One reason, according to the report, comes from good intentions: to not simply confine defendants for being incompetent to stand trial as many other states do.

“Minnesota’s current system holds the individual rights of mentally ill defendants in high regard,” according to the report.

But those good intentions have contributed to the gap problem.

If defendants are found incompetent to stand trial, Minnesota judges must order the county where the criminal case has been filed to hold a separate hearing to determine whether the defendant should be civilly committed – that is, be involuntarily provided mental health treatment.

A civil commitment requires more than a finding that someone is incompetent to participate in their own defense. Instead, people must be found to be a danger to themselves or others.

If defendants do not meet that criteria judges have little to no statutory authority to require treatment, KARE 11 has found.

Dakota County Judge Kathryn Messerich said Minnesota’s laws tie her colleagues’ hands.

“We don’t even have the toolbox, much less the tools,” she said.

Adding to that frustration, Messerich says under existing state court rules, if charges are misdemeanor offenses – like Ulrich’s restraint order violation – the charges must be dismissed, sometimes with tragic consequences.

“The cost is human lives,” she said.

Since 2016, there have been more than 1600 misdemeanor cases in which charges were dropped and defendants not committed for mental health treatment, according to data provided by the state courts.

What’s more, when cases are dropped by prosecutors – rather than by a judge’s order – it opens another gap.

As KARE 11 reported earlier this year, a judge’s ruling of mental illness could have been a red flag when Ulrich tried to buy a firearm. But records show no such ruling in his case.

As a result, Ulrich legally bought the gun he is accused of using in the Buffalo clinic shooting.

“I went to Fleet Farm and just bought it,” he told KARE 11 in a telephone interview from the Wright County jail.

Asked if any flags came up when he bought the handgun, Ulrich responded: “Of course not. I had no history.”

During the interview, Ulrich confirmed he never received mental health treatment after the criminal charges for violating the Allina doctor’s restraining order were dropped.

“I was mad, so I stayed mad,” he said.

On the day of the shooting, Ulrich called 911 to turn himself in, according to a transcript of the call.

When the 911 dispatcher asked him to “tell me anything that you can about the party that’s shooting,” Ulrich replied, “I am.” Moments later he added, “A bomb or two is gonna go off … I intend to surrender in a minute.”

Chapter 5 Gaps Across the State

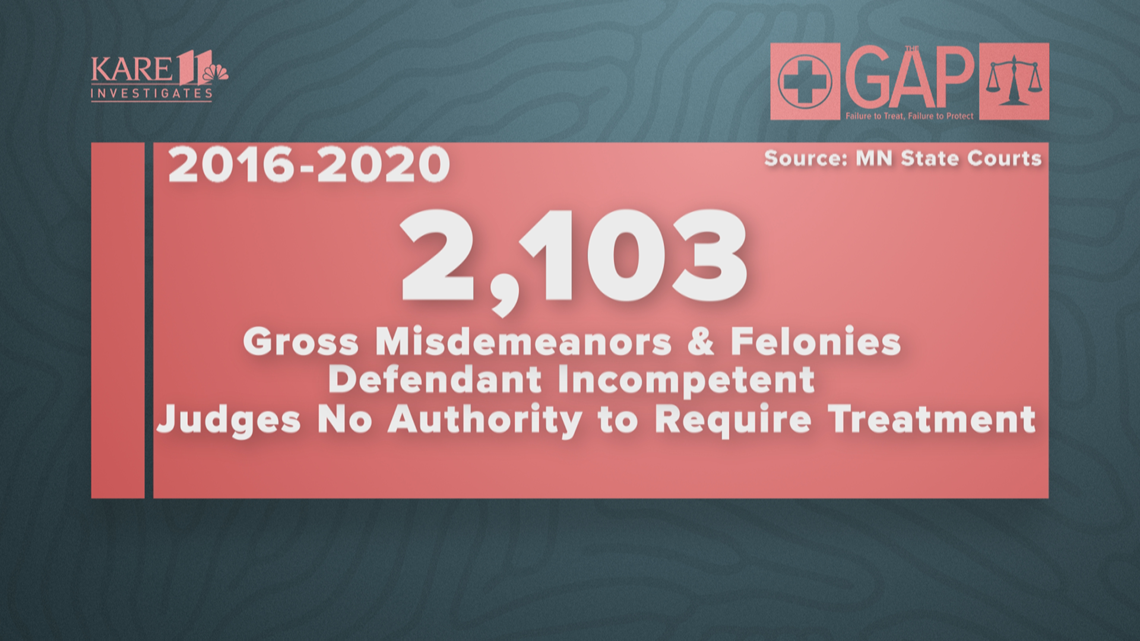

Minnesota’s gap cases don’t just involve misdemeanors.

Records reviewed by KARE 11 reveal they also involve more serious crimes – gross misdemeanors and felonies.

Since 2016 there have been more than 2,100 cases where defendants were charged with those crimes, found incompetent, but not committed, according to state court data.

Those cases have caused harm across the state, KARE 11 has found.

Joseph Vogel, for example, was charged with burglary three times in 2019 in Wright and Otter Tail Counties.

An Otter Tail County judge found Vogel incompetent to stand trial, but he was not committed for mental health treatment.

A year later while living in St. Cloud, he would be charged with slitting a dog’s throat and raping two women.

Only after he was found incompetent in those cases, did a judge order him civilly committed.

Chapter 6 Telling His Children the Truth

For Donnie Overbay and his children, there is a new normal. He is a single father, and they have no mother.

Soon after Lindsay died, he said he sat his children down, and with his family by his side, told them he’d lied to them – and that their mommy wasn’t coming home anymore.

After crying with them, he went out to his backyard, walked far away from the house where he thought no one could hear.

He broke down and screamed.