KARE 11 Investigates: VA disconnected phone leaves vets in limbo

Veterans searching for information about their benefits claims at the Department of Veterans Affairs are being routed to a disconnected number.

WASHINGTON D.C. - Veterans searching for information about their benefits claims at the Department of Veterans Affairs are being routed to a disconnected number, according to a new KARE 11 investigation.

An Air Force veteran from Minnesota says it happened to him earlier this month when a VA operator tried to transfer him to the Board of Veterans’ Appeals. He says it happened again when he dialed the same number directly.

KARE 11 dialed the same number and confirmed it’s been disconnected.

Veteran Offered Veterinary Service

From the kitchen table of his Avon, Minnesota apartment, Bob Morris dials a Washington D.C. phone number that is supposed to be an official Department of Veterans Affairs line.

With a thinly veiled look of disgust on his face, he places the phone on speaker, knowing what is about to happen.

A couple of rings, and then an automated voice answers, “The number you called is not in service.”

Morris rolls his eyes as the voice continues, offering to connect the caller with businesses including locksmiths, and plumbers.

“That’s the answer they give you,” said Morris. “Call a plumber or some damn thing!”

To add insult to injury, the recording goes on to suggest a veterinary service.

Morris is not calling for his dog. He is trying to reach the Board of Veterans’ Appeals to schedule a hearing.

He is one of nearly 470,000 veterans who as of March 1, 2017, are caught in the bureaucratic limbo of the VA’s benefits appeals process.

Agent Orange Denials

“Here is my medication drawer,” said Morris opening his bathroom cabinet to reveal rows of pill bottles.

“I don’t have to eat breakfast after taking all those pills,” he joked.

Morris believes his cancer, heart disease, and other illnesses including high blood pressure and diabetes are likely rooted in his time in uniform.

He recalled his meeting with the VA doctor in St. Cloud who diagnosed his cancer. “The doctor that found it, the first thing he said to me was were you ever exposed to Agent Orange?”

The answer to that question is where Morris and the VA are at an impasse.

Agent Orange, the toxic herbicide the U.S. military used to remove jungle foliage in Vietnam, was also used in Korea along the de facto border between the North and South known as the demilitarized zone or DMZ.

The treated strip of land was 151 miles long and up to 350 yards wide.

The VA’s website states veterans who served in Korea in or near the DMZ between April 1, 1968, and August 31, 1971, and have a disease VA recognizes as associated with Agent Orange exposure are presumed to have been exposed to herbicides.

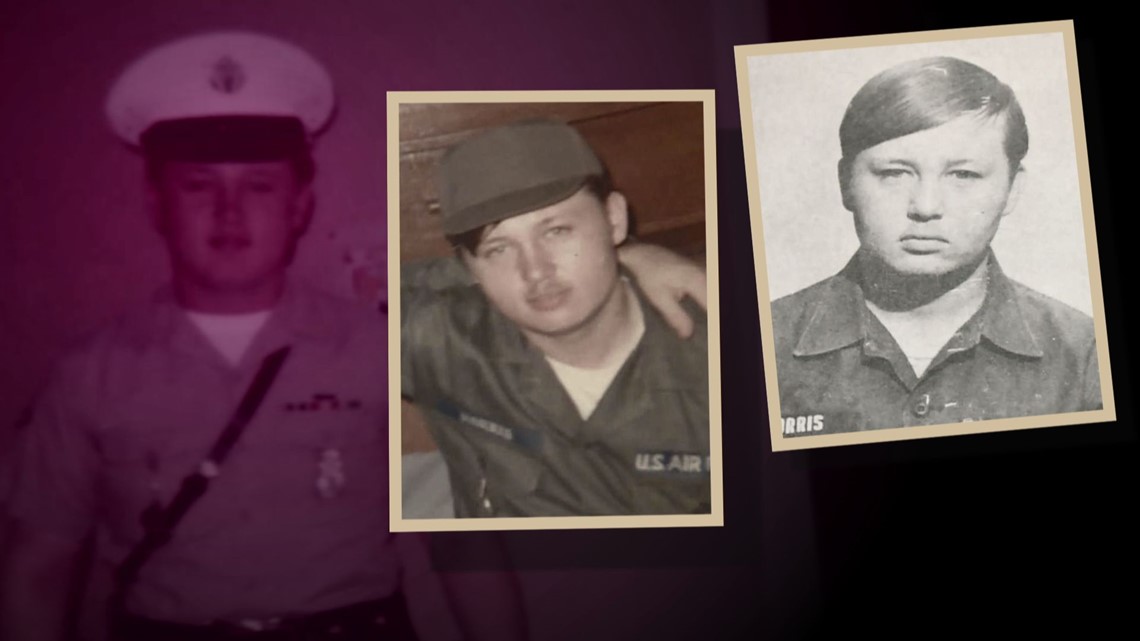

Morris served in Korea in 1970 and 1971 with the Airforce 6175th Security Police Squadron.

However, the VA has repeatedly denied the disability compensation claims he has been filing since 2005.

“Nothing but denials, denials,” Morris exclaimed!

The VA’s argument is there’s no proof Morris was at the DMZ.

His main duty station was KUN SAN Air Force Base, located on the shores of the Yellow Sea on South Korea’s west coast. That’s about 109 miles south of the DMZ.

But Morris contends he spent several weeks at the DMZ for training.

“If you were in the 6175th police squadron, it was mandatory that you went to the DMZ for your combat and weapons training,” he said.

“We were basically digging into the dirt where the agent orange was being sprayed,” he added.

Morris says the government lost his military records in a fire, but he contends he has proof he was at the DMZ.

In addition to letters from fellow service members that confirm he was at the DMZ for training, Morris has a cassette recording he mailed from Korea to his parents in St. Cloud, MN.

He showed KARE 11 the original Air Mail postage and Customs Declaration that states “cassette tape.”

In the recording, which is basically a voice letter to his family, he describes being at combat preparedness school and firing all sorts of weapons “up at the DMZ.”

With the resolve of a man who knows he is right, Morris refuses to take the VA’s benefits denials and go away quietly. “I never would have asked for it, but they tell you - you got it coming,” he said.

But Morris claims he’s getting the run-around from the VA.

“It’s very frustrating!” he said. “You do everything they tell you to do, and then when it comes time for something to come down, they let you hang.”

He says the latest example is the VA’s disconnected phone line.

Left on the Line

Appealing a denial from a 2014 benefits claim, Morris requested a live video hearing with the VA’s Board of Veterans’ Appeals.

“I heard it would be faster if I could get a video conference,” Morris recalls.

The Department of Veterans Affairs touts the video hearings between veterans and Veterans Law Judges in Washington D.C. as having increased convenience, and shorter wait times.

RELATED: More on BVA Video Hearings

On January 18, 2016, Morris received a letter from the Regional Benefits Director in St. Paul stating that his records were being transferred to the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA) in Washington.

The letter also stated, “BVA will notify you when they have received your records.”

A year passed and Morris says that notification never came.

“I think they’re using pony express because I still haven’t gotten my conference,” Morris said with resigned laugh.

He said he called the Department of Veterans Affairs in January, 2017 and was told he’d receive a letter by early March.

When that letter did not arrive as promised, he called the Department of Veterans Affairs again. This time he recorded the phone call.

The woman who answered was courteous, but could find no record that a letter was supposed to be mailed.

“The Board of Veterans’ Appeals are the ones that would set that up for you,” she tells Morris during the call.

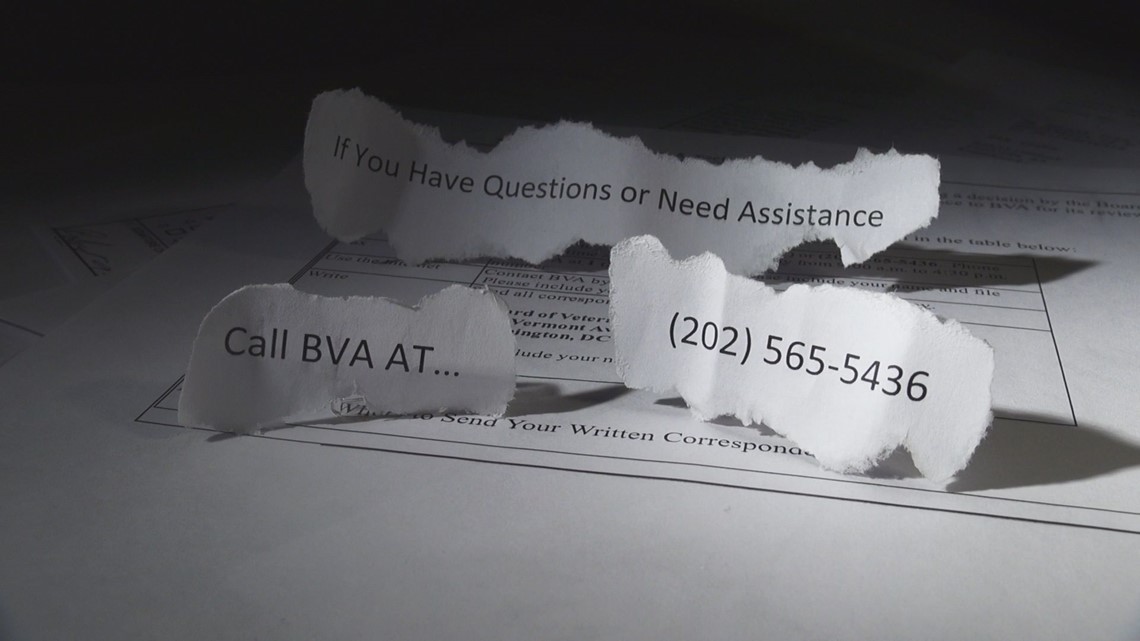

The VA employee gives him two numbers he could use to reach the BVA. One was 1-800-923-8387. The other was 202-565-5436.

The recording shows she then politely offers to transfer Morris to the 202 number.

“Thank you for your service to our country,” she says. “I’m going to transfer you to the 202 number. That’s 202-565-5436. That’s the Board of Veterans’ Appeals. One moment please.”

The phone rings a few times then goes to an automated message saying the number is no longer in service.

Instead of directing Morris to a new VA number, the automated directory assistance recording suggests connecting to private businesses including locksmiths, plumbers and a veterinary service.

“I needed to find out where I was in line with my video conference on my appeal, I got a locksmith instead,” Morris said as he smacked his hand in frustration on his kitchen table.

At first, Morris thought it might have been a misdial by the VA employee who transferred him.

“I couldn’t believe it you know, I thought well they gave me the wrong number,” he remembers thinking. “So I redialed the number she read off to me and I got the recording again.”

Next, Morris says he tried calling the other number he’d been given, the 1-800 line. But that didn’t work either.

“The phone’s ringing and the phone’s ringing,” he recalls.

Morris says it just rang dozens of times, then disconnected with no opportunity to even leave a message.

Calling KARE 11

The veteran’s next call was to the KARE 11 investigative team. KARE tried calling the same numbers Morris was told he had to use to get answers about his Agent Orange benefits claim.

The results were the same.

One line is disconnected and routes the caller to locksmiths and veterinarians. Meanwhile, the 1-800 line rang for more than three-minutes, then disconnected.

Both numbers given to Morris are listed on the Board of Veterans Appeals official web page and instruction documents.

It wasn’t just a one day problem.

KARE Investigative Reporter A.J. Lagoe sat with Morris one week after the veteran’s first failed call to the VA and watched as he tried again.

For Morris, it was a case of bureaucratic déjà vu. The first line remained disconnected and the second went unanswered.

“Well there I got my help again,” he said, slapping the table with one hand while hanging up his phone with the other.

“I’m getting used to it, it’s the way they treat us.”

“I am sure I am not the only veteran out there with these problems,” he said.

He’s right.

On June 23, 2016, then-Deputy Secretary Gibson testified before the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs that the VA estimates that on average, it can take three years to resolve an appeal at the Regional Office level and five years to process an appeal that goes to Board of Veterans’ Appeals.

KARE 11 contacted the Department of Veterans Affairs early Monday to report the problem. By the time government offices closed Monday evening, the VA had not responded - and the 202 number listed on government forms was still not in service.