CASS LAKE, Minn. — It was a phone call Frank Sherman has been waiting six years to get.

“They called and told me I’m on the organ transplant list!” Frank exclaimed.

It’s a victory in a six-year battle for the Marine Corps veteran from northern Minnesota who needs a new kidney.

The decision by the Department of Veterans Affairs came after a KARE 11 investigation raised questions about whether Sherman had been unfairly denied a chance for a transplant.

Years of denials

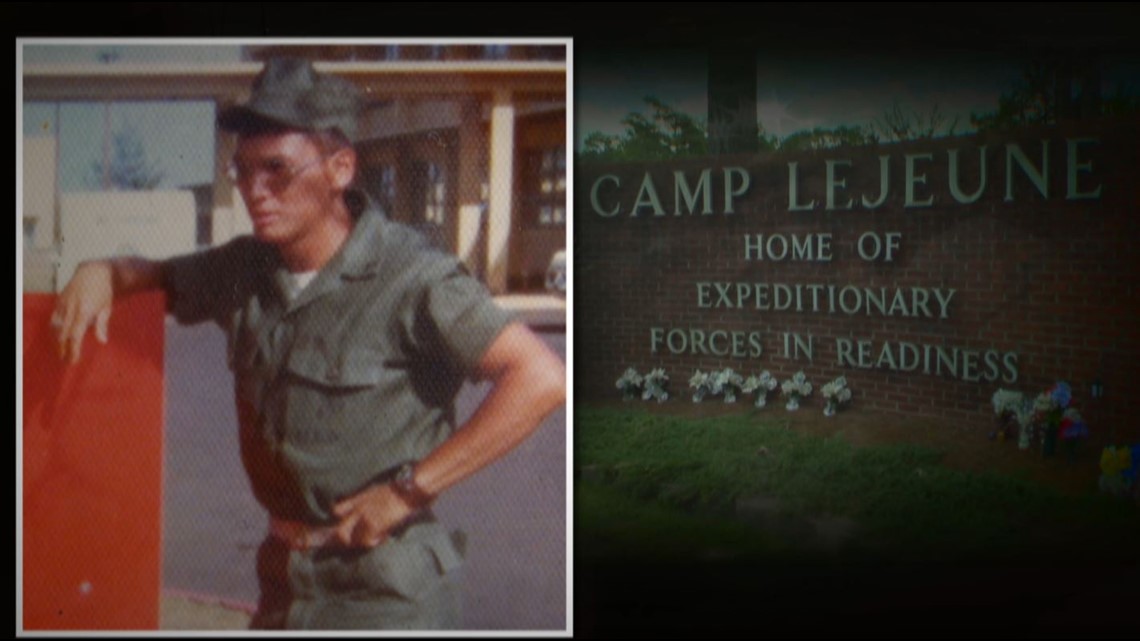

A member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, Frank served in the Marine Corps from 1972 to 1976, rising to the rank of sergeant.

He now has end stage renal disease. His VA records show it was likely caused by drinking contaminated water during his service at Camp Lejeune.

In June 2018, KARE 11 investigated why the VA had refused to put the veteran on the transplant list despite recommendations from all of his doctors. They called him a good candidate for a transplant.

“There is no valid reason for him not to be selected,” Dr. Mark Becker, Frank’s primary care physician at Cass Lake Hospital, wrote to the VA.

Frank’s private nephrologist concurred. “I think that Frank would make a good transplant candidate,” Dr. Jason Bydash told KARE 11.

VA records show the Minneapolis VA’s Chief of Nephrology even referred to Frank in 2015 as an “average risk candidate for kidney transplant.”

Still the VA denied him.

Records reviewed by KARE 11 indicated Frank was denied because the VA believed he was not mentally alert enough to follow medical instructions and take care of himself after a transplant.

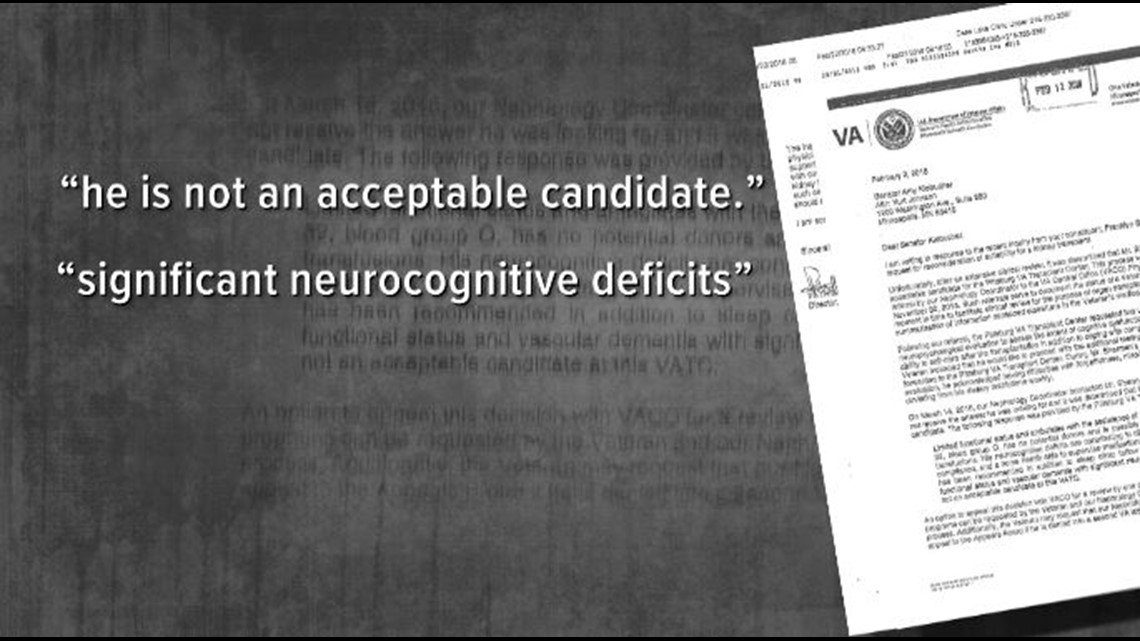

When Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) asked about Frank’s case in February, Minneapolis VA Director Patrick Kelly cited a finding by the Pittsburgh VA Transplant Center: “Due to his limited functional status and vascular dementia with significant neurocognitive deficits, he is not an acceptable candidate.”

Dr. Bydash told KARE 11 he believed the VA made a life-threatening mistake. “Frank, in my opinion, does not have significant neurocognitive deficits,” he said.

Frank’s primary care physician at Cass Lake Hospital agreed. About the VA’s claim Frank had cognitive impairments, he wrote: “This is simply not true.”

Questionable test results

Frank grew up on the reservation speaking Ojibwe and does not read well. So, records show he did poorly on a standard memory test used to determine whether he could care for himself after the transplant.

But records reviewed by KARE 11 raised serious questions about the accuracy and fairness of the VA’s interpretation of the results.

Frank says he was asked to recall lists of words and names. But he says the test included words he didn’t know.

In fact, KARE 11 discovered one of the VA’s own examiners had noted in a report that Frank “appeared unfamiliar with a number of items.” Citing the word escalator as an example, the examiner reported Frank said, “We don’t have those on the reservation.”

“And they think because you don’t know a word that’s a memory. It’s not a memory, it’s a word you don’t know.” Frank said.

A note in Frank’s records stated, “Patient performance was scored on Caucasian norms due to lack of Native American norms available.”

Others notes by VA examiners stated that “cross-cultural factors … may have contributed to suppressed performance.” The examiner concluded, “Results of the current evaluation may therefore potentially underestimate his true level of cognitive functioning.”

Even so, the VA refused to put Frank on the transplant wait list.

“What does that say to you?” KARE 11 investigative reporter A.J. Lagoe asked Dr. Bydash.

“It says it’s a biased system,” Bydash responded. “Testing may pick up on certain defects erroneously - especially if it’s using language that they’re not familiar with.”

A pattern of problems

Frank’s case is part of a broader problem.

KARE 11’s two-year “Distance, Delays and Denial” investigation exposed deadly delays, prohibitive travel requirements, and inconsistent, overly restrictive eligibility criteria in the VA organ transplant program.

“How many patients do you think unnecessarily died?” VA whistleblower Jamie McBride was asked.

“Thousands,” he replied. McBride is the Manager of Solid Organ Transplants at the VA hospital in San Antonio, Texas.

In early 2018, the head of a government watchdog agency accused the Department of Veterans Affairs of failing to properly address McBride’s complaints about systemic flaws that limit access to life-saving organ transplants for veterans nationwide.

In his letter to the President, Special Counsel Henry J. Kerner wrote, "Mr. McBride deserves praise for bringing forward the numerous barriers to life-saving organ transplants for veterans."

Research by experts at the Cleveland Clinic and the University of Pennsylvania backed up much of what McBride disclosed. Veterans who rely on the VA for kidney transplants are less likely to actually receive a transplant - and more likely to die waiting - compared with other patients in need of the same surgery, according to findings released in November 2017 by Dr. Joshua Augustine of the Cleveland Clinic.

The reporting sparked Congress to write new legislation, and President Trump in June 2018 signed reform measures into law as part of the VA Mission Act.

The new law allows veterans to get transplants closer to home and gives more control over whether they need a transplant to their primary care doctor. However, veteran’s advocates report they’re still experiencing problems getting VA management to sign contracts with local hospitals.

New testing and new hope

After KARE 11’s report about Frank’s testing aired, the VA gave him a new evaluation. That testing suggested “largely stable cognitive and functional status.”

This time the VA examiner wrote, “current exam results do not support a diagnosis of Major Neurocognitive Disorder.”

Frank says he and his family knew all along there was nothing wrong with his memory. “But nobody seemed to want to listen to that,” he said.

The VA reconsidered its previous denial and has now reversed course. Frank says the decision to put him on the organ transplant list has given him new hope.

“I could hardly believe it,” Frank said after getting the good news.

Being on the official transplant list, however, is not a guarantee Frank will get a kidney in time to save his life. Time is not on his side. The average life span of a patient on dialysis is just five years. Frank has been on dialysis since 2012.

“Now, at least they’re giving me a fair fighting chance,” he said.

If you have a suggestion for an investigation, or want to blow the whistle on fraud or government waste, email us at: investigations@kare11.com