KARE 11 Investigates: How one state changed its practices and ended juvenile solitary

If Minnesota is looking for solutions on ending juvenile solitary confinement, it might look to Colorado, which ended the practice and made the state safer.

Noah couldn’t take it anymore.

Almost a year into being at the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center last October, a guard told the teenager he was going to write him up for punching all the buttons in an elevator, according to facility records.

That set Noah off. He started throwing food, the kind of violation that gets JDC kids thrown into solitary.

Solitary can be a few hours, maybe days, maybe weeks, Noah said in an interview with KARE 11 from inside the JDC.

He said he feels dirty in solitary. He doesn’t feel human. He feels like an animal.

“It’s something you can’t fight.”

Noah tied one end of a sheet to a door handle, then wrapped the other end around his neck.

Had a guard not checked on Noah during their rounds, he might be dead. He’s tried to kill himself at least twice more since then.

Minnesota’s juvenile lockups routinely put kids like Noah into solitary confinement, as KARE 11 has previously exposed. The practice – known as “Disciplinary Room Time” – has no restrictions on how often it can be used, nor how long kids can be placed into solitary.

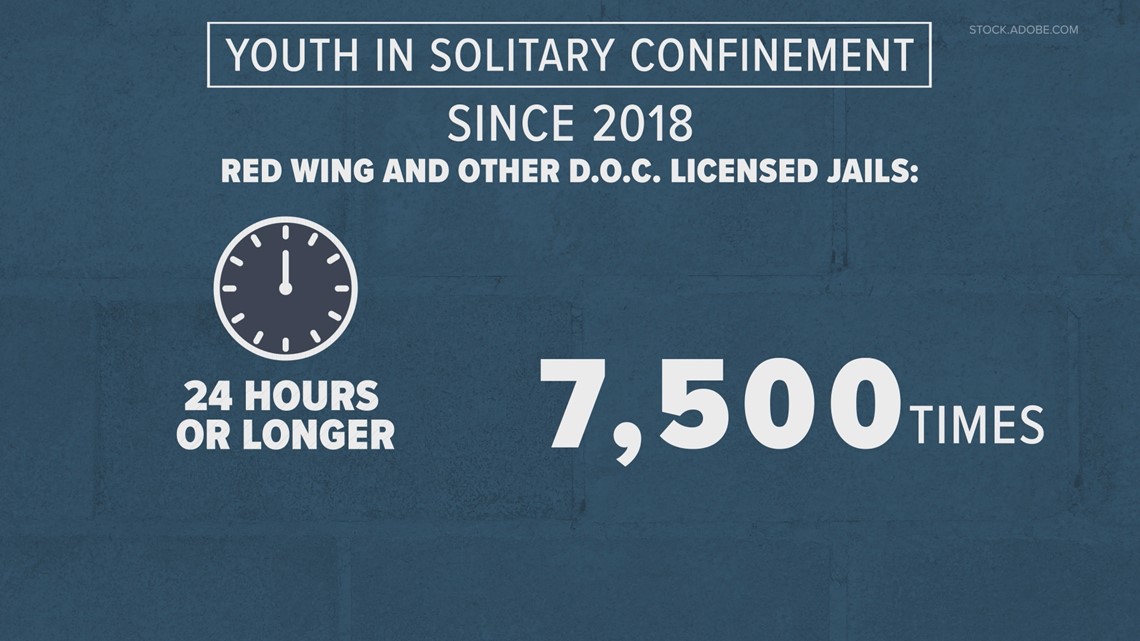

Records reviewed by KARE show that juvenile detention facilities and the state’s juvenile prison have ordered kids into solitary for 24-hours-or-longer more than 7,500 times in the last five years.

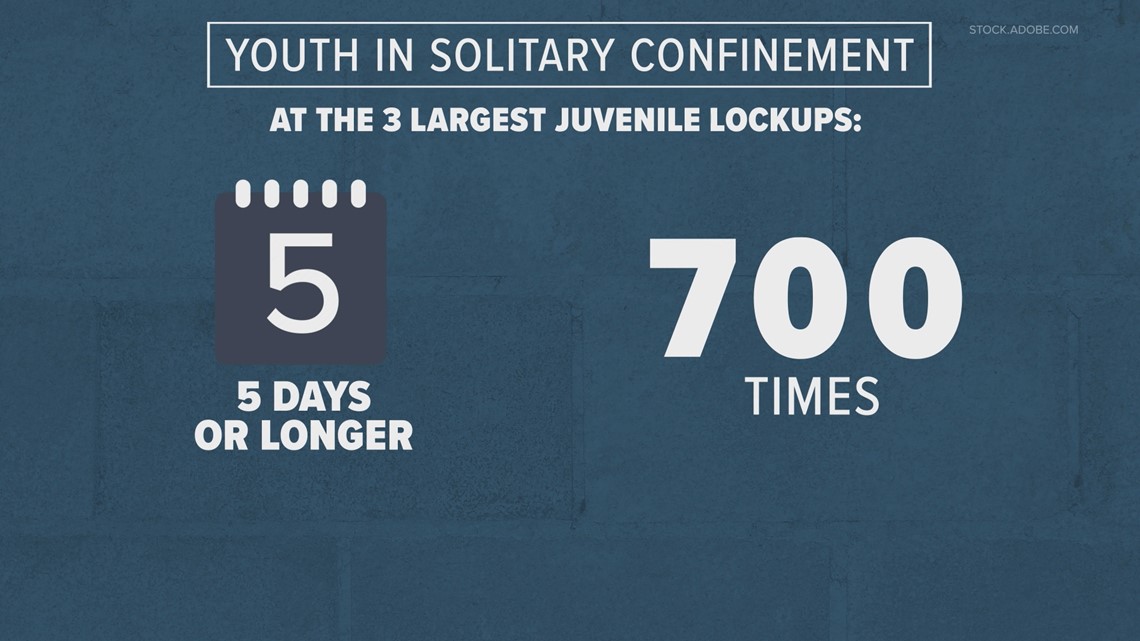

Minnesota’s three largest juvenile lockups have ordered kids into solitary for five days-or-longer nearly 700 times since 2018.

The mental health impacts can be devastating. One study found that half of the kids who committed suicide in juvenile detentions did so while in isolation.

It’s a practice that numerous experts say can also make children even more aggressive, putting the public at risk when they’re released.

“You’re not supposed to put kids in their own time-outs for five days,” said State Sen. Ron Latz, the chair of the Senate Judiciary and Public Safety committee. “It would probably qualify as child abuse under Minnesota law if you did that.”

'Their behaviors change'

One state to turn to for answers may be Colorado, which until about seven years ago placed about the same number kids into solitary as Minnesota does today.

Despite that, fights and assaults increased at Colorado’s juvenile lockups, even as the number of kids in detention facilities decreased, according to a report by a state child safety coalition.

“It’s probably no surprise, (solitary) didn’t reduce their aggression,” said Anders Jacobson, who was appointed director of the Colorado Division of Youth Services (DYS) in 2016 to begin reforming the state’s juvenile detention facilities.

Jacobson had been the director of one of Colorado’s juvenile lockups, where he saw firsthand the impact of putting kids into solitary.

“You would see their behaviors change. Their psyche change,” he said. “They don’t get well sitting in a locked room.”

The legislature changed the state’s law in 2016 to allow seclusion only when there was an imminent threat of bodily harm. A court order is needed to hold a kid in seclusion for more than eight hours in two days.

Fast forward to today, where Colorado has cut the number of times kids are put into seclusion to an average of eight a month in 2022, according to the state’s records.

The average amount of time kids spend in seclusion is about half an hour.

The average time spent in solitary at the Hennepin JDC is about 48 hours. At the Red Wing juvenile prison, the average time is 58 hours.

The public saw a benefit to Colorado’s solitary ban. The number of youths who re-offended within a year has been cut almost in half to the lowest level in nearly a decade, according to the state’s data.

Success, but at a cost

Such a drastic drop in seclusion and recidivism in Colorado wasn’t easy, requiring a culture change in how youth were treated in juvenile facilities.

And that wasn’t cheap.

The state spent an extra $9 million to hire nearly 200 more employees to reduce its staff-to-youth ratio. What had been about one staff person to every 20 kids has gone down to one-to-five, according to the state.

Jacobson said that’s allowed more direct intervention and counseling with children who act out.

If a kid assaults someone, for example, Jacobson said a staff member separates the youth from the rest of the population. But instead of going into isolation, staff would work directly with the child, talk about appropriate behaviors, what can be learned from the incident, and how to safely return to being with other kids.

Seclusion could be an option if the child doesn’t calm down – and even then, only for a short period of time.

A philosophy of punishment was replaced with one that emphasized de-escalation, treatment, teaching, and rehabilitation. The state also banned use of full body restraints and pain compliance holds, practices still allowed in Minnesota’s juvenile lockups.

The state also remade its detention facilities into what Jacobson called “a homelike environment.”

Or as Jacobson put it: “How do you suck out as much of the correctional feel in the environment as possible?”

Gone were detention centers that looked like jails, replaced with brighter, more welcoming common areas where fewer kids lived and interacted, and rooms that looked more like bedrooms rather than cells.

When kids feel supported, Jacobson said, “that’s going to limit behavior significantly.”

But there have been growing pains. When Colorado started shifting toward its rehabilitative model, Jacobson said 15 to 20 percent of existing employees left, fearing kids would take over the facilities and assaults would skyrocket.

“Thankfully to date that did not play out,” Jacobson said.

Two years after the reforms, the state saw about a 2 percent increase in the rate of assaults on staff and other youth, which the state’s DYS attributes to a significant spike in the number of kids coming to the facilities charged with violent crimes.

Last year, however, the number of assaults dropped to its lowest levels in nearly a decade.

Life inside the JDC

The day he was brought to the Hennepin County JDC in November 2021, then 17-year-old Noah had run away from home again. He’s mentally ill and autistic, according to court records, and grew up physically and emotionally abused by his stepfather. As he grew older, he started skipping school and abusing drugs. His behaviors got worse. He stole cars and gave others Xanax laced with fentanyl.

He called his mom, Noelle, that day in November and told her he hurt someone. She called the police, who at the same time were looking for the man who repeatedly stabbed a man in the back at a South Minneapolis laundromat. Noelle helped the police find him.

Charged with first-degree assault, Noah, now 18-years-old, has been in the JDC for 461 days, as attorneys battle over whether to try him as an adult and whether he acted in self-defense, as he claims.

Noelle never expected life in the JDC to be an easy one for Noah.

“I don’t expect it to be, and I’m not asking for it to be,” she said. “But I don’t think it needs to be this dark, and this hopeless either.”

What he describes in interviews with KARE 11 is a facility where sunlight is rare, violence is constant, and solitary is common. Many of his assertions are also supported by records and other interviews.

He said he’s been outside about eight times the entire year. He’s gotten into fights, and once was beaten so badly he was taken to the hospital for a cracked skull.

He’s been put into solitary repeatedly, where he feels like he’s in a cage.

“There’s a light on 24/7. They don’t ever turn it off. It does something,” he said. “Nobody’s opening your door. You don’t get anything that could give you joy or enjoyment at all.”

Despite attempting suicide at least three times, he said he’s gotten little mental health care.

He has no idea when he’ll get out.

Asked what he thinks could make life inside the JDC better, what he describes is similar to what already happens in Colorado:

“It should be a priority to help heal the people that are broken, instead of treating us like animals,” he said. “The way we’re treated, it brings them to violence, stress and depression, and just makes everyone hopeless.”

If you or someone you know is facing a mental health crisis, there is help available from the following resources:

- Crisis Text Line – text “MN” to 741741 (standard data and text rates apply)

- Crisis Phone Number in your Minnesota county

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), Talk to Someone Now

- Throughout Minnesota call **CRISIS (**274747)

- The Trevor Project at 866-488-7386

Watch more KARE 11 Investigates:

Watch all of the latest stories from our award-winning investigative team in our special YouTube playlist: