Some moaned. Others moved very little. At least 20 said, “I can’t breathe.” Most were mentally ill. Many were obese. More than half had drugs in their systems. More than two-thirds were either Black or Hispanic.

Some names, like George Floyd or Eric Garner, you likely know well.

Others, like David Baker or Roy Nelson, you might not have heard mentioned at all.

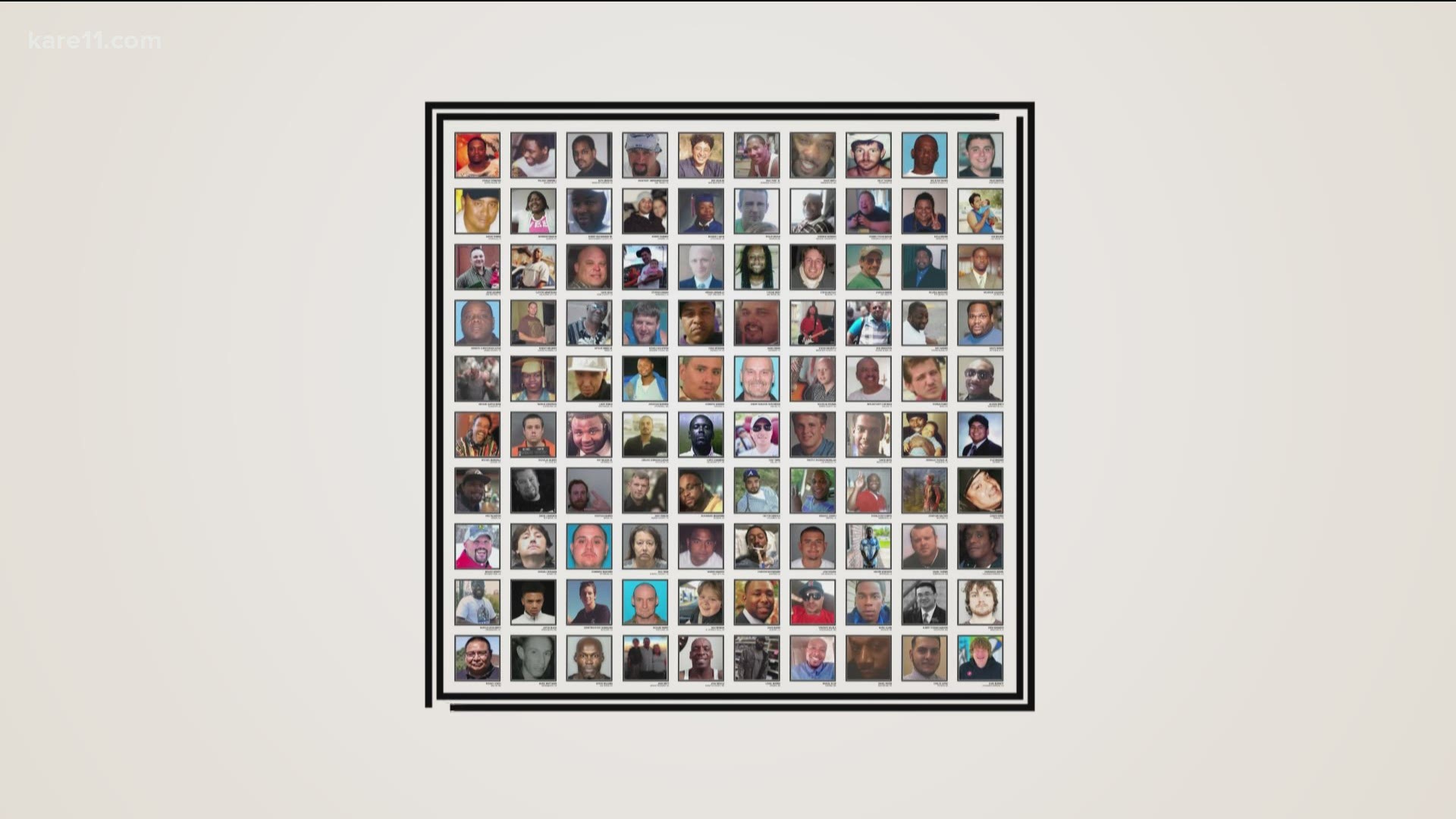

In all, this investigation found at least 107 names of people nationwide who died facedown and on the ground since 2010. There are likely many more.

All were, at one point, held prone. In other words, they were restrained on their stomachs while officers tried to handcuff them.

By our count, their deaths have led to more than $70 million in settlements and verdicts.

INTERACTIVE GRAPHIC: Click the photos for the names of people who 9News found died of positional asphyxia and more information about each case.

Yet not even that figure has proven enough to convince law enforcement officers to do what they were advised to do back in 1995 when the U.S. Department of Justice through its National Institute of Justice Program told officers: “As soon as the suspect is handcuffed, get him off his stomach.”

Why issue the warning in the first place?

“In a recent analysis of in-custody deaths, we discovered evidence that unexplained in-custody deaths are caused more often than is generally known by a little-known phenomenon called positional asphyxia… a person lying on his stomach has trouble breathing when pressure is applied to his back,” the report reads.

The chances of someone dying after being held prone are not great, but they aren’t non-existent either. And what do officers risk by getting someone off his or her stomach once that someone was handcuffed?

“There’s really no downside to it, only upside,” said Jack Ryan, a national law enforcement trainer and former police officer. “I say this all the time during training: ‘What do you have to lose by doing it?’”

Before COVID-19, Ryan spent nearly 40 weeks of the year training officers across the country.

“I’ve said in training that we ought to have it printed on the tip of the dashboard of the police car or maybe tattooed on the backs of peoples’ hands: ‘Get off of them, and get them into a position that facilitates breathing,’” he said from his home in Rhode Island. “This is important stuff.”

Yet we now have at least 107 reasons to believe the message hasn’t exactly taken hold.

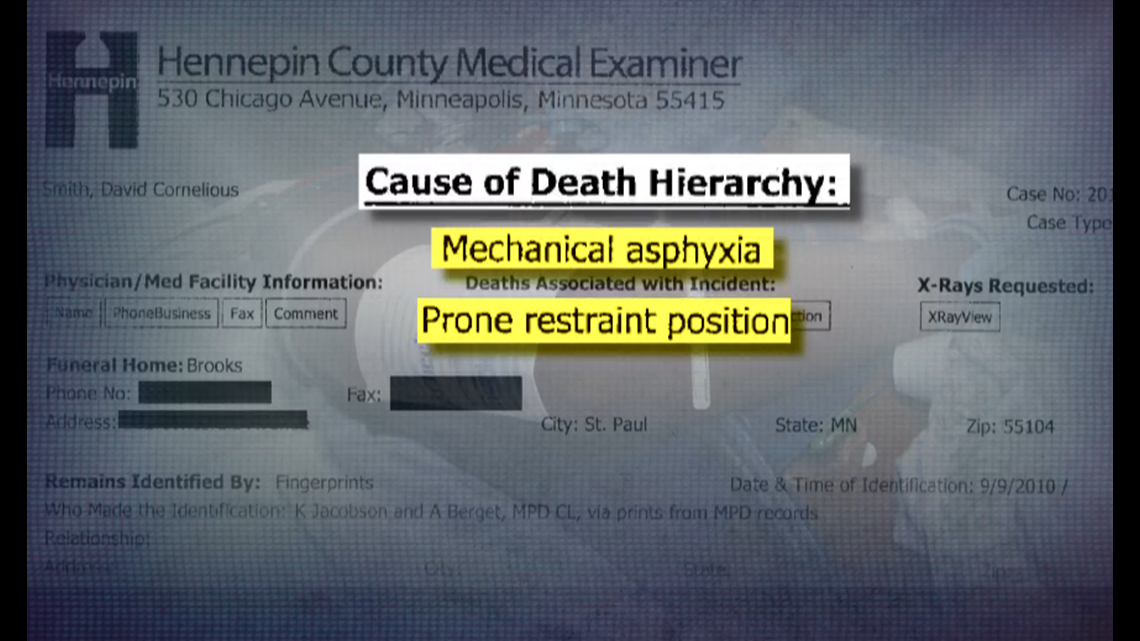

David Smith was a 28-year-old Minneapolis man who loved poetry and acting. He was diagnosed as bi-polar in college, but his family says he didn’t let it define him and was living a happy, productive life.

"He was amazing, and he meant so much to us," said his sister Angela Smith.

David committed no crime, but his behavior at the downtown Minneapolis YMCA in 2010 raised red flags for staff and the police were called.

The incident escalated into a struggle. Video shows it ended with officers kneeling on David Smith’s back for about four minutes.

An officer can be heard saying, "I don't think he's breathing."

Smith’s autopsy shows he died due to “mechanical asphyxia” caused by prone restraint.

Smith’s family sued. It ended in one of the largest lawsuit payouts for police misconduct in Minneapolis’ history.

But his family says they wanted something far more important than money.

“When David was killed, we wanted to make sure this never happened to anybody else,” his sister said.

The family insisted the lawsuit settlement agreement include language that the city would “require its sworn police officers to undergo training on positional asphyxia...”

After watching George Floyd die, the Smith family questioned whether that promised training was taken seriously by MPD.

David Baker’s death outside his estranged wife’s apartment in Aurora, Colorado in late 2018 received little attention outside of the state.

Body camera footage revealed Baker was the aggressor, at least at first.

It took seven officers to hold Baker, a Navy veteran struggling with mental health issues, on the ground.

Yet once they handcuffed him, Baker’s aggressiveness waned. Minutes later, facedown, the 32-year old father stopped breathing.

A medical examiner would later conclude Baker died of “restraint asphyxia” and called the death a homicide. A few months later, prosecutors decided it was a justified homicide based on Baker’s actions.

Baker’s death, taken merely on its own, might not signify much.

There has been no lawsuit. No officers were ever disciplined for their roles in his death.

But, his death is hardly the only one to happen in such a way.

The day before the high-profile death of George Floyd this year, five police officers in Colorado Springs, Colorado, held a handcuffed Chad Burnett facedown for more than six minutes inside his home in the city’s upscale Broadmoor neighborhood. Police had responded to the home after a caller reported Burnett had shown a knife during an argument just outside.

Body camera footage reviewed by 9News show Burnett stopped moving roughly halfway through those six minutes.

“Chad, you doin’ alright?” asked one of the officers.

“We’re sorry this happened, but you have to listen to the police, ok?” said another.

By the time officers rolled Burnett over, Burnett had clearly stopped breathing.

“Hey Chad! Chad! Wake up, pal!” said an officer.

The coroner said Burnett died due to “underlying heart disease” and from being tased. Prosecutors decided not to file any charges, saying the officers used “reasonable force.”

One of Chad’s closest friends said that Burnett had been dealing with some mental health issues.

“I think him having to deal with the isolation of COVID just sort of sent him into a dark place,” said Brett Lindstrom. “He was having this psychological break, and he probably felt like everybody was out to get him at that point.”

During this investigation, our reporting team built a database of deaths of people who suddenly died after being held in a prone position.

Using autopsy reports and court filings, we examined each of the deaths looking for commonalities.

While 53% of the people who died had drugs in their systems at the times of their deaths, the number one commonality was not drug use but mental illness. Mental illness was cited 60% of the time.

Obesity was also a common characteristic.

Only five cases involved people who didn’t share at least one of the following characteristics: obesity, drug use, mental illness or the use of a taser.

Tami and Walter Turner watched their 41-year-old son die right in front of them two houses down from their own Farmington, New Mexico home, on June 28, 2018.

“Daniel was easy-going, to a fault probably,” Tami Turner said.

That night, Walter Turner called 911 after he saw his shirtless son banging his head on the road next to their home.

“He’s out running around. I think he’s on something,” said Walter Turner on the 911 recording.

“We had a medical emergency, and that’s what we called for,” Tami said. “We’re still thinking at that time that someone is coming to help us.”

Shortly after Farmington Police officers arrived, Daniel Turner was on the ground, facedown and handcuffed.

Body camera footage reviewed by 9Wants to Know show officers continuously trying to talk to Daniel.

“Hey man. Did you take something? What’s going on?” said one officer.

Seconds later, that officer said, “His breathing is slowing down big time.”

In all, Daniel Turner was held prone and handcuffed for more than three minutes.

“Daniel! Daniel!” shouted an officer shortly before Daniel was turned over.

“CPR in progress,” said a dispatcher over the police radio.

Daniel died within eyesight of his parents’ home.

“Me and Walter do not ever drive down that street anymore,” Tami said.

“We’ve never driven down that street since it happened. We won’t go that way,” Walter said.

Tami and Walter Turner have filed a lawsuit in federal court alleging, among other things, that Farmington Police officers’ tactics that night directly contributed to their son’s death.

Farmington Police issued a statement which read, in part, “Per FPD policy, the officers were placed on administrative leave. The San Juan County Sheriff’s Office conducted an investigation into the incident; no charges were filed. Additionally, the district attorney’s office reviewed the investigation and did not recommend charges be filed. In addition, FPD’s Internal Affairs Division conducted a separate investigation and did not find the officers’ actions to be out of policy.”

Bruce Weigel’s 2002 death along a Wyoming interstate didn’t make national news either, but the legal case that followed it became a bit of a roadmap for any and all police officers working within the Rocky Mountain region.

Bryan Ulmer, a Wyoming attorney, worked the case on behalf of Weigel’s family.

“Bruce was traveling into Wyoming from Colorado,” Ulmer said. Shortly after entering Wyoming on Interstate 25, Weigel’s car hit a Wyoming State Trooper’s car from behind.

While questioning Weigel, the trooper reported seeing Weigel walk into oncoming traffic traveling on I-25.

“Concerned for the safety of Mr. Weigel and the public, Trooper Henderson followed Mr. Weigel, tackled him, and wrestled him to the ground in a ditch alongside the highway,” read a court filing in the case.

Another trooper joined in along with at least one other bystander.

Weigel was handcuffed and remained in a prone position. Shortly after, Weigel stopped breathing.

“He died because he was asphyxiated,” Ulmer said.

As Weigel v. Broad wound its way through the federal court system, the case largely hinged on what could or could not be considered excessive force.

In 2008, the U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals decided the prolonged restraint applied even after Weigel was handcuffed was ultimately problematic.

In a decision that still has implications today, the Court ruled, “Applying pressure to Mr. Weigel’s upper back, once he was handcuffed and his legs restrained, was constitutionally unreasonable due to the significant risk of positional asphyxiation associated with such actions.”

“As soon as the threat is removed, there is no need to hold someone down in a position that could kill them,” Ulmer said.