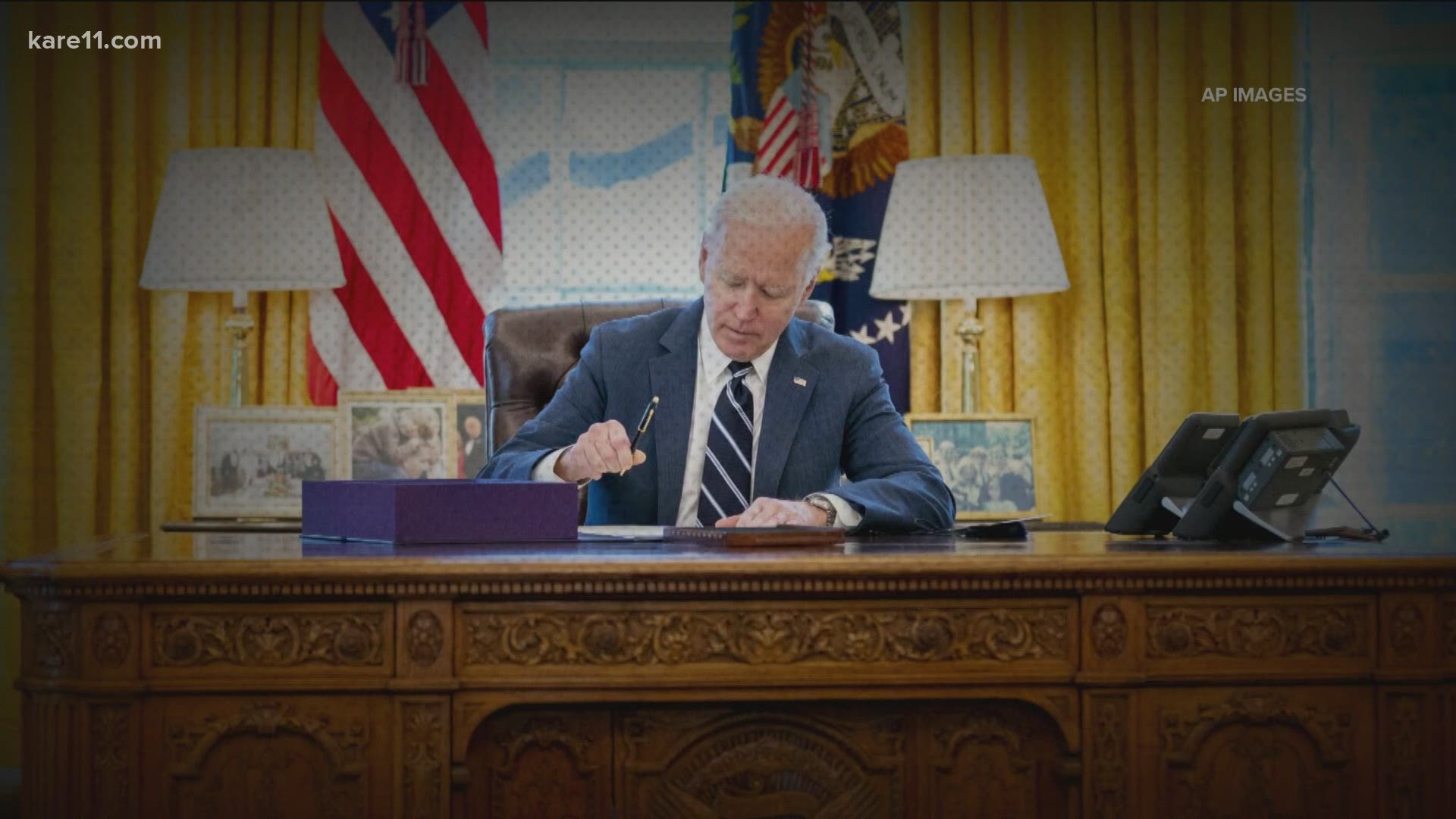

MINNEAPOLIS — The $1.9 trillion stimulus bill now signed into law by President Joe Biden, doesn't just contain $1,400 checks for many Americans and COVID-19 relief money for states and businesses. It also dramatically expands the child tax credit in a way that could have a major impact on child poverty.

"It really has the opportunity to be a transformation tool in the reduction of child poverty in America," said Barti Wahi, executive director of Children's Defense Fund Minnesota.

Wahi says the Children's Defense Fund and several other organizations have spent years advocating for an expansion of the child tax credit as a way to address child poverty directly.

Since it was first passed into law in the late 1990's the tax credit has been the largest federal expenditure to benefit children, there's just been one big caveat.

"The thing is that a third of children in the country were ineligible for the credit because their families didn't earn enough to qualify," said Sophie Collyer, Research Director at the Columbia University Center on Poverty & Social Policy. "So the largest federal expenditure made to benefit children was actually not reaching the children who would benefit from it the most."

Collyer says the new stimulus does away with that minimum income requirement, immediately expanding the credit to 26 million more children. It also increases the annual credit from $2,000 per child, to $3,000 for children ages 6-17 and $3,600 for children five and under.

Collyer and her colleagues at the Center on Poverty & Social Policy found that those changes would result in a 45% reduction in child poverty.

"And when paired with the other proposals and reforms in the American Rescue Plan, we see the child poverty rate falling by half," Collyer said.

Kent Erdahl: "That almost seems unbelievable."

Collyer: "It seems so, but the numbers are just showing that this correction for a real gap that was left in existing policy is a big part of the puzzle when it comes to addressing the high rate of child poverty in the United States."

In Minnesota, the report found the tax credit expansion would result in a 65% reduction in poverty, especially helping communities of color.

"Minnesota has a very low poverty rate nationwide. In 2019, we were at the seventh lowest poverty rate in the country," said Jose Pacas, a research scientist who specializes in child poverty at the University of Minnesota. "When we cut it by race and ethnicity, African American, Latino, Native American, we're looking at the top ten in the country."

Though Pacas is a research scientist, he says you don't need to be one to understand the premise.

"Find people who have children, find those who are in need, let's give them some money," Pacas said. "Poverty, as we've defined it in the US, comes down to almost a simple accounting exercise: How much income comes into your household each year, and we compare that to a poverty threshold."

Not only will the expansion push many families beyond that threshold, Pacas says the credit will be distributed in a more meaningful way. Beginning this summer, the money will be broken up into monthly payments. Parents of children five years and under will receive $300 each month for each child. Parents of children 6-17 will receive $250 per child each month.

"We have to pay the rent at the end of the month, not at the end of the year," Pacas said. "So cutting checks every month is something that's actually much better for those who are living paycheck to paycheck."

But the expansion isn't permanent, it is set to expire at the end of the year unless Congress votes to keep it going. Experts say that might be enough time to prove that it's worth every penny.

"I think a year is enough to show how beneficial it can be to families, especially as they receive their income on a month to month basis," Pacas said. "It's going to be hard for people to vote against it after they see how many people are being helped by this."

Though no republicans voted for the stimulus bill, there has been some level of bipartisan support for expanding the child tax credit. Senator Mitt Romney was among several republicans who have proposed similar expansions, but disagreements remain on how to pay for it long term.