Nurses, police, prosecutors, attend strangulation prevention training

According to Alliance for HOPE International, the most dangerous domestic violence offenders strangle their victims.

This weekend, friends, family and community plan to lay Maddi Kingsbury to rest.

Kingsbury's ex-boyfriend, Adam Fravel, is charged with her murder. In the charges against Fravel for Kingsbury's death are details of previous domestic abuse, including two instances when Fravel allegedly put his hands around Kingsbury's neck.

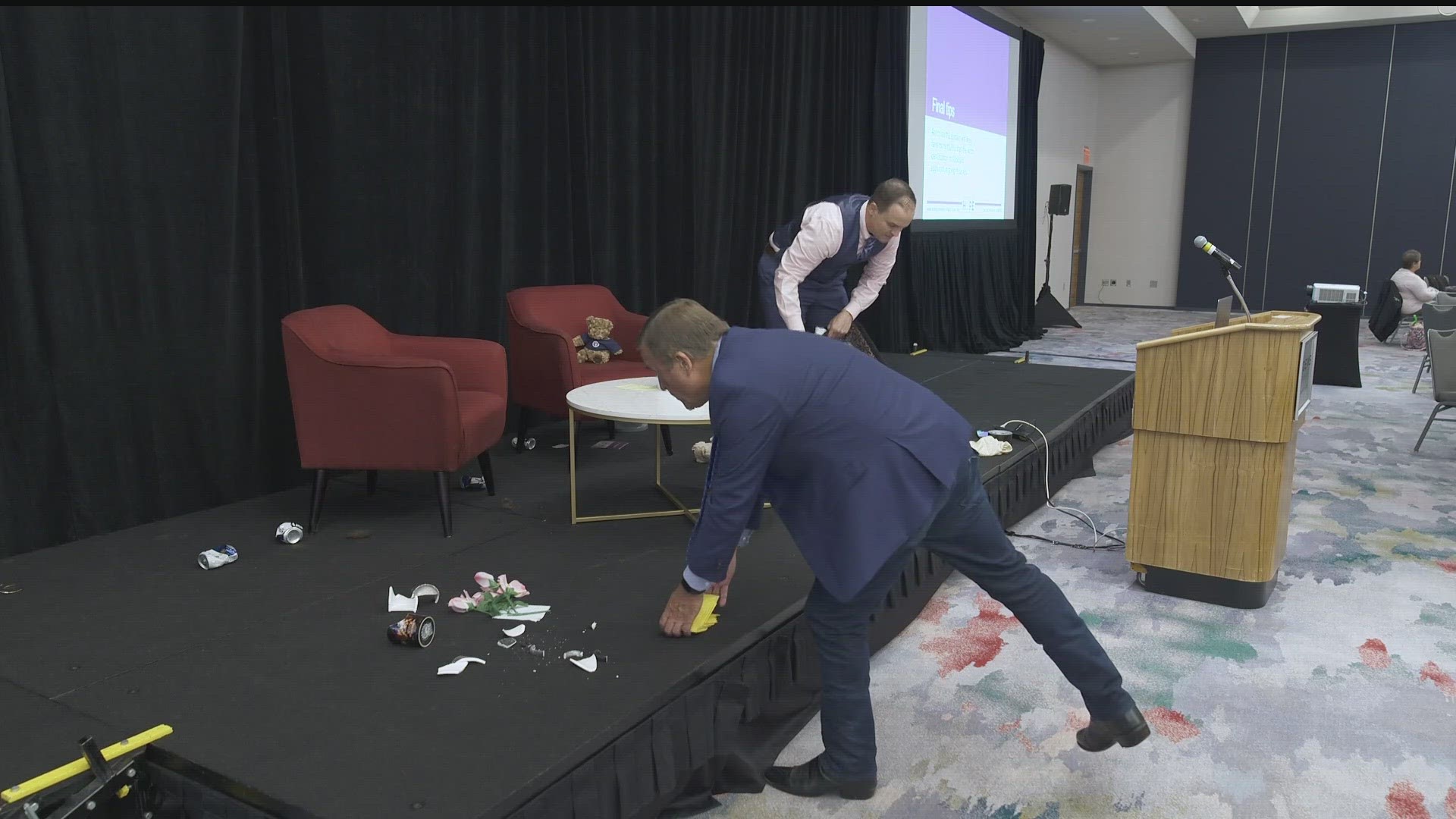

Strangulation is something so dangerous in the realm of domestic and sexual assault, it's the focus of a specialized training this week at Loews Minneapolis Hotel downtown.

About 100 professionals in the medical field, law enforcement and justice system are attending from across the Midwest, including forensic nurse coordinator Whitney Brothers, a St. Kate's graduate now working for hospitals in Montana and North Dakota.

"I'm in the hospital on standby if a patient comes in reporting sexual assault who needs a forensic medical exam," Brothers said. "We don't spend enough time learning about strangulation."

Those in her field say many patients don't initially report they were strangled during an assault. They say reasons can include shame or fear. Other times, survivors aren't aware they were strangled because the strangle didn't leave a mark. However, doctors say even no mark can mean long-term health problems and even death weeks or months after the event.

"Some people don't realize what's happening to them," Hennepin Healthcare forensic nurse examiner Breanna Heisterkamp said, "and how close they are potentially to death."

Heisterkamp is also a nurse manager for Hennepin Healthcare's Hennepin Assault Response Team and director of a three-year, $1.5 million federal grant from the Health Resources & Services Administration.

Meanwhile, project coordinator Stephanie Ellis organized the weeklong training, which involved flying in experts from Alliance for HOPE International and their Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention.

"We started to do this work as a result of two teenagers dying in San Diego back in 1995," Alliance for HOPE International CEO and cofounder Gael Strack said. "At the time, I was in charge of our child abuse and domestic violence unit and these two teenagers both separately called the police to report that their ex-boyfriends had just choked them."

"Neither one of those cases were prosecuted," she continued. "So then it started a long journey to try to figure out: how did we miss this, why did we miss it, and what do we need to do to fix it?"

Extensive research led them to learn patterns of people who strangle.

"Years ago, we thought that the man who punched a woman, slapped a woman, choked a woman, they were all the same and then we figured out in our research, the men who slap or punch women, they're idiots," Alliance for HOPE International president Casey Gwinn said. "Men who strangle women are killers. They're not the same. The rage of a man who goes after a woman's neck turns out is the same kind of rage that ends up killing a police officer … The same kind of rage that kills children. The same kind of rage that motivates mass shooters across America."

And so one takeaway from the training is to ask survivors the right questions, they say, because the more documentation the stronger the evidence against a dangerous person in court.

"'What did you think was going to happen?' That's a question I don't often ask," Brothers said. "Then also, 'What made it stop?'"

"To be able to come to a more specialized, specific training for strangulation will just help to add more tools in our toolbox and take care of patients and provide them with the best care that we can."

The training was made possible because Hennepin Healthcare secured a three-year, $1.5 million federal grant through the Health Resources & Services Administration.