MINNEAPOLIS — When David James saw the news last week that Minneapolis Police had killed 22-year-old Amir Locke while executing a high-risk search warrant entry, the president of the Louisville Metro Council immediately thought of Breonna Taylor.

“Oh, absolutely,” James said. “It just brought back a lot of memories.”

James, a former police officer, oversaw the council’s unanimous vote in June 2020 to pass Breonna’s Law, just a few months after the Louisville Metro Police Department shot and killed her during a raid. That legislation specifically banned no-knock warrants, implemented further restrictions on all types of warrants, and added a body camera requirement for warrant executions.

In the year and a half since the Metro Council passed that measure, James said he has not heard any complaints from law enforcement or prosecutors, although some did voice opposition to the rules in the beginning.

“That was a tragic time. There was a lot of emotion involved with the council members and the community,” James said in a Zoom interview. “The police, at that time, were saying, ‘well, [if] we can’t do no-knock warrants, we can’t ever catch criminals.’ So, we really talked through that…The fact that we had a young lady, through no fault of her own, dead because of a police action, it really outweighed everything.”

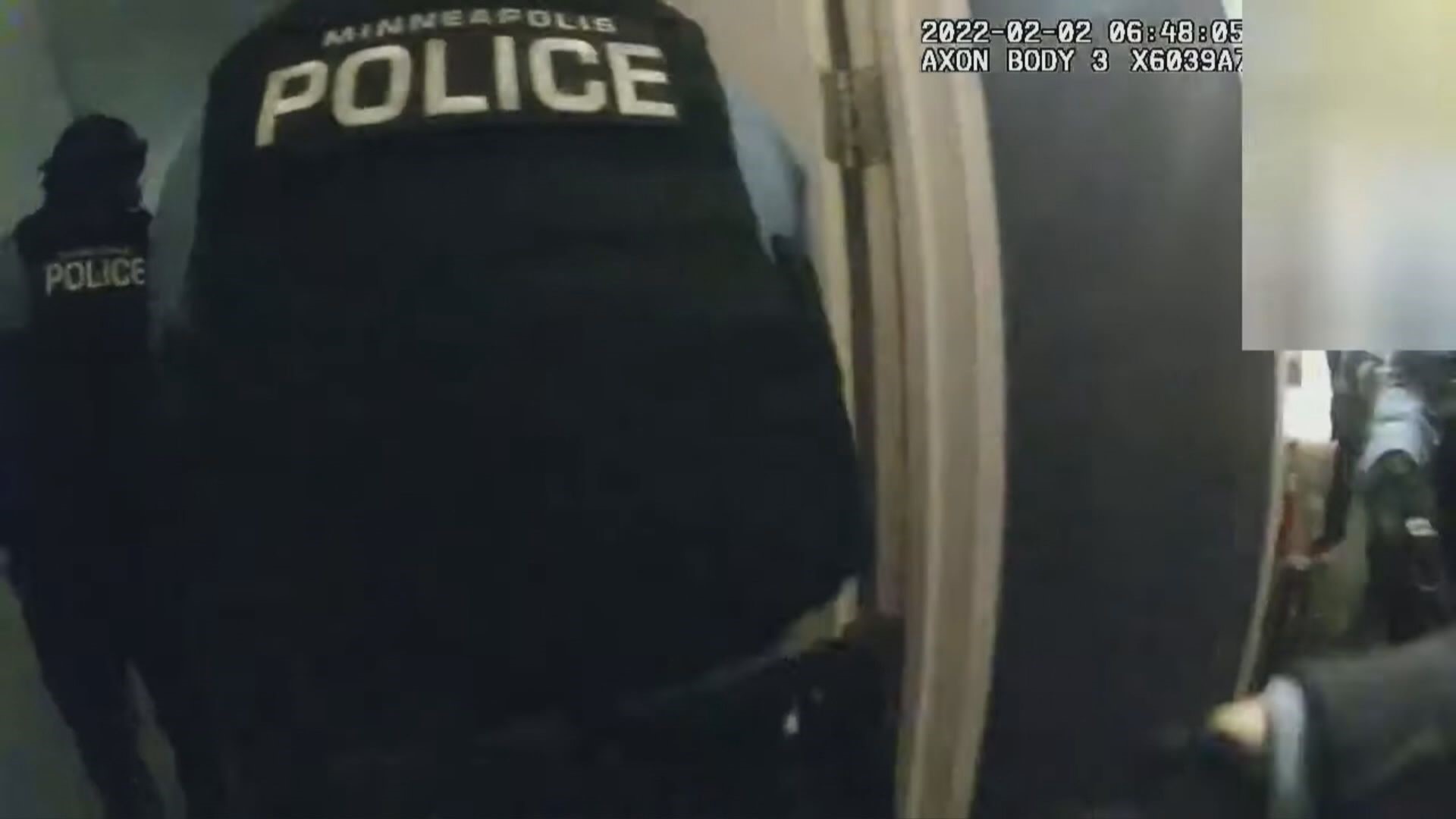

Following Locke’s killing, Minneapolis may now look to Breonna’s Law as a model for its own policy moving forward. Mayor Jacob Frey’s administration has announced a temporary moratorium on requesting and serving no-knock warrants, with limited exceptions as approved by the police chief in the event of “imminent harm.”

While the temporary ban remains in place, Frey has recruited prominent Campaign Zero co-founder DeRay Mckesson and Eastern Kentucky University criminal justice expert Dr. Pete Kraska to consult with the city about long-term policies. The mayor said he chose Mckesson and Kraska because they “helped shape Breonna’s Law in Louisville and have spearheaded significant reforms to unannounced entry policies associated with no-knock warrants in state across the country.”

Mckesson, a former Minneapolis Public Schools senior director, rose to prominence as an activist after Ferguson. His Campaign Zero rubric, which pushes for reforms to both no-knock and knock-and-announce warrants, rates the city’s current policies as a 5.5 out of 15.

“To the citizen, the impact [of either type of warrant] is the same. You’re asleep in both of them and really had no opportunity to reply or respond, so what we built is a rubric that helps cities change the policies in ways that limit the police to do those things,” Mckesson said. “The warrant type doesn’t matter as much as people think it does.”

It is not clear how far the mayor’s office or city council will go in restricting all types of warrants, nor has the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis made its stance known about these ongoing efforts. Last year, the city of Minneapolis started requiring officers to announce their presence before entry in most no-knock situations, but Mayor Frey’s administration did not completely ban them at the time.

In the past year or so, Mckesson said that six states and a handful of cities have banned or restricted no-knock warrants, ranging from Santa Fe, N.M., to St. Louis, Mo., to Pittsburgh, Pa.

The trend started, of course, with Louisville.

“I think the changes in Louisville are so new,” Mckesson said, “that we’re still trying to track the impact.”

Shortly after the Metro Council issued that unanimous vote in June 2020, council president David James said: “Our action tonight sets an example for other cities to follow.”

He stands by those words.

“If [law enforcement] did come back and say, ‘hey, we need to modify it,’ or, ‘can we try this,’ we would look at it and talk about it and see what could be done,” James said. “But no one has approached us at any point to say that it’s a problem.”