There seems to be consensus on George Floyd's death: it was wrong.

Floyd died on May 25 in Minneapolis after former officer Derek Chauvin had his knee on Floyd's neck for more than eight minutes.

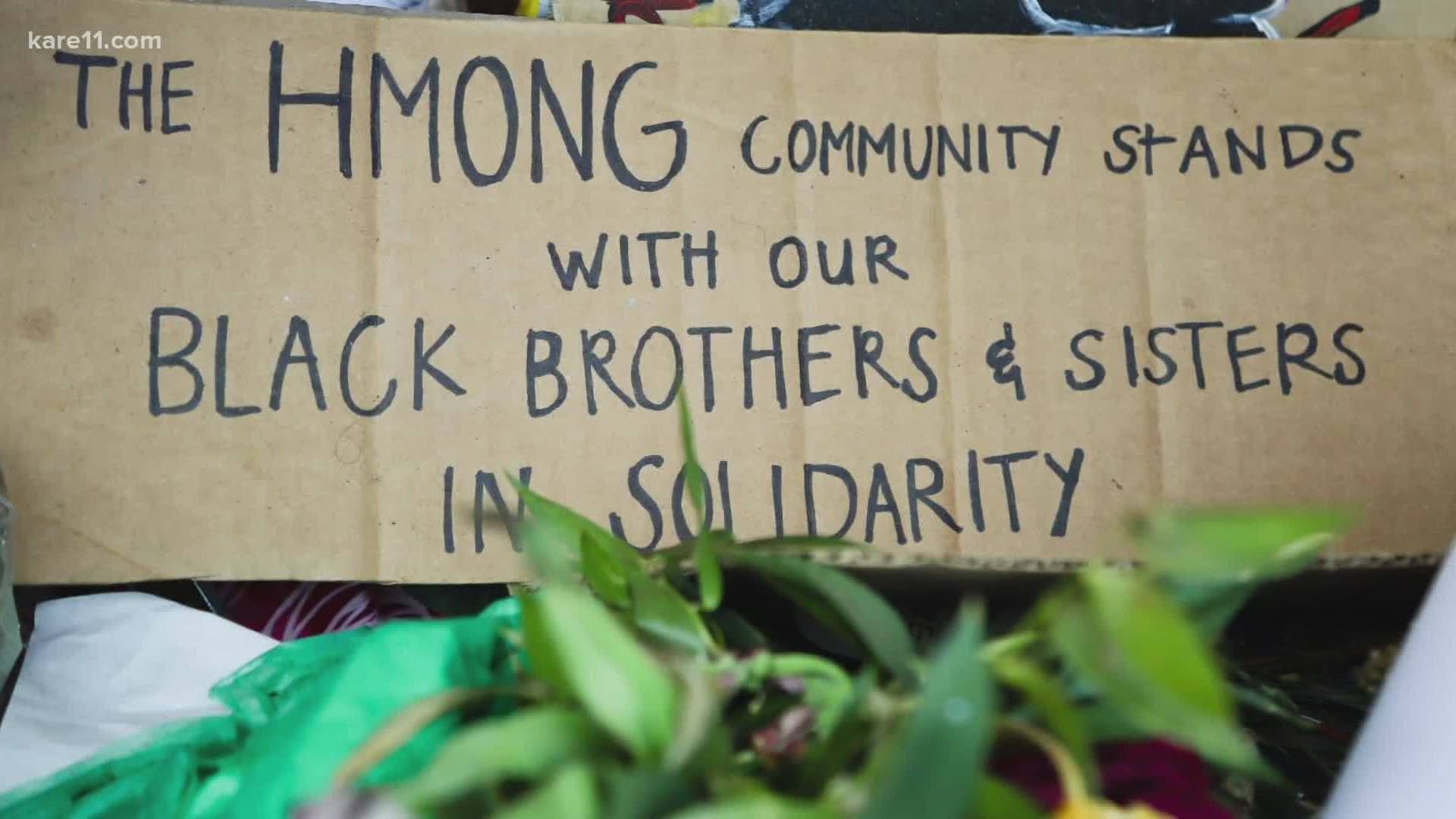

But where conversations start to split, at least in the Hmong community, is involvement in the protests to demand justice and change in the system. The debate is complicated by the fact, Tou Thao, one of the officers involved in the death of Floyd, is also Hmong.

The division seemed apparent when one Hmong family, along with other Hmong people, decided to join the protest at the Minnesota state capitol after Floyd's death.

"When my son died they came out and supported me," Youa Vang said in Hmong. "They talked with me, they protested with me and us and anything that we asked them to be in solidarity with us in, they were," she said.

Vang is talking about Black Americans who supported her and her family after the death of her son Fong Lee. Her son was 19-years-old when he was shot and killed by a Minneapolis police officer in 2006. The officer said Lee had a gun on him and feared for his life, before shooting Lee multiple times.

Lee's family didn't buy it and took it to court in 2009 in a wrongful death lawsuit. Among their claims, a questionable investigation and evidence planting. But the court didn't agree with Lee's family, leaving them in what they consider a purgatory of injustice.

Vang said the death of her son and the injustice she felt afterward, is a sorrow she never wishes on anyone. That's why she and her daughter Shoua Lee said they can understand the pain of the Floyd family and any other families that have loved ones who have died from police brutality.

"We feel like if there's justice for George then there will be justice for us," Lee said. "For everyone else for the future, for our kids," she said.

RELATED: Having hard conversations after the killing of George Floyd? Here are tips to make them effective.

Lee's family's presence, along with other Hmong at the protests, thrust the community into taking a closer look at the Hmong's history with black Americans.

Vang said she knows some Hmong are hurt by the bad experiences they've had with black people when they first arrived in this country.

"But good and bad people come in all colors," Vang said. "We love each other in the Hmong community, but there are some who haven't thought about how the black people's Civil Rights Movement carved a path for us to live our lives," she said.

The issue of anti-blackness in the community are complex. Bo-Thao Urabe is the executive director of the Coalition of Asian American Leaders and Chris Her is a new advocate in the community. They're responding to some of what it's being said. To be clear, anti-blackness is not unique to the Hmong community and this is not an exhaustive list of arguments, but it addresses some common themes heard to see if there is a point of understanding.

So, what if someone says, it's the black community's fight, not ours?

"The reason why a Hmong person could be killed every few years by the police stems from the same system that kills black people everyday just about and so that's why it's our fight," Thao-Urabe said. "It's all of our fight because if that were to happen to me I would want all of you to fight like hell to get justice for me," Thao-Urabe said.

Some in the Hmong community say they grew up poor, or as refugees or the children of refugees, and they have been able to create opportunities for themselves. Why can't everyone?

"I don't think people should be comparing our own sufferings at all," Her said. "I think that when it comes to suffering we all experience it differently." He said there are different circumstances when you look at the bigger picture.

Thao-Urabe added, "Unfortunately throughout American history there have been so many attempts to pit Asian Americans against Black Americans and so that tactic is meant to distract us from being able to work together to really root out racism."

Some also want to distance themselves from Black Lives Matter protests, thinking they are connected to violence, looting, and destruction of property and aren't the best way to communicate a believed oppression.

"When people are trying to kill us or take away our liberties, we have fought back, right? So I think it's important for us, to not take us out of that picture of understanding what uprisings are about and what it means to really be fighting for your life," Thao-Urabe said. She adds, it's not our place to tell another community how to fight.

What if someone says 'all lives matter'?

"I think that's what everyone is saying, all lives should matter," Thao-Urabe said. "But right now when we look at what is happening black lives don't matter," she said. "If we look at systematically who dies at the hands of police and especially those who are killed who are unarmed and things like that, it's disproportionately black people," Thao-Urabe said.

A 2019 report by Mapping Police Violence organization said black people were 24% of those killed, despite being only 13% of the population. The report also said from 2013 to 2019, black people are 1.3 times more likely to be unarmed, compared to white people.

"You have to be able to take a step back and realize, 'What kind of space am I taking up when I make that statement and what kind of attention am I taking away from the real matter here?'" Her said.

There are even nuances between the Hmong ethnic group and the larger Asian community. Thao-Urabe said the Hmong are fairly new as an Asian American group. But she said the history in this country is one of racism when it comes to Asian Americans.

"We are one of the first groups to be excluded for coming to the U.S. and that happened in the Chinese Exclusion Act and then the Japanese internment and then 9/11 happened and a lot of our south Asian brothers and sisters were detained," Thao-Urabe said. "Now the Muslim ban and all of those things, so there’s so many intersections and I think when we tend to zoom in and make it very personal, we might not see the big systems things," Thao-Urabe said.

But Thao-Urabe has hope. She said solidarity is the way forward reminding people of color that their liberation is tied.

"Where we fall as Hmong people is going to matter and so do we want to look back and say we were part of causing that change or do we silently sit by and where I'm hopeful is that there are many more people who are not just silently sitting by," Thao-Urabe said.

That includes people like Her, who said he felt compelled to be active for the first time.

"It was just it was heartbreaking just to hear about George Floyd," Her said. "I felt like it was my social responsibility to really step in and put a voice in the community and say it is not OK," he said.