GOLDEN VALLEY, Minn. – What does a heroin addict look like? As heroin abuse reaches an unprecedented level in Minnesota, the epidemic touches your neighbor, co-worker or can even take hold in your own home.

The number of people entering treatment for heroin addiction in the Twin Cities reached a historic high last year and more people are getting treatment for heroin now than marijuana, according to the Minneapolis/St. Paul Drug Abuse Trends report, by Carol Falkowski.

WATCH the story here: http://kare11.tv/1SZbSR9

In the report, she noted the largest group of those entering treatment for heroin are white men in their 20s.

Minnesota law enforcement are seeing another toll, taking 18 pounds of heroin off the streets last year, more than $1 million dollars’ worth, a record that soared three times the amount of heroin seized in 2012.

The gravest toll is the void left behind, as more potent heroin circulates across the state, leading to deadly overdoses. In Dakota, Scott and Hennepin Counties in 2015, 53 people died from heroin overdoses.

In Northern Minnesota, in March of 2015, heroin overdoses killed seven people and put dozens more in the hospital across Hibbing, Detroit Lakes, Cass Lake, and other northern Minnesota communities.

KARE 11 profiled three Minnesota families who understand the loss. Still deeply grieving, parents who have lost their sons to heroin agreed to come forward to prevent others from the same heartache.

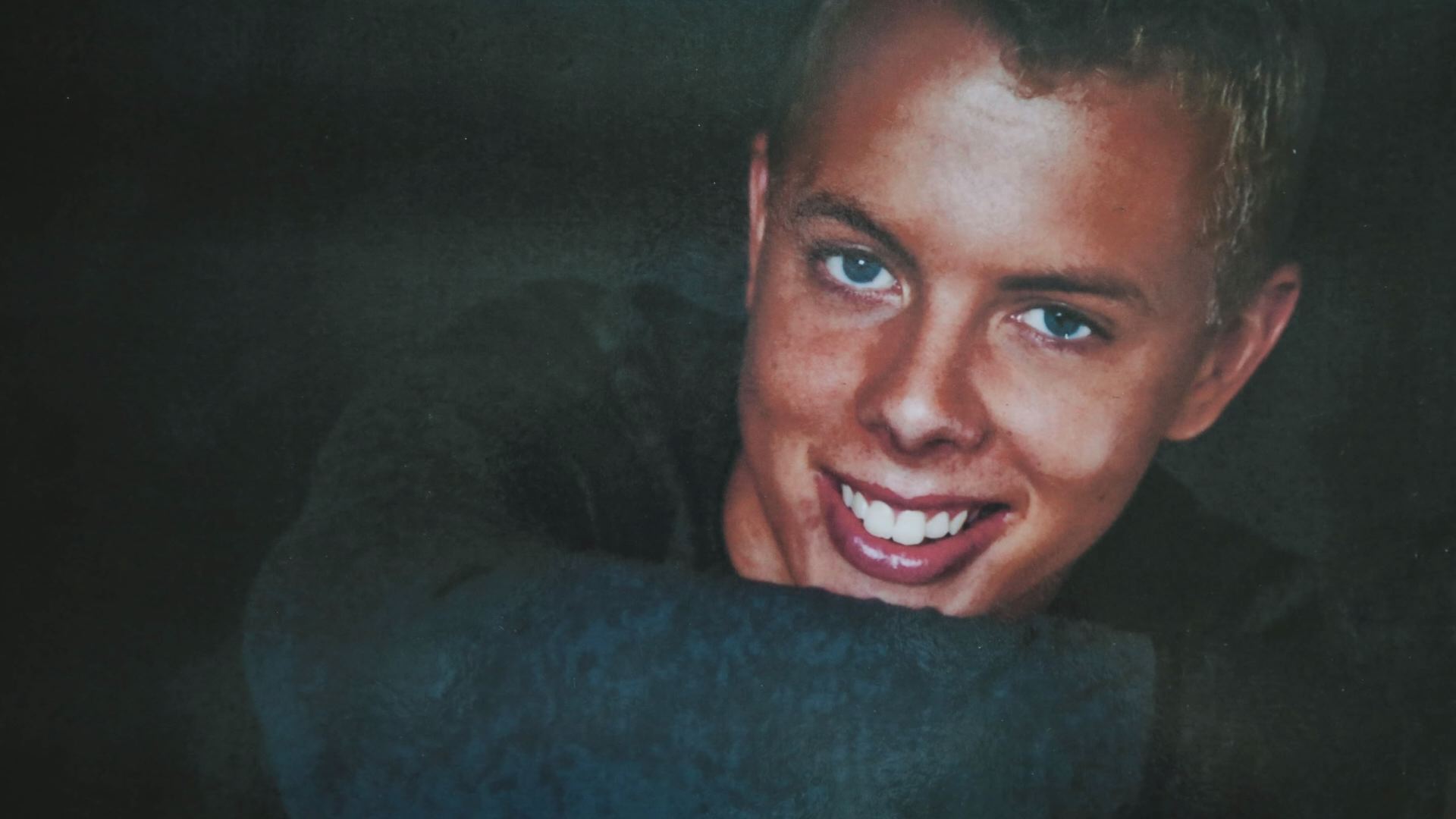

Dylan Pearson

Dylan Pearson, 19, of St. Francis, Minnesota just returned from a drug treatment program in Florida. On January 31, 2015, he had been home two weeks when his stepfather found him dead in his bedroom.

More than a year later, his Air Jordan tennis shoes still sit right where he last took them off next to the couch. His jacket still hangs on the banister. His mother, Jennifer Nordeen, can’t bear to move his belongings, still haunted by her husband’s screams that January afternoon.

"I found him laying here," said Andy Nordeen, standing over Dylan's bed. "He looked absolutely perfect laying here. I put my hand on his chest and stomach and could tell he was cold and stiff and that is when I screamed."

“I called 911 and just went and held him and touched his face and asked him to wake up,” said Nordeen.

A year later, in her grief, Nordeen has started a non-profit organization, Free Heroin’s Hold, in her son’s memory, to fund treatment programs for others struggling with addiction. She holds a weekly support group for families struggling with heroin addiction and also copes by visiting her son’s grave daily.

Dylan began experimenting with drugs in high school, and his addiction quickly ramped up towards heroin use. He underwent several treatment programs.

“I still can’t believe it happened to us because I was the most involved mom there is. You can still be involved but it doesn’t make a difference,” said Nordeen. “He knew how much I was in love with him and did everything I could and still couldn’t save him. I can’t let his name go for nothing. This is senseless. This is a senseless death.”

Ryan Abrahamson

Ryan Abrahamson, 28, grew up in the Hopkins/Minnetonka area and spent his last years of life working at a camp in Northern Minnesota in the summers and spending his winters working in California.

He overdosed in a North Minneapolis home on October 27, 2014. It took deputies more than 24 hours to track down his mother, Patty Moe, and stepfather, Brad Sundquist, who now live near Marshall, Minnesota.

“Two 20-year-old deputies in tears. It was probably the first time they had to make that kind of call,” recalls Moe. “They found him with his license and a quarter in his pocket and that’s it. It was devastating it really was. Honestly, I think you go into shock.”

Moe said she knew her son had struggled with heroin in the past, but said he was recently determined after several months of sobriety and wanted to overcome his addiction marry his longtime girlfriend.

“It wasn’t who he was. Doing heroin wasn’t who he was,” said Moe. “He was so smart, he wanted to be a writer. So you never imagine he would grow up to be a drug addict, you wouldn’t want that for him and don’t expect it, never dreamed of it.”

Abrahamson began experimenting with drugs in his teenage years, and struggled with addiction ever since.

He left behind an entry in a tattered journal that gave clues to his decline, written in the months before his death.

“The sound of loons is beautiful, the ocean is good for me, and always camp is the most magical place I’ve been and will ever be. I love loving people, sometimes it is best to be lost,” wrote Abrahamson.

Moe and Sundquist want to tell their son’s story to dispel the stigma of addiction, a pull they also understand. Both became addicted to painkiller pills after medical procedures, but after treatment and intervention, have been sober for a decade.

“It shouldn’t be a shame issue, if people truly believe addiction an illness, are you ashamed to have diabetes or a heart issue?” said Sundquist.

“Here is the deal, if nobody talks about this, how is anybody going to get any help? My pride lies in helping other people,” said Moe.

Moe herself confessed to turning to heroin once when she couldn’t get access to any more painkillers. She said she overdosed and was saved by naloxone, often referred to as the brand name Narcan, used to reverse the damage from heroin or an opiate prescription painkiller overdose.

“And then all these years later, we couldn’t save our own son,” said Moe.

Alex Milun

Alex Milun, 24, of Medina was often described as “sparkly” by his teachers, whether at Wayzata High School or in Sunday school.

“That seemed to be a theme through his life, he shined. He just had a certain something,” said Kirsten and Dick Milun, his parents, of Corcoran.

Alex enrolled in college in South Dakota and after some struggles returned home to Minnesota. Kirsten Milun said he confessed to a painkiller addiction two days before his death on October 24, 2015. She didn’t know he was using heroin until the day he died, when his younger brother found him dead from an overdose.

“That’s when we knew, but the signs were there, believe me. We passed it off as something else, I can’t even believe it,” said Milun. “There are a lot of reasons a parent may not know. We were treating him for a PTSD type thing.”

Milun said her son often nodded off, falling asleep in an instant. His attitude changed, and his money disappeared.

“He wouldn’t want us to think of him that way. He’d want us to think of him fishing and happy, and no one would have been more pissed off than Alex Milun with what he had done and he paid the ultimate price,” said Milun.

In mid-April, U.S. Attorney Andrew Luger announced a federal indictment charging suspected drug dealer, Jaime McClellan, with distributing the heroin that led to Milun’s death.

Court documents say McClellan sold heroin to Milun on October 23, 2015 and warned him to be careful while using the heroin that night because it was “good stuff.” When authorities arrested McClellan in December of 2015, they found 15 grams of heroin on McClellan along with $400,000 in cash.

Now trying to grasp the federal court case while still deeply grieving, Kirsten Milun said all the memories of her son have made her home a museum, equally a “house of horrors” and a place of comfort.

“Sometimes you are pouring cereal and I think oh my God, my kid is gone, he's never coming through the front door again. He is so alive here running down that staircase, with his bright little shining face with his brother and sister. My son is at the fireplace. My son is sitting here watching Christmas movies with me, he sitting over there eating popcorn and laughing, and in all of this he is living and yet he’s in a box over there,” she said, pointing to his ashes under a side table.

A mother can never forget a tormented final goodbye that came far too soon, within the walls of a morgue.

“I just remember hugging him with this ice. Those beautiful lashes he had as a baby, the same ones, only he’s dead, you know? So I sang to him what I used to sing to him as a baby, Mr. Rogers’, “It’s You I Like.”

It's you I like,

It's not the things you wear,

It's not the way you do your hair--

But it's you I like.

The way you are right now,

The way down deep inside you--

Not the things that hide you,

Not your toys--

They're just beside you.But it's you I like--

Every part of you,

Your skin, your eyes, your feelings

Whether old or new.

I hope that you'll remember

Even when you're feeling blue

That it's you I like,

It's you yourself,

It's you, it's you I like.

For information and resources on how to get help for heroin addiction, click here.