ST PAUL, Minn. — Boxes are stacked in a back room in the library of Concordia University in Saint Paul.

"This is all of his stuff that we have to sort through," Lee Pao Xiong said. He's the director for the Center for Hmong Studies.

The boxes all have one name on it: Rosenblatt. "I think without Lionel Rosenblatt we wouldn't be here," Xiong said.

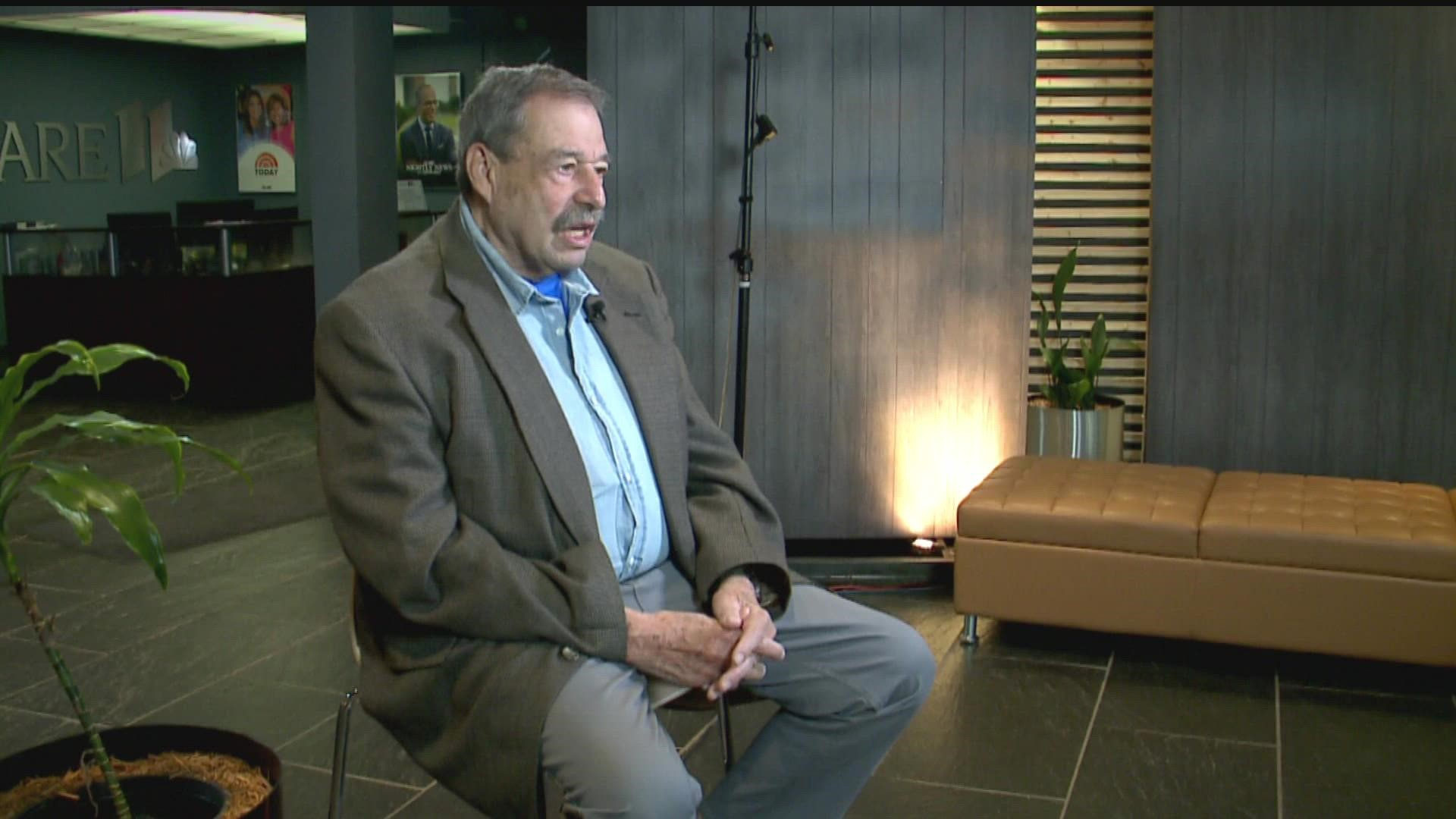

"I was refugee coordinator based in the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok," Lionel Rosenblatt said.

Rosenblatt was a foreign service officer in the 1970s when the U.S. allocated 150,000 Vietnamese to resettle here after the fall of Saigon. Some of the spaces allocated for refugees remained unused, so Rosenblatt went to find those left behind.

"I made the case to the bureaucracy, actually to Henry Kissinger, that we ought to use the remaining 11,000 on refugees who had come out to Thailand, from Laos, and Cambodia," Rosenblatt said. "I was armed with ESO road map and an embassy driver and put a tie on him," he said. "We bought a couple of cases of scotch and talked our way out to the various border camps and did a complete interview of everybody that had come in."

On his last day, he ended up learning about the Hmong through Jerry Daniels. Rosenblatt became the liaison officer between General Vang Pao of the Hmong and the CIA, and MacAlan "Mac" Thompson who also worked with the Hmong through the U.S. Agency for International Development. Rosenblatt learned just how much the Hmong worked with U.S. forces under the CIA during the Secret War.

"I spent three hours at Nam Phong Camp and with Jerry and Mac and I was just blown away by the fact that the Hmong were very closely integrated with the U.S. forces, many of them with U.S. call signs like 'Hammer' and 'Snowball' and 'Lucky' and 'Bison' and I said to myself 'These are people we owe and they would be at the top of any list of people closely associated with the U.S. government," Rosenblatt said.

But the Hmong weren't part of the resettlement stream.

"It was always a mystery to me why they were good enough to fight for us but not good enough to consider for resettlement," he said. "We just knew that there was a bias against resettlement for the Hmong."

That meant Rosenblatt said they didn't use the word "Highlanders" in resettlement documents, a word used to refer to the Hmong people.

"And that's how we kind of disguised our early moves," he said.

But Rosenblatt points out, the Hmong coming into Thailand weren’t shopping for resettlement.

"They wanted to stay together and it was interesting, they were the only group that was thinking about what's best for us as a group and they came to us with several choices," Rosenblatt said.

He sat with clan leaders in the Ban Vinai refugee camp. He said the leaders initially wanted weapons to retake and defend a southwest portion of Laos and an area west of the Mekong River. They also offered a choice of having a place in Thailand where they could be secure and defend themselves there.

When none of those were viable options for the U.S. government in it's capacity, Rosenblatt said they offered to come to the U.S. only if they could stay together on land, any land as remote as parts of Alaska and much like indigenous groups. Rosenblatt said they also couldn't do that.

But he finally explained about secondary migration in the U.S. where the Hmong would have freedom to move around. Only then, Rosenblatt said, were the Hmong willing to resettle in the U.S.

Lists were made from paper and pen, and in total 5,500 families initially came from Laos.

"Here's the original list with General Vang Pao's signature," Xiong shows us at the Center for Hmong Studies.

"It helps us reconnect the dots," he said. "We are here, how did we get here, and how do we ended up here?"

Some of those answers are in Rosenblatt's boxes.

"The point is that given opportunity, this country is still amazing in the way it can bring out human potential from people around the world," Rosenblatt said. "And it's an inspiring example for us as well as for other countries to see and we ought to continue to do that, we need that kind of fresh blood and energy in this country."

Watch the latest coverage from the KARE11 Sunrise in our YouTube playlist: