ST PAUL, Minn. — At barely a day old, newborn Ny'aire went through what most babies in Minnesota do shortly after birth: Getting his blood spotted for the state's newborn screening panel.

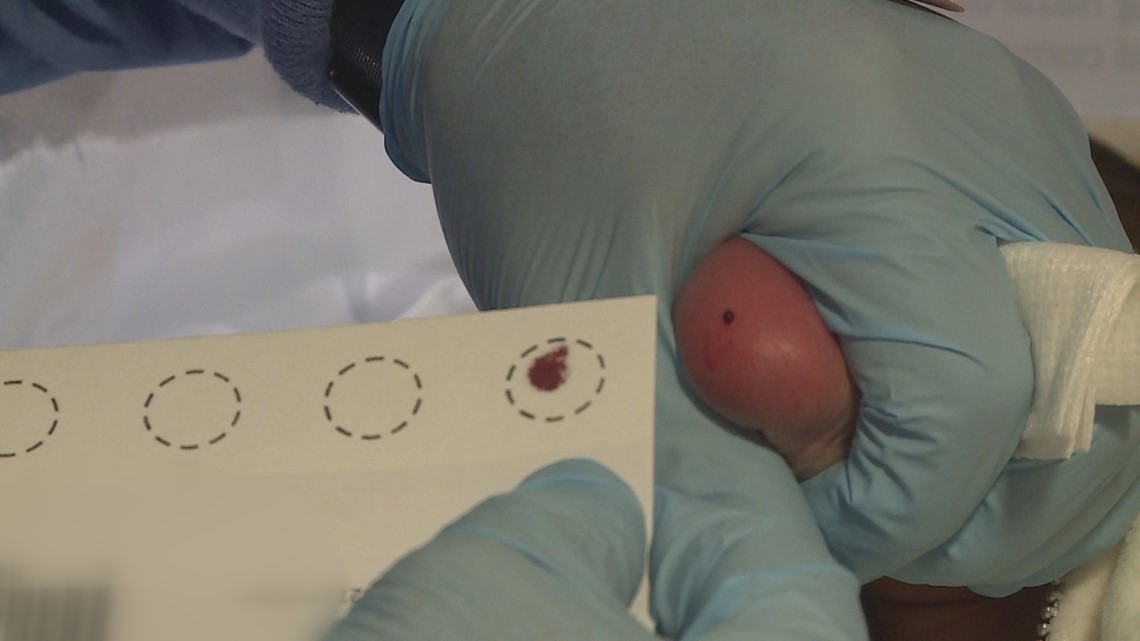

With mom and dad by his side at M Health Fairview Southdale Hospital, Ny'aire barely made a sound as his pricked heel was placed on a paper to smear his blood sample, which would then be sent to the Minnesota Department of Health.

But Ny'aire is among the first babies in the country to be universally screened for congenital cytomegalovirus, known as CMV. In February, Minnesota became the first state in the country to universally screen for CMV, after the 2021 passing of a law named the Vivian Act.

Cytomegalovirus is a common virus, frequently going undetected in adults and older children. However, if a pregnant woman contracts it and transfers it to her unborn baby, it can lead to developmental issues later on in the child's life.

Ask Leah Henrikson, mother of now 8-year-old Vivian Henrikson, for whom the Minnesota law was named.

"She already lost hearing at birth in her left ear, but she could also lose hearing in right," Henrikson said. "So we have to kind of monitor and lots of doctor's appointments and things."

Henrikson says in addition to hearing loss, Vivian has cerebral palsy, epilepsy and learning challenges.

Vivian contracted CMV in utero. Henrikson credits doctors with realizing something was wrong, leading Vivian to be diagnosed with CMV while just a few days old.

The early diagnosis allowed the Henriksons to plan and prepare for Vivian's potential health issues, something that Henrikson wants all families to have.

"It makes all the difference in the world to know right away," she said. "Early is always better for treatment... there are options, but if you don't know, you can't treat what you don't know. So then you've missed your window and it's hard to make up that valuable time."

The Department of Health estimates that of the 65,000 babies born each year in Minnesota, up to 300 will be born with CMV. Of that number, 20% will develop symptoms.

While that may not seem like a lot, the health department says the virus is more prevalent than some of the other disorders for which it screens.

"Some of the other conditions we might see one or two per year for those rare conditions, but with this, we do expect to see quite a few more positive results," said Jill Simonetti, manager of MDH's newborn screening program.

A component of the Vivian Act is education about CMV.

Many women have never even heard of the virus, let alone know how it spreads -through bodily fluid.

"So you might think twice before you finish your child's sandwich, for example. Or not share a cup with your toddler, because the virus is transferred through saliva," Henrikson said.

Dr. Mark Schleiss, a Professor of Pediatrics at the U of M Medical School who has long studied CMV, continues to research a possible vaccine for it. He supports the newborn screening, citing the importance of early intervention.

"The window for intervention, especially hearing loss, is really narrow," he said. "If a child has undiagnosed hearing loss in the first three years of life and they don't get early intervention, then their speech and language development can really be impaired in the long term. So it's an important diagnosis to try to identify."

Watch more KARE11 Sunrise:

Watch the latest coverage from KARE11 Sunrise in our YouTube playlist: