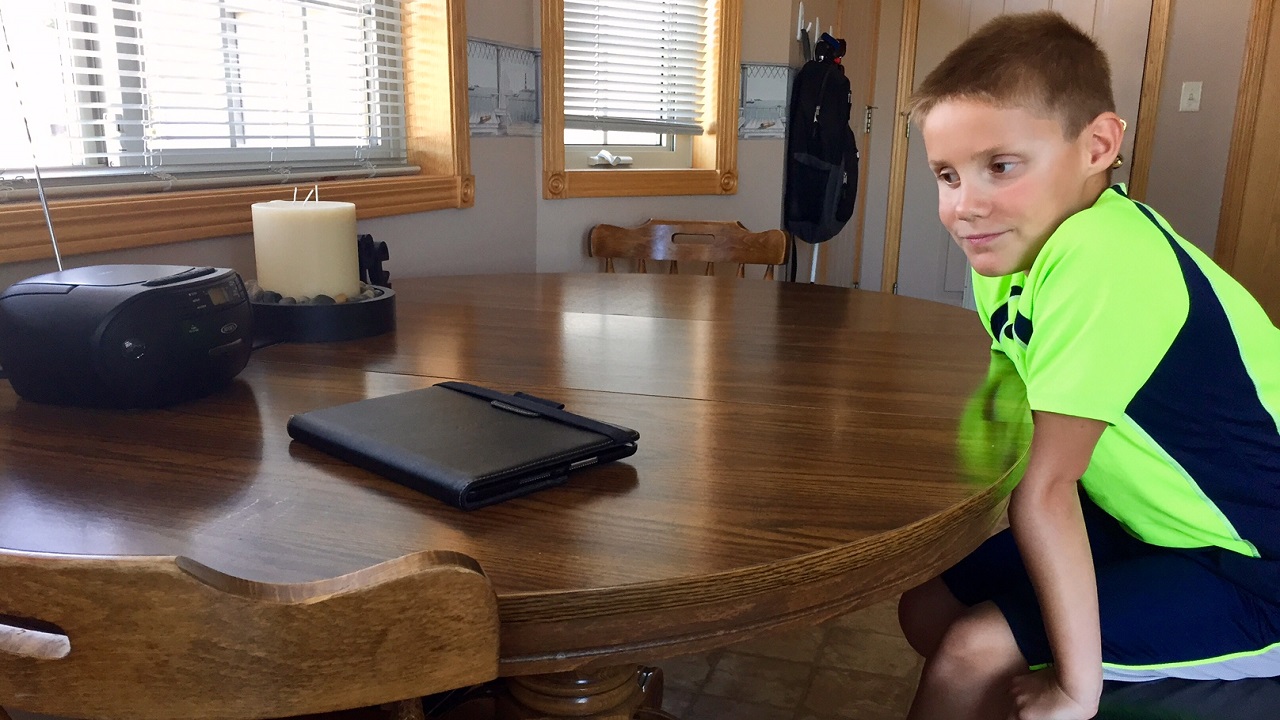

ALBANY, Minn. – He’s already finished his morning pancakes, but 8-year-old Riley Spindler lingers at the kitchen table.

“Small Town Boy Like Me from Dustin Lynch,” Riley gleefully announces, as the first notes of the song waft from the radio perched in front of him.

Then Riley cups his head in his hands, taps his feet to the music and studies every loving country note.

“This is every morning,” Riley’s mother, Arin Spindler, says with a laugh. "This is the 'morning motivator,' he calls it.”

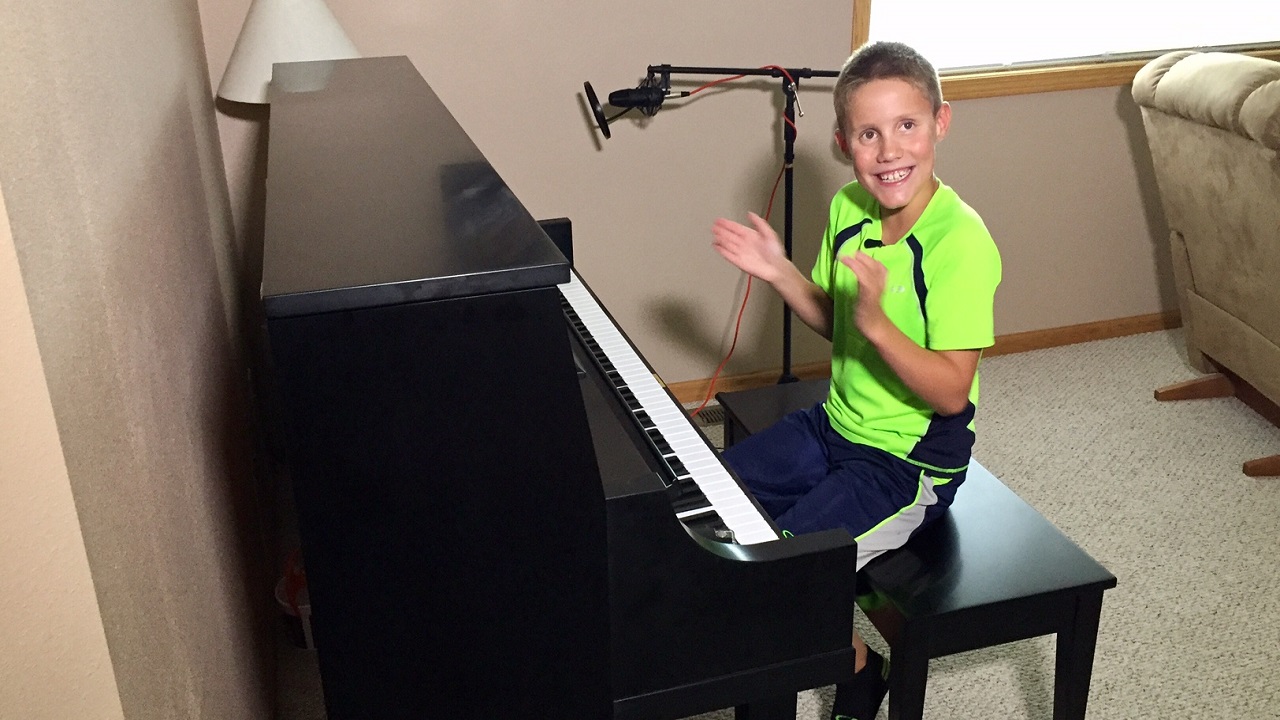

Brothers Osborne, Florida Georgia Line and an assortment of other artists follow. Riley intently takes them all in. Then he walks upstairs, seats himself at the piano and plays the music he’s just heard on the radio.

“You kind of put the notes together and then you make a song,” says Riley nonchalantly, as if he’s completed a minor task like opening a can of soda or folding a paper airplane.

In truth, every word and chord of every song Riley plays has been worked out in his head and committed to memory.

Riley doesn’t read music. He can’t.

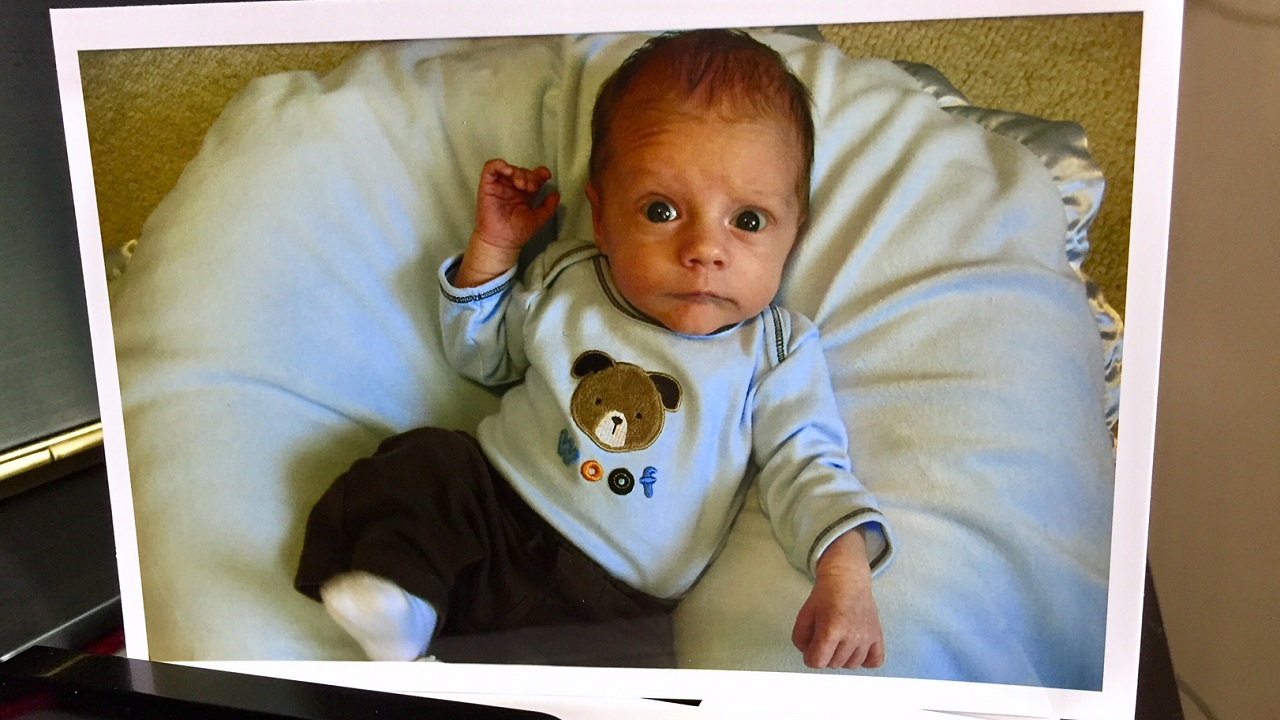

“At three months we knew something was wrong,” says Riley's mother, Arin Spindler. “Something wasn’t right with his eyes, he didn’t focus.”

Riley was diagnosed with a genetic disorder called Leber congenital amaurosis. He’s been blind since birth.

“It’s just that grieving,” says Arin Spindler, looking back. “You just feel like it’s the end of the world.”

It turns out the diagnosis was just Riley’s first stanza.

“Here we go, turn it up!” Riley shouts as he launches into a rousing version of “Ain’t My Fault” by Brothers Osborne. Riley pounds keys, claps, whoops, sings and never stops smiling.

His mother smiles too, thinking about the sympathy that sometimes comes her way in public.

“You have a lot of people who come up to you and just say, ‘Oh I’m so sorry, it must be awful.’ Her smile turns into a laugh, “And I’m like, ‘No it’s not, have you met him?’”

Even in a quiet room, Riley’s hands and feet continue tapping out a beat. The sturdy kitchen table actually vibrates as he lunches on chicken nuggets.

“Sometimes I’m like, ‘Shhhhh. Riley, you need to be quiet,’” says Arin Spindler. Ten seconds later the tapping starts again. “It’s constant,” Riley’s mother says. “There’s always a beat to music.”

Riley’s piano teacher, Lisa Falk, discovered another of Riley’s gifts. Play any note on the piano and Riley can name it. The third-grader possesses a trait, rare even among musicians. He has perfect pitch.

“He just doesn’t sit down and play a song like a recital for grade school students who don’t want to be there. He puts his emotion into it,” says Falk, who has worked with Riley for nearly two years – during which Riley has begun composing his own songs.

Still, asked what he wants to do when he grows up, Riley defaults to his favorite class at school. He wants to be a gym teacher.

As for his music, “it’s just something that he does that’s fun,” his mother says. “I don’t think he understands how much of a career and where it could go and what it can do yet.”

Arin Spindler reflects sometimes about how far Riley has come the past eight years. “I’m the lucky one, I get to be his mom,” she says. “Both my husband and I, we’re the lucky ones.”