RIVER FALLS, Wis. – The dairy herd built over 80 years was dismantled in minutes.

When the auctioneer’s call faded, the end had come for another small dairy farm.

As a reporter, I’ve covered this story before. But this time, it’s personal. This time it’s the third-generation family dairy on which I grew up.

“This is on its way out,” my brother Jay Huppert concedes as the last cow is sold. “I got one more generation out of it than it maybe should have been.”

The upper Midwest has been losing dairy farms at a rate once unimaginable. During the past 15 years, Wisconsin and Minnesota have seen the demise of roughly half their dairy farms.

Land of 10,000 Stories: Huppert Dairy

Now, as milk prices have entered the third year of a prolonged slump, the trend has accelerated. Combined, Minnesota and Wisconsin are losing dairy farms at the rate of 15 a week.

“I’ve got a neighbor down the road three miles this way that sold his cows last Friday,” Jay says, gesturing to his left. “A guy down the road this way is selling his cows next week - we’re selling ours - it’s just kind of the trend, all the small farms are just quitting and moving on to something else.”

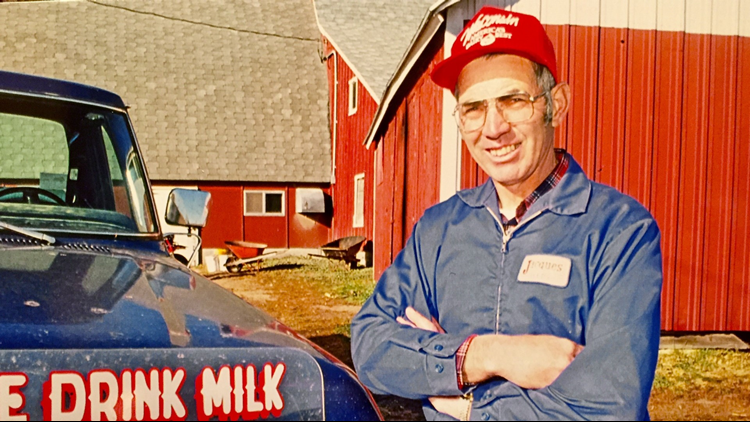

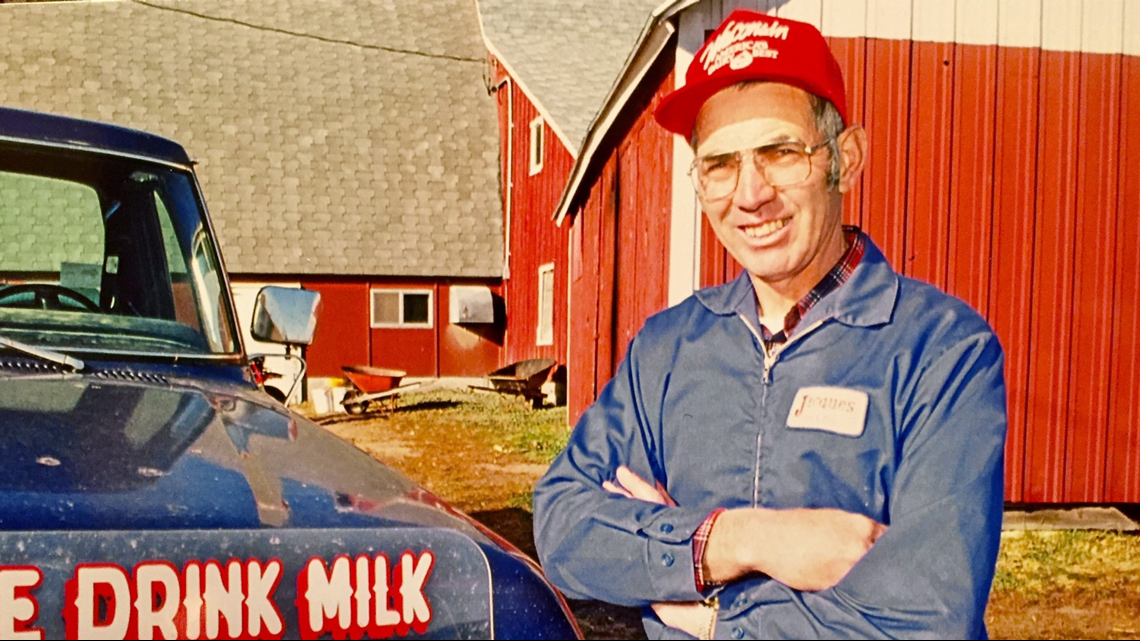

Jay is my younger brother by four years. He’s 52-years-old and more fit than many people in their 20s. Our grandparents, Clarence and Ethel Kusilek, purchased the family farm in 1938 and began building the herd.

In the early 1970s, our parents, Andy and Janet Huppert, took over the dairy and introduced my four siblings and me to the benefits of hard work and endless time spent together as a family.

But the dairy industry has changed. Today, technology has allowed for dairies with thousands of cows, increasingly milked by robots.

Sexed semen, artificially inseminated, allows dairymen to produce primarily heifer calves - the females that grow into milk cows. More heifers give dairymen the means to expand herds quickly should milk prices spike, but also results in more supply, which just as quickly can drive prices down.

Today, one 6000 cow herd can equal the production of a hundred small dairy farms like the one Jay and Lisa have been running.

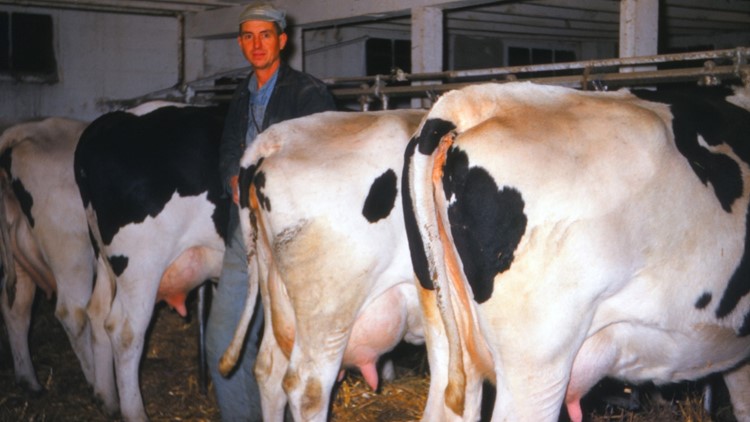

A few nights before the auction, Jay and Lisa milked their 60 cows together. Most cows are greeted by name. “Hi Sasha, hi sweetheart, how are you?” Lisa asks, as she hugs a Holstein around her neck.

Few of Jay and Lisa’s neighbors saw the sale coming. “It caught me by surprise,” says Dennis Kusilek, as he power-washes one of Jay’s John Deere tractors.

It’s Dennis’ third day volunteering his time to help his neighbors get ready for their auction.

“I thought Jay would be farming for 10 more years because he was so good at it, and he always seemed to love it,” Dennis says.

Both Jay and Lisa loved farming. They grew up on dairy farms within miles of each other and started dating in high school. Together, they were awarded the trophy seven years in a row presented to Pierce County’s top producing dairy herd. During those seven years, Jay never missed a milking. No vacations. No days off.

“He’s out the door at five in the morning,” Lisa says. “The earliest he comes back in is eight o’clock at night.”

Jay has never been one to complain about the work, but the grind of 15-hour days has become more difficult when there’s so little to show for his efforts financially.

Outside, Jay’s tractors are lined up for the sale. The newest among them is 27-years-old. Jay can’t begin to think about replacing old equipment when tractors have tripled in price, while the price of milk is stuck at 30 years ago.

“We can borrow all kinds of money, but you know someday they’re going to want it back,” Jay says.

In a strange way, their century-old barn and well-used tractors have become Jay and Lisa’s greatest assets. The couple can walk away from dairy farming, pay off their modest debts with the proceeds of their sale, and continue to own their farm. Other dairy farmers have found themselves too deep in debt to do the same.

Jay has taken a job at a factory. Lisa will continue to cut hair at her in-home salon. After making their decision to sell their herd, they rented their land to a crop farmer.

“Most of the neighbors are going to tell you Jay is one of the best dairymen around,” says Terry Kuhn, Jay’s feed dealer. “There’s a lot of dairy farmers out there, kind of taking notice, wondering, ‘If Jay is selling out, where does that leave me?’”

If their children had been interested in farming, Jay and Lisa might have tried to get bigger themselves. But how could they encourage their children to farm, with milk prices so unsettled?

So, both agreed, it was time to quit – a conclusion Jay reached first.

“The hardest thing he said to me was, he was afraid he was letting me down that he was quitting,” Lisa says, with her voice breaking. “And I don’t feel that way at all. I want him to feel good and be happy.”

Lisa says she’ll miss the animals and the time she and Jay spent together working. They’ve always made such a good team.

“Dairy let me down, the industry changed,” Jay says, acknowledging that technology and consolidation has brought change to other industries too. Hardware stores have closed too, when a Home Depot opens nearby. The similarities cannot be missed.

Jay’s auctioneer, Barry Hager, has completed two dozen dairy herd sales this spring. A former dairyman himself, Barry now conducts sales for others.

“Unfortunately, the prices today are to a point, even if you’re the best manager with zero debt, even on the best day, you’re breaking even,” the auctioneer says.

Barry can drive down most any rural road and count the empty barns where he’s conducted sales. “It’s sad to see that,” he says. “It’s an era that’s on the way out unfortunately – the small family farm."

Within a couple hours of the start of the sale, Jay and Lisa’s cows are loaded into trailers and shipped off to other dairies whose owners are still hoping for a turn-around.

There is sadness, but Jay and Lisa acknowledge it feels as if a weight has been lifted.

“It was fun, it was a great life, but I think there's better things out there.” Jay says.