MINNEAPOLIS — A rite of passage brings through the same door on a Saturday 88-year-old Willie Thurman for his 8th haircut of the year – and Quetay Collins, just turned 2, for the first barber shop cut of his life.

Willie, first in the chair each Saturday, joshed with the shops’ three barbers through most of his trim, while Quetay didn’t hide his tears.

“He's not happy right now,” his mother said, smiling, as she held up her phone to capture the moment on video.

This rite of passage has played out for generations in the black barbershops of North Minneapolis and beyond.

“No matter if it's Barack Obama or some kid that just got out of jail, they all have to come through the barber shop,” Houston White says, taking it in. “The barbershop is the black man's country club.”

Houston owns this club to which Willie and Quetay belong: HWMR (which once stood for Houston White Men's Room) a barber shop that's become much more.

“This is our place,” Houston says.

Houston's wheels are turning, even as he works his scissors. “I want to envision what we could do on this corner,” he tells a customer caped and seated in his barber chair.

Houston was 29 in 2008 when he purchased the building on the corner of 44th and Humboldt previously occupied by a coffee shop.

Yet, “It’s not about the building,” Houston insists. It’s about what’s taking place inside his barber shop.

On any given evening, Houston’s barber shop could be playing host to a concert, an art show, or any number of politicians or speakers.

A pinned-up photo shows a visit from Governor Tim Walz. In another, Houston is sharing a laugh with Minneapolis mayor Jacob Frey and police chief Medaria Arradondo.

It’s a place where two elementary school boys from the neighborhood – one a comic book writer, the other a bow tie designer – could set up a pop-up shop under Houston’s watchful eyes to sell their wares.

In the same space, 60 young black men gathered last month for a conversation with the CEO of Target.

Houston hopes someday that same CEO will bring a small format Target store to his corner.

“Could happen?” a reporter queries Houston.

“Will happen,” the barber responds without missing a beat.

Why wouldn’t he be confident? Houston’s line of clothing debuted nationwide last month in JCPenney stores.

“They sold out and they reached out, trying to re-up,” Houston says proudly.

Not bad for a guy who took a wrong turn at a young age.

“Got arrested in September, first semester, of my 9th grade year,” Houston says.

Houston was selling drugs just down the street from North High – his school. He insists the transactions had more to do with his love for “the hustle” than intent to commit a crime.

Whatever his motivation, Houston found himself in the back of a squad car.

“The handcuffs hurt. They didn't say, 'This kid’s 14, let's be light on him,'” Houston says.

"Going to juvenile detention and seeing my mom's reaction when she came to see me – yeah, it's just not a place you want to be.”

Having had enough of hustling drugs, Houston turned his ambition to cutting hair. “The intersection of hustling and art,” he calls it. Quick cash for a service performed - barbering fit him perfectly.

When his aunt let him set up a shop in her basement, young Houston had his path.

Today, he lights the way for other black boys trying to find their way too.

“Started working in 5th grade, now I'm in 8th,” 14-year-old Alfred Foster says as he spreads ice melt on the sidewalk in front of the barber shop.

Inside, 19-year-old Khalil Jones loads soda and water into the shop’s mini-fridge. Like Alfred, he’s been with Houston for three years too – paid for his weekend work in both money and mentoring.

“When you come here you feel the love,” Khalil says.

Khalil values the business skills Houston has taught him, as well as skills of the life variety, like tying a bow tie.

“He taught me that too,” Khalil says, smiling, a perfectly tied bow beneath his chin.

Alfred remembers walking into the shop silently, head down, early in his employment.

“He made me re-renter and say, ‘Good Morning,’ he said you always want to do that,” Alfred says.

The lesson stuck, just like Houston hoped it would.

“I believe that social intelligence is one of the most important things in life. The CEOs have high social intelligence,” Houston says. “It's decorum, like making people feel good around you.”

So, while Houston recently held a class in barbering for two neighborhood boys who asked, he also offers lessons in golf.

“Because golf is a game for power-brokers, it’s a game for life,” Houston explains. “The way to get a promotion is to play golf with your bosses, because you get time to interact with them on a personal level.”

Houston pulls up on his laptop a picture of another neighborhood boy. He is well dressed and leaning proudly on a golf club surrounded by a sea of lush green.

Houston can’t get enough of the photo. “It embodies kind of who we are as a people,” he says, “confident and prideful and beautiful.”

Houston has known setbacks. He lost a home-building venture to the great recession. In November of 2018, he also lost his wife Donise to cancer.

Yet, optimism stirs inside him. Houston can’t help but see a brighter future for North Minneapolis, with his shop as a catalyst.

“I refuse to accept anything that's not excellent,” he says firmly.

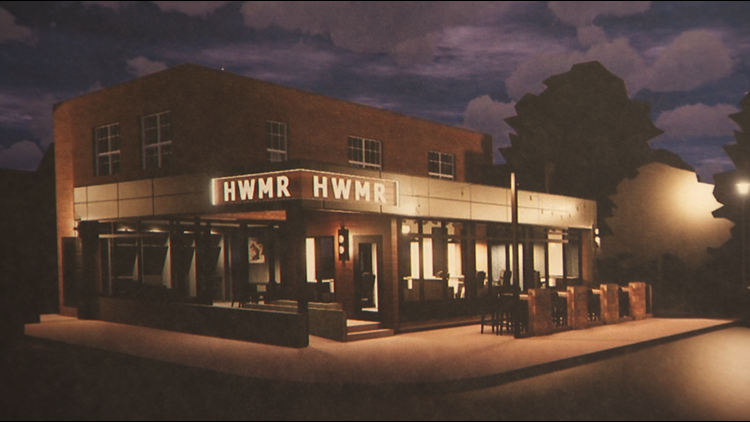

So, the plans are already drawn and hanging on his wall for a refurbished barber shop with retail space for his clothing line and a patio cafe for sipping craft beer, wine and spirits.

“Our Country Club,” Houston has written in bold letters beneath the architect’s renderings.

He’s confident he could succeed in the suburbs. But why would he want to?

“There’s something about the inner city, it’s just rich, it’s different,” he says.

Besides, “It’s so much more special when you take a place that has meaning to you and make it amazing,” Houston says.