ST. PAUL, Minn. - If you've counted yourself at any point among the children fascinated by the dinosaurs at the Science Museum of Minnesota this would be a good time to acknowledge some prehistoric passion.

No bones without it.

On Tuesday, Science Museum staff and volunteers will hold a retirement party for Bruce Erickson – the man who brought dinosaurs to Minnesota.

“We have this wonderful collection built by a single individual,” says Ed Fleming, the museum’s curator of archeology. “He’s responsible for the paleontology program at the science museum.”

The Science Museum of Minnesota had a handful of bones, but no dinosaurs, when in 1959 it hired a Minnesota-born paleontologist – then engaged in what Erickson describes as “grunt work” in a lab at the Field Museum in Chicago.

Erickson was hired on one condition. “I had to promise that I'd collect a dinosaur for the museum,” he smiles.

Two years later, working in Montana’s Hell Creek Formation, Erickson delivered, when he and his team unearthed the bones of a triceratops.

To this day Erickson’s discovery is one of only four real triceratops on display in the world – and the largest of them, according to the Science Museum.

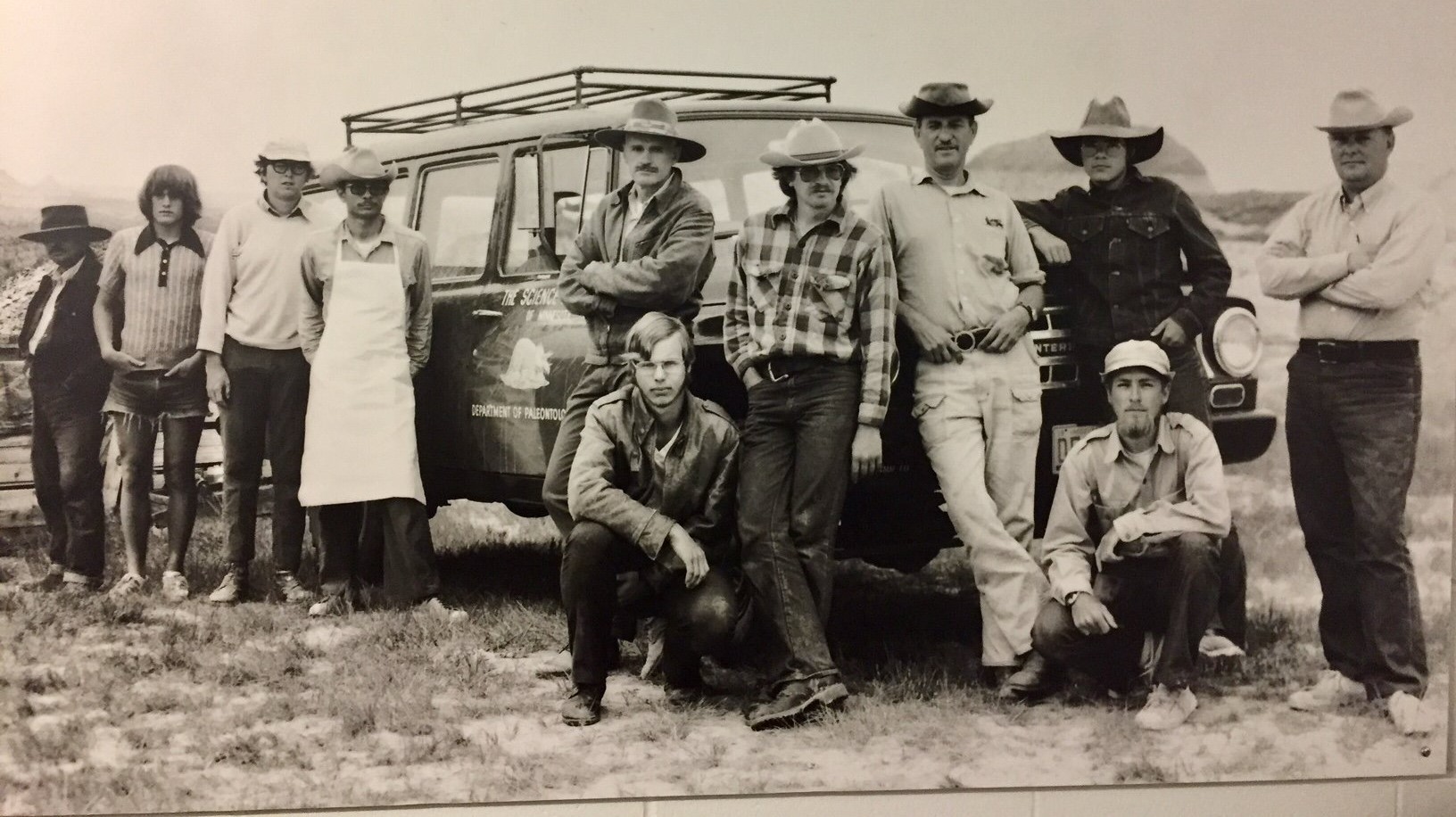

But Erickson was just getting started. Over several decades, Erickson assembled teams for expeditions in North Dakota, Montana and Utah. In their most extensive work, Erickson and his crew spent 27 seasons unearthing crocodiles and other fossils at the Wannagan Creek Quarry in western North Dakota.

The work was often grueling, but productive, as the expeditions produced hundreds of thousands of specimens now contained in the museum’s displays and research vault.

In a reference to the tents his crews slept in, Erickson says, “I spent probably a third of my life under canvas - in the army and then in the field.”

The volunteers in the museum's paleontology lab speak of Erickson in terms normally reserved for childhood sports heroes.

“I've followed Bruce’s career since I was a kid,” says Mark Ryan, who grew up in Duluth reading about Erickson’s expeditions.

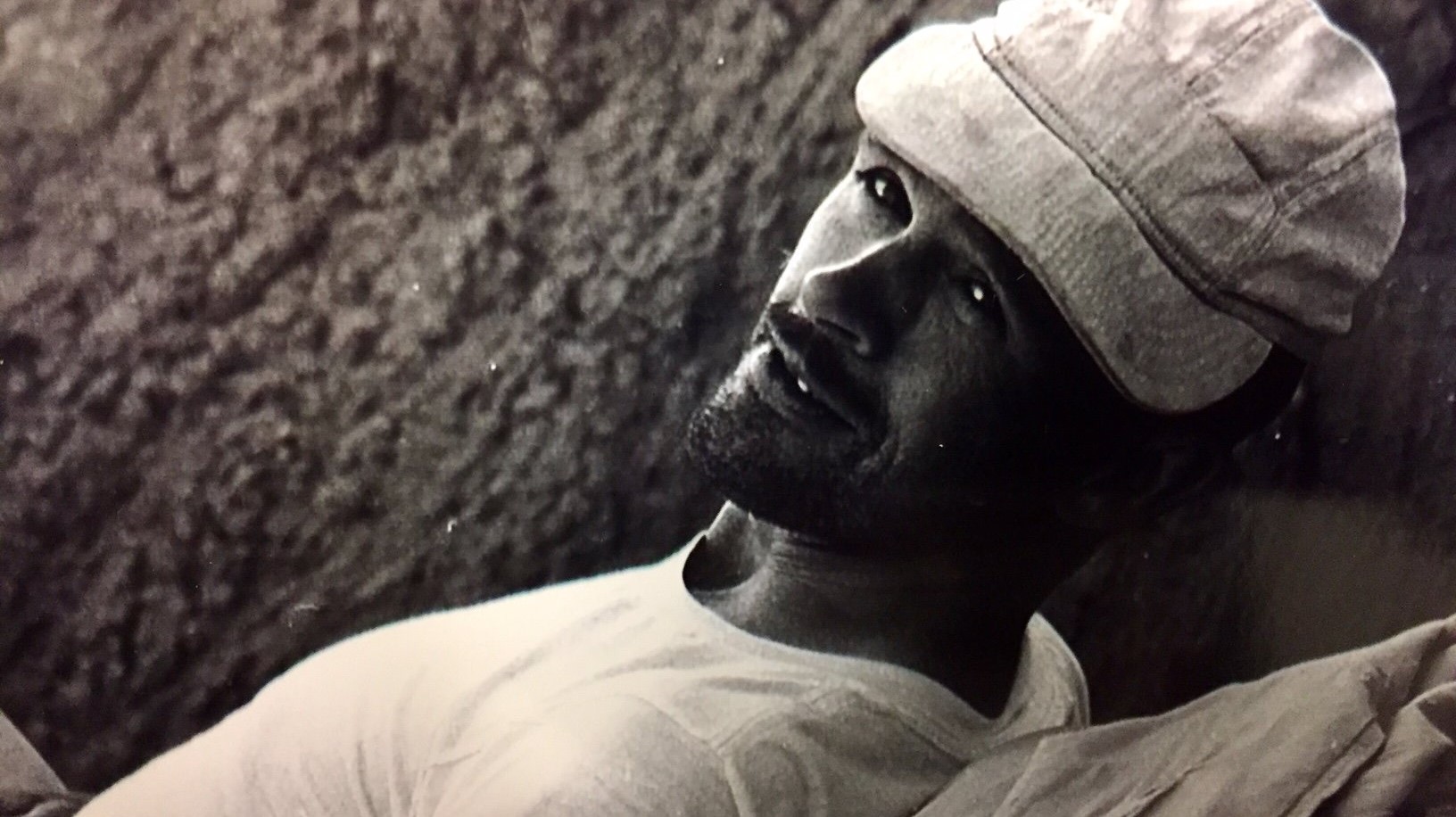

Pictures of Erickson from his early expeditions present a dashing “Indiana Jones” figure. “He's the one with the broad-brimmed hat,” says volunteer Neva Key. “He was a striking figure.”

The dusty old boots that Erickson wore on the exhibitions now sit in a display case outside the museum’s paleontology lab.

He may have retired his boots, but Erickson kept coming to work – 20 years after he might have retired – under his official title: Philip W. Fitzpatrick Chair of Paleontology.

“The pursuit of knowledge, I think, drives him,” says Fleming.

Erickson acknowledges he could have called it quits sooner, “but there's so much to do here, that's why I stayed.”

Indeed, even after Erickson retires at the end of July, he plans to continue to come to the museum as the paleontology lab’s only volunteer with an emeritus title.

Bruce Erickson kept going for 58 science museum years. And still he'll be searching for what lies ahead around the next bend.