BURNSVILLE, Minn. – At Gideon Pond Elementary, the morning greeting is delivered by the principal.

“Make a positive choice,” Chris Bellmont counsels his students over the school public address system.

The principal may deliver the message, but a 23-year-old teachers’ aide makes it stick.

“He is the glue,” agrees Bellmont.

On any given morning, Hudayfi Barsug can be found darting from classroom to classroom. He’ll eventually visit them all – dancing with kindergartners, getting a smile from a second-grader he helps with a math problem, and addressing the latest educational crisis: a student who dressed himself a little too quickly.

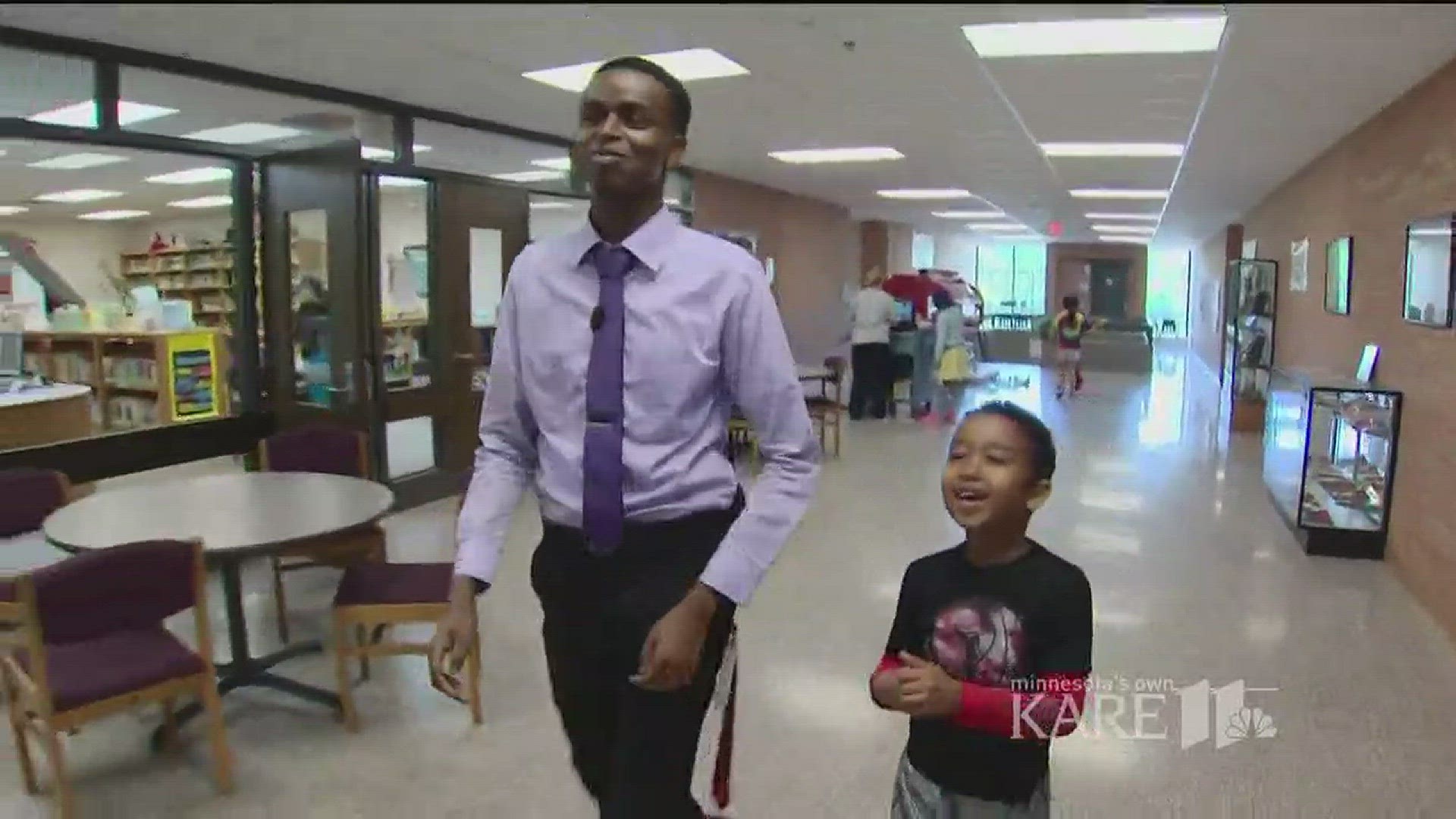

“He forgot his socks, so he's going to get more socks from the nurse today,” says Barsug while spiriting the happy student down the school hallway in search of proper footwear.

Though Barsug is 23, he could easily pass for 18. He is also Somali, which places him in a unique position to connect with an increasing number of students at Gideon Pond.

“My role is being here for the kids,” he says.

More than 40 percent of Gideon Pond’s students are now Somali – while zero percent of the teachers are.

“I'm yet to interview a candidate,” says Principal Bellmont, who has been able to hire four Somali support staff members, but no teachers.

It’s not for lack of desire. “I would love to,” Bellmont says, but none can be found.

Bellmont has been trying since arriving two years ago from his job as an assistant principal at Burnsville High School, where he took a liking to the teenage version of Barsug – a wide-smiling teachers’ favorite who helped found the school’s Muslim student association.

“I remember being really impressed with Hudayfi's leadership even at 16, 17 and 18 years old,” Bellmont says.

Barsug graduated, took some community college courses and was working as a night manager at Kmart when he found himself summoned to Gideon Pond.

“We had an opening for an educational assistant,” Bellmont says. “A 15-minute interview was all it took to be reminded of the kind of kid I knew five years before.”

Shortly before his principal spoke about him, that same “kid” had tucked himself into a nook with a young Somali student and a book. Helping children with their reading is among Barsug’s responsibilities.

It's easy to understanding why Barsug feels a connection to new immigrants, having arrived in the Twin Cities himself at the age of 11 – scared and speaking not a word of English.

It's also telling that Barsug takes his role as disciplinarian so seriously.

“I'm worrying about today, you were not listening,” he softly tells a boy who was asked to leave gym class after misbehaving. They stand in the hall, Barsug’s lean frame bending over while the boy looks down at the floor.

Later, Barsug says, “I don’t like being the bad guy, I like being the solution guy. I don’t want them blocking their education.”

Among Barsug’s acquaintances at Burnsville High School were some of the young Somali men convicted of the plot to join the terrorist organization ISIS.

“Two or three kids were from my class. Reading about it, it was just memories come back of the good choices I made,” he says.

They are choices Barsug attributes in part to his mentors at Burnsville High School – the kind of mentor he’s trying to become.

“I think Hudayfi is like a brother to me,” wrote fifth-grader Jabril Osman in a recent essay. “Hudayfi is a working man and he's my role model.”

Barsug wraps up his conversation with the boy from gym class. “Be respectful, that's it, OK?” he asks the student. “C’mon, can I see some smile?” The young Somali boy nods in affirmation.

“I know many of the kids that he works with might be from the Somali culture, but I know every kid in the school looks up to him,” says fifth-grade teacher Tom Robison.

Principal Bellmont agrees.

“What you're seeing is authenticity,” he says. “It’s limitless, the effect he can have on the rest of the world.”

Already, Hudayfi has affected his principal.

The principal and the teachers’ aid regularly pair up to visit Chancellor Manor, the Burnsville apartment complex that is home to a majority of the school's Somali families. For years it was Barsug’s home, too.

Now Barsug and Bellmont visit parents and drop off free books for the children. Far cry from Bellmont’s first visit to Chancellor Manor alone, dressed smartly in a sport coat and tie - and mistaken by parents for an FBI agent.

Barsug now bridges the gaps with introductions and language translation, helping Bellmont to feel at home at Chancellor Manor, too.

“I don't know what he cannot do, I'm not sure, I'm truly not sure,” says Bellmont of Barsug.

Oh, and that struggle to find the school's first Somali teacher? Barsug might just have that covered, too.

“I want to be a teacher, in elementary,” Barsug has decided.

Bellmont couldn’t be happier with Barsug’s decision, but offers a gentle warning to other school districts. “I have dibs on Hudayfi,” he smiles. “We want him back in this school.”

Barsug is now looking into colleges. Yet, the soon-to-be student is already teaching.