PEMBINA COUNTY, N.D. — In the remote area where North Dakota, Minnesota and Canada intersect, the miles upon miles of rural farmland can sometimes blend together.

Outside of the official international border crossing at Pembina, North Dakota, there are few markers to differentiate the lines between Canada and the United States. There's also very little — if any — signage to indicate which country you're standing in at any given moment.

It is here, near the small communities of Pembina and nearby Noyes, Minnesota, where U.S. Border Patrol agents have noticed a significant increase in irregular border crossings from migrants desperate to enter the U.S.

According to the most recent six-month data period in Fiscal Year 2023, the Border Patrol Grand Forks Sector reported 100 encounters with migrants from October 2022 through March 2023 — a figure that already surpasses the entire total from the previous fiscal year. Seventy percent of the people apprehended have been natives of Mexico, who can fly to Canada without a visa and then make a crossing attempt into the U.S.

Last month, in fact, Border Patrol agents rescued several men from Mexico crossing into northern Minnesota near Warroad, where they became stuck in frozen floodwaters.

"This year, we are probably going to see two and a half times the amount of apprehensions, if we keep on this pace, than we did all of last year. It's a significant increase," said Xavier Ruiz, the patrol agent in charge for the Pembina station. "We do have some indicators that the number could spike even further than that."

Although the numbers pale in comparison to the thousands of migrants attempting to cross out East, into states like New York and Vermont, the trends in the more remote border areas of the Upper Midwest point to a complex shift in the immigration crisis.

With COVID-era rules under the Trump and Biden administrations placing heavy restrictions on the number of people seeking "asylum" status at the southern border, more migrants are attempting to fly into Canada first in order to reach the U.S. via northern states. In many cases — such as the one that tragically killed a family of four from western India in January 2022 — human smugglers are involved in facilitating crossings into Minnesota and North Dakota.

"What we think is happening, is a lot of the alien smuggling organizations are actually building up their infrastructure on the Canadian side," Ruiz said. "They entice them with being able to cross the border easily, coming into the U.S., getting them jobs, but you know on the flip side, the harsh reality sets in. Once they cross they have to pay all that money back and they have to work under harsh conditions. It's false promises being made."

The surge in migrants at the northern border shows just how desperate many people have become to escape their home countries.

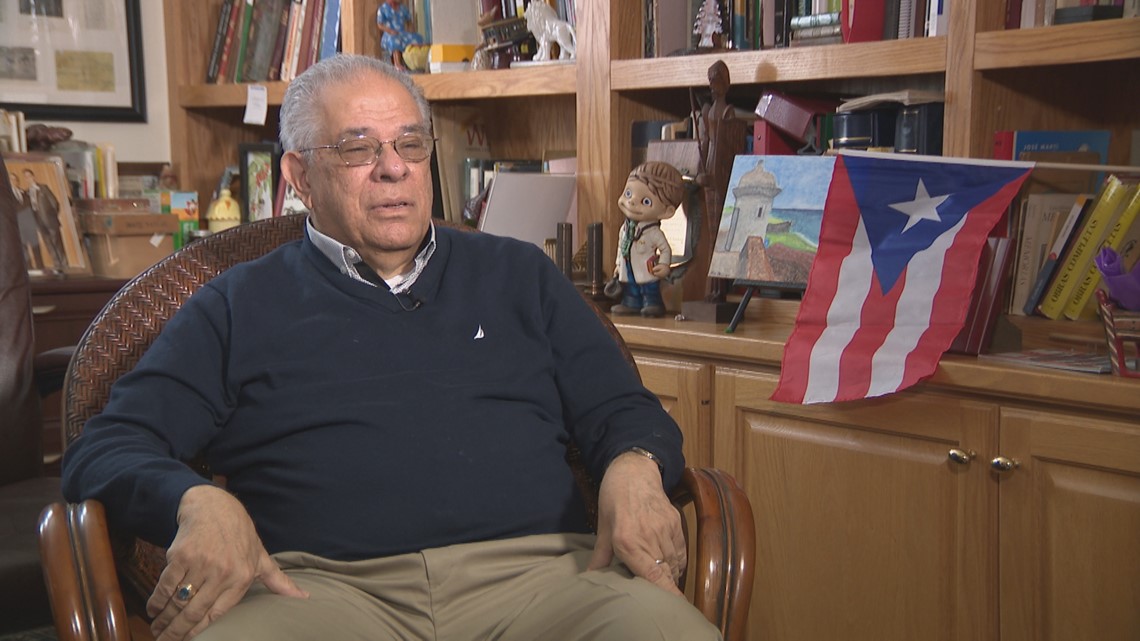

Dr. Miguel Fiol, a University of Minnesota neurologist, coordinates a community group that works directly with migrant families, particularly those from Latin America.

"What we know is a lot of the people who are asylum seekers are running away from persecution, or drug cartels, or poverty," Fiol said. "What I see in the patients that I care for, what we see in our community clinics, are just regular families looking for a better life who have extreme poverty and just have no way out."

Fiol has taken several humanitarian trips to the southern border. Although many of the migrants' stories in the south have been well-documented, less attention has been paid to the situation developing on the northern border.

Fiol said that families who've made the journey over the Canadian border into the U.S. are reluctant and fearful to speak publicly about their experiences.

"We have not had a lot of families come up and say, 'I crossed at International Falls,' or 'I crossed in Northern Minnesota.' They're just not talking about it," Fiol said. "But we know there have been attempts that have ended in fatalities."

Adding a twist to this complex story is the fact that the U.S. and Canada agreed to new asylum rules this spring, which restricts who can seek the status and where.

Under the Safe Third Country Agreement that dates back nearly two decades, the U.S. and Canada have been able to turn away asylum-seekers at official entry ports (for example, if an individual from Latin America first came to Canada, and then tried to gain entry into the U.S. at an official port, the U.S. could send that person back to Canada to seek asylum). However, the new agreement between the Biden and Trudeau administrations will apply the policy to the entire border, meaning someone apprehended outside of the regular port of entry can be sent back, too.

Separately, once the pandemic-era Title 42 policies expire late Thursday evening, new asylum restrictions from the Biden administration will officially take effect. Those rules, finalized this week, will "further incentivize individuals to use lawful, safe, and orderly pathways to enter the United States," according to Homeland Security.

Broadly speaking, the new policies will require migrants to either apply online to make a scheduled asylum claim at an official port of entry, or they will be required to seek asylum in the previous country they traveled through before reaching the U.S.

Dr. Fiol is part of the coalition that opposed the new policies, along with Ana Pottratz Acosta, an immigration law expert and associate processor at Mitchell Hamline School of Law.

"It's going to continue to drive people to go via more dangerous routes to come into the U.S. to reach safety," Pottratz Acosta said. "It's troubling because in many respects, we have really not guaranteed the right to apply for asylum in the way we did traditionally."

At the U.S.-Canada border, Agent Ruiz — who previously spent time working in Honduras and on the southern border — said he expects irregular border crossings to increase further in the coming months.

"I can tell you from my time down in Central America, a lot of it has to do with economics, lack of opportunity, lack of education and lack of jobs. Promises of a better life here," Ruiz said. "A lot of migrants come here with the specific purpose of working here, getting paid and then sending that money back to their country. It's a vicious cycle."

Watch more local news:

Watch the latest local news from the Twin Cities and across Minnesota in our YouTube playlist: