Native American Boarding Schools: A Lost History

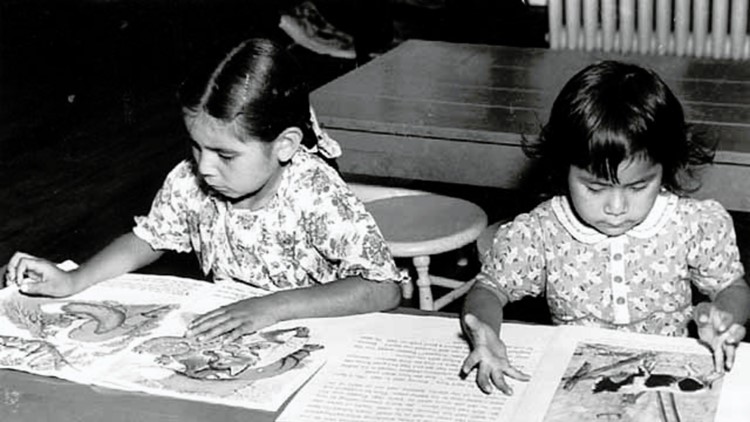

For decades, many American Indian children were forced to attend government-funded boarding schools designed to sever Native cultures, languages and traditions.

America's Indian schools

At the University of Minnesota, Morris, professor Gabriel Desrosiers teaches 20 students Anishinaabemowin – the language of the Ojibwe people.

It does not escape him that 120 years ago, on the very soil he stands on, speaking this language was forbidden and punished.

“Cultural genocide,” said Desrosiers. “One of the main goals was to assimilate and exterminate the Indian within.”

He's talking about an era of Indian boarding schools. Desrosiers’s mother and uncles attended them in their youth, schools that he says created childhood trauma and a broken family structure later in life.

“She didn't really know how to express or love,” Desrosiers said about his mother. “That all came from what she experienced as a child. All her brothers became alcoholics. They died alcoholics. Tragic deaths.”

After 215 children's bodies were discovered in a mass grave at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in Canada last summer, a reckoning with America's boarding school past awoke.

For 100 years, dating back to the 1860s, Native American boarding schools existed in the United States, and by historical accounts, the schools were funded by the federal government and meant to sever American Indian culture and “civilize the Indian."

Christine Diindiisi McCleave, CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition based in Minneapolis, had two generations of relatives that survived boarding schools. She explains how President Ulysses Grant gave federal money to churches at first to start these schools.

“He figured they would not be corrupt with those funds,” said Diindiisi McCleave. “So that is what opened the door to federally funded, church-run Indian boarding schools.”

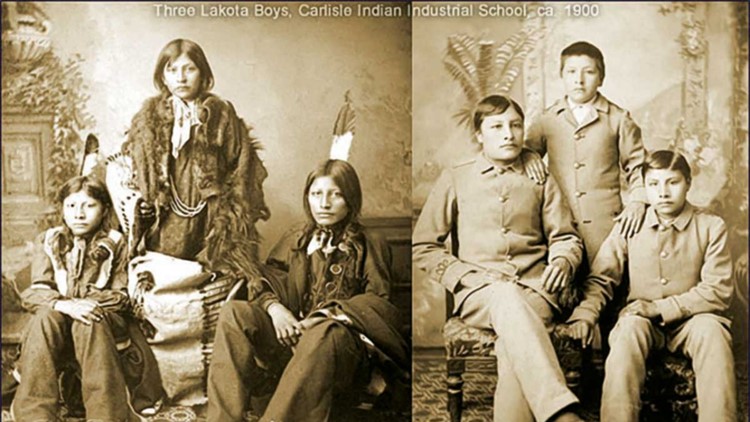

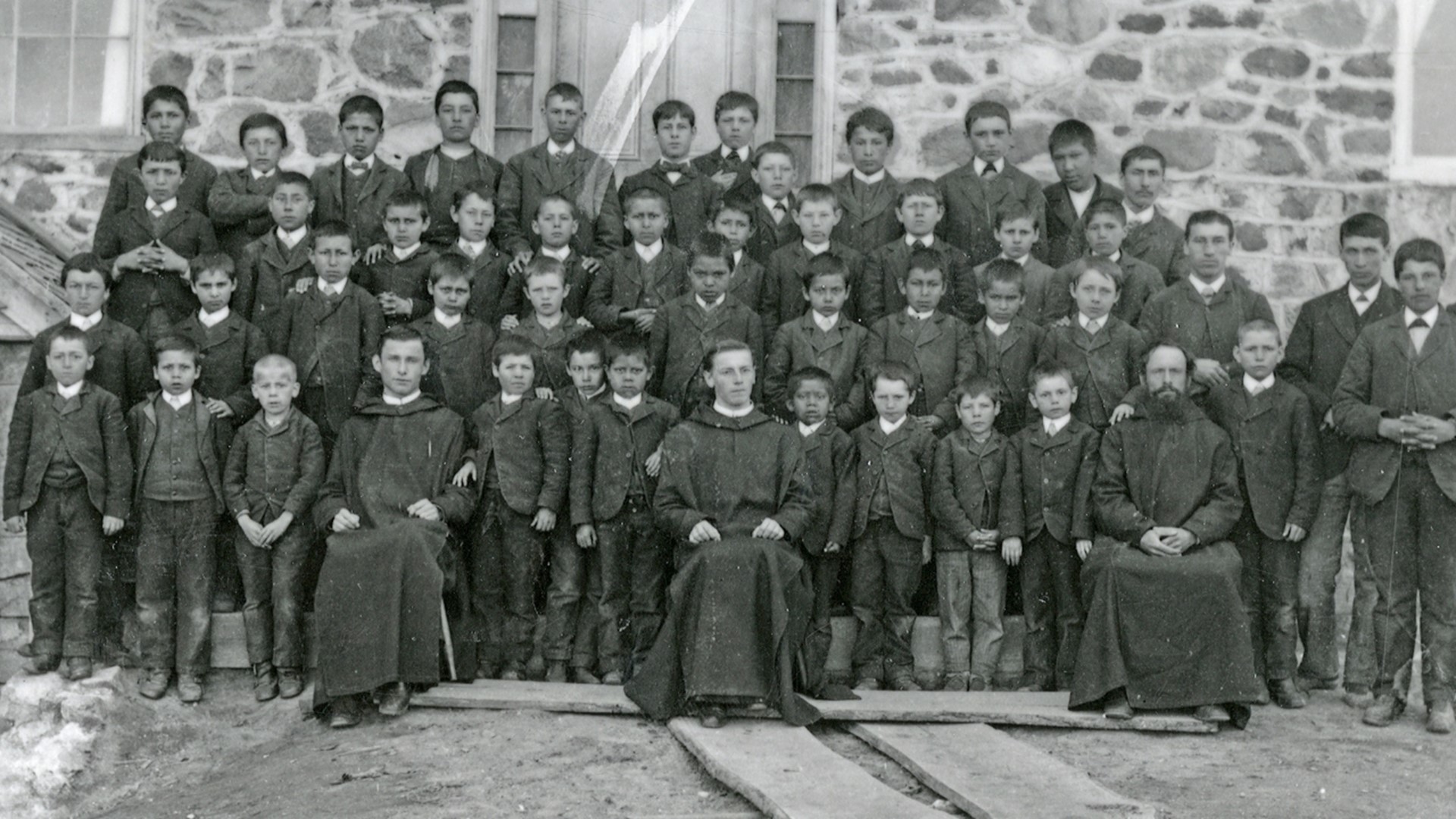

In 1879, U.S. Army Captain Richard Henry Pratt established the first federally funded, off-reservation Indian school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania that enrolled more than 10,000 American Indian and Alaskan Native children from more than 140 tribes.

Pratt famously once said in a speech, "They must get into the swim of American citizenship... Kill the Indian in him, and save the man."

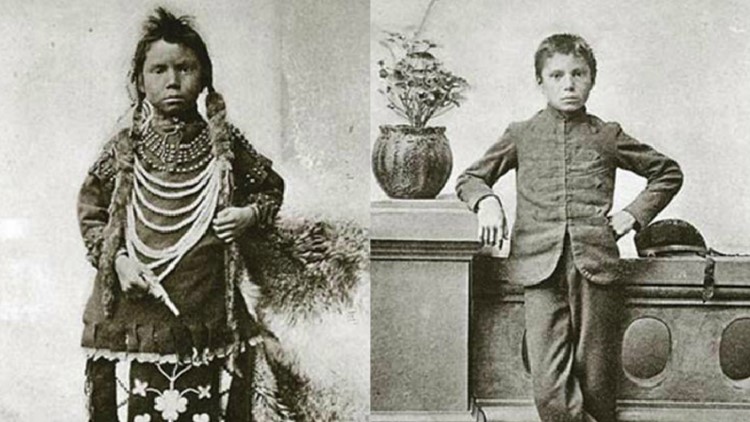

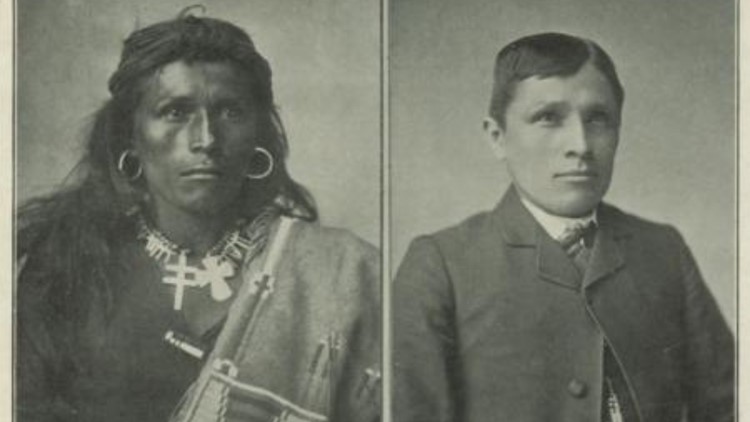

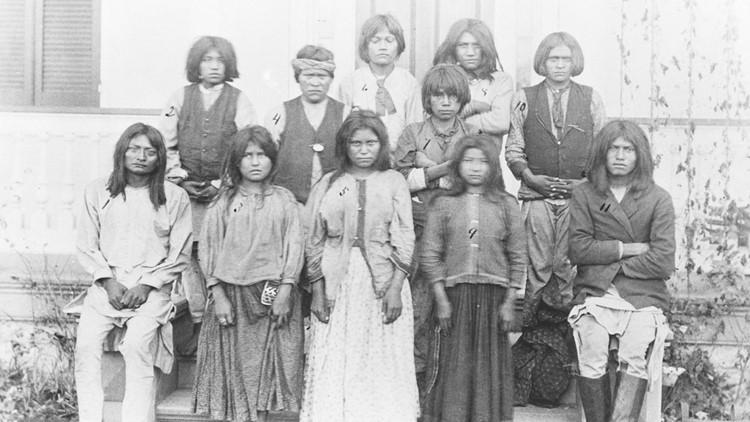

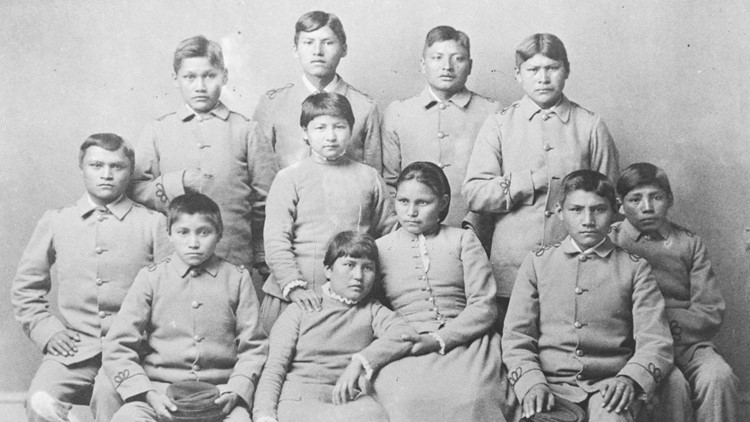

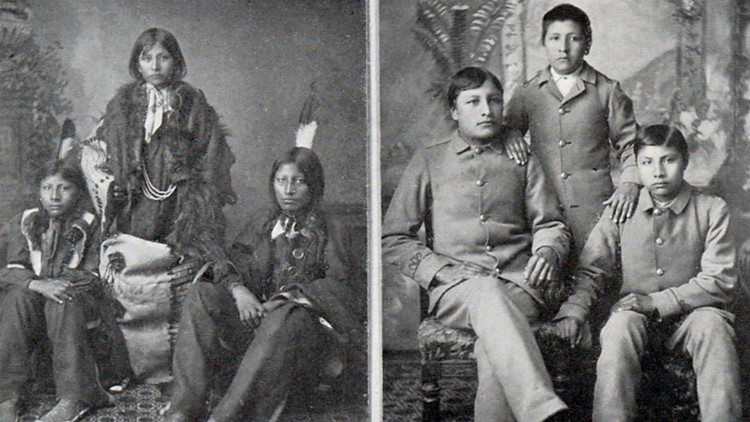

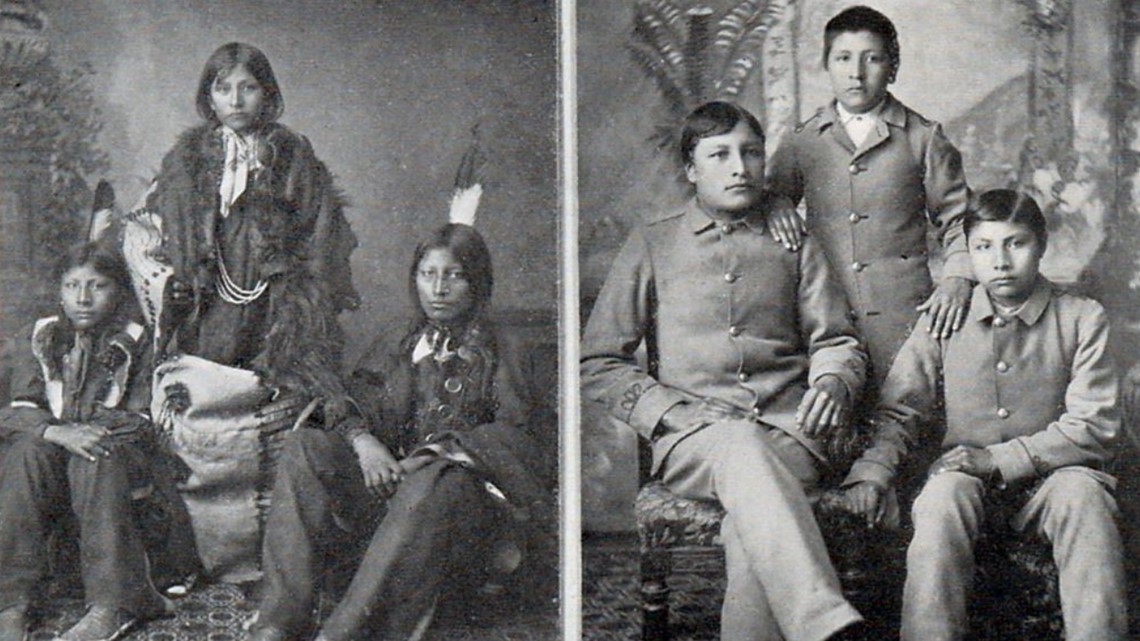

He also created propaganda for the cause, taking before and after photos of Native American students showing their Americanized appearance.

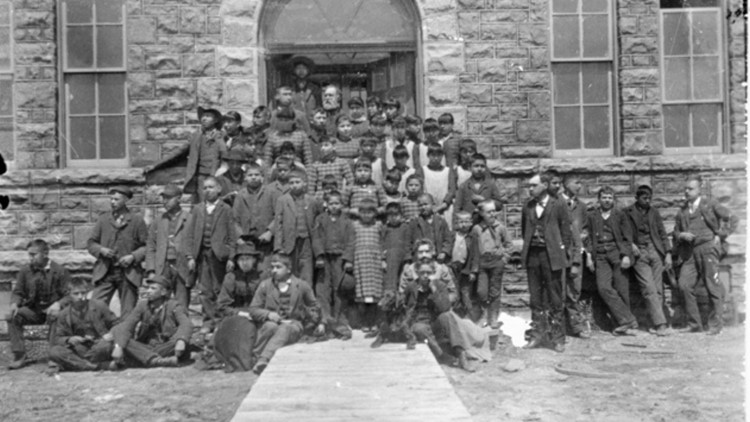

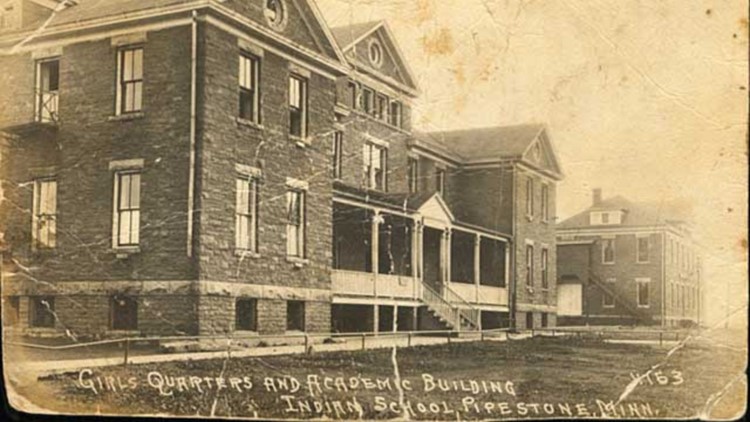

That school became a model for 367 such schools in the U.S., including 16 schools in the state of Minnesota, from Pipestone to Morris to Vermilion, according to the Healing Coalition.

No one, not even the federal government, knows exactly how many schools there were, nor exactly how many children attended them. There is no official record.

But according to the book “Education for Extinction,” an estimated 83% of Indian school-age children attended boarding schools by 1926 – hundreds of thousands of American Indian children.

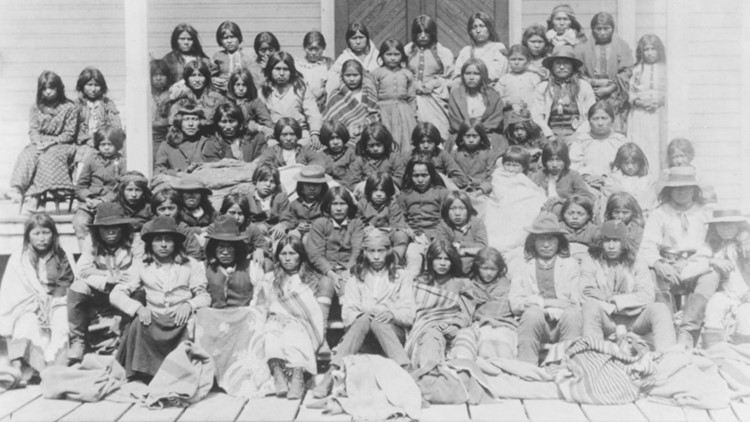

Laws were passed by Congress mandating Native American children attend boarding schools. Parents were threatened with jail or having rations and clothing withheld if they prevented their children from attending.

Conditions were often brutal.

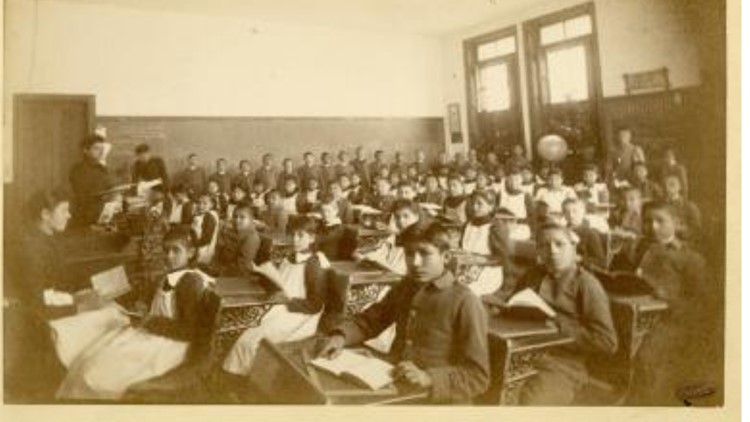

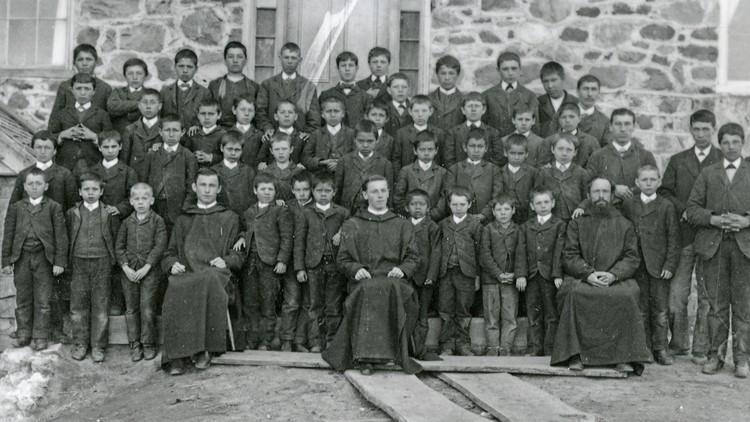

“They were run in a very militaristic style. They were given uniforms and given a number and referred to by number only. And their hair was cut. For many tribes across Turtle Island (North America) represents either grief or shame,” said Diindiisi McCleave.

“It depends on the era and it depends on the schools,” said Dr. Kate Beane, an American Indian Studies professor at the University of Minnesota and director of Native American Initiatives at the Minnesota Historical Society.

She calls the boarding school era one of “ethnic cleansing,” but points out not every school was that harsh. For some it was a matter of food security during poor economic times.

“My grandmother went to the Flandreau Indian School in South Dakota, and she had a wonderful experience there learning how to farm and sow, and her experience there as a student was starkly different than my grandfather's at a different school in South Dakota,” said Beane.

Each story is different. But the atrocities shared by so many are no longer going unnoticed.

“I distinctly recall [my mother] saying to me directly, 'If I don't put you in the boarding school, they are going to take you away from me,’” said Mitch Walking Elk during the Boarding School Survivor and Victim Memorial March and Rally in Minneapolis.

A march is a voice, but a secretary in the federal government? That’s power.

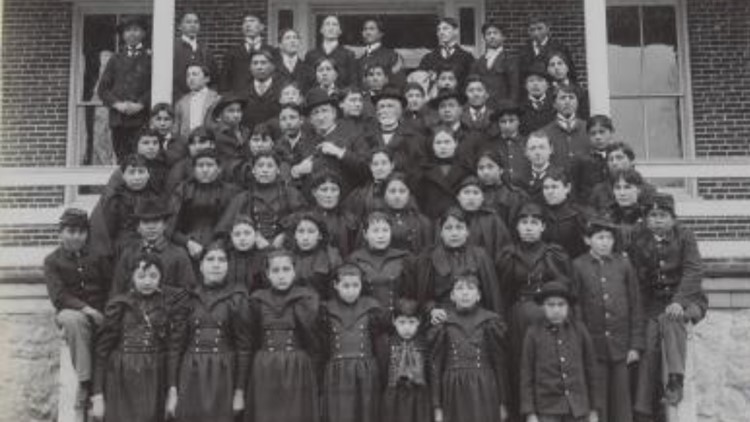

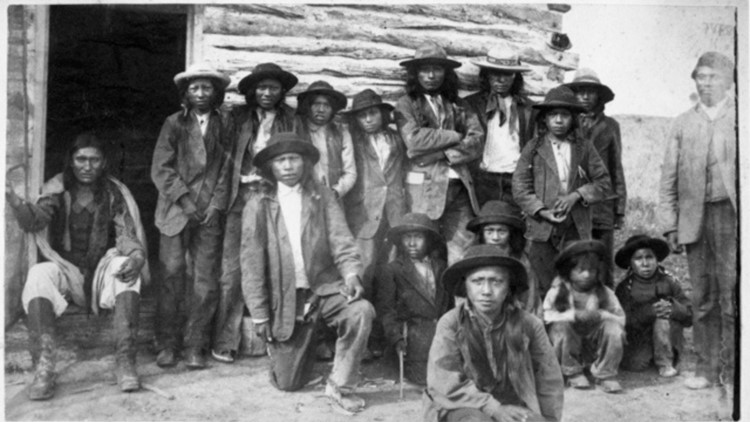

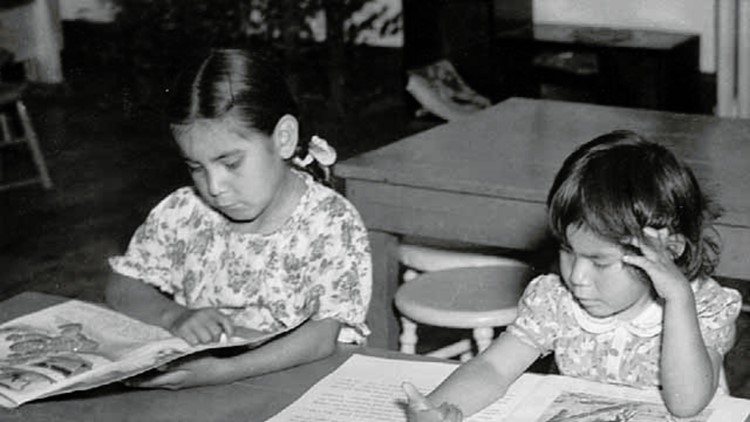

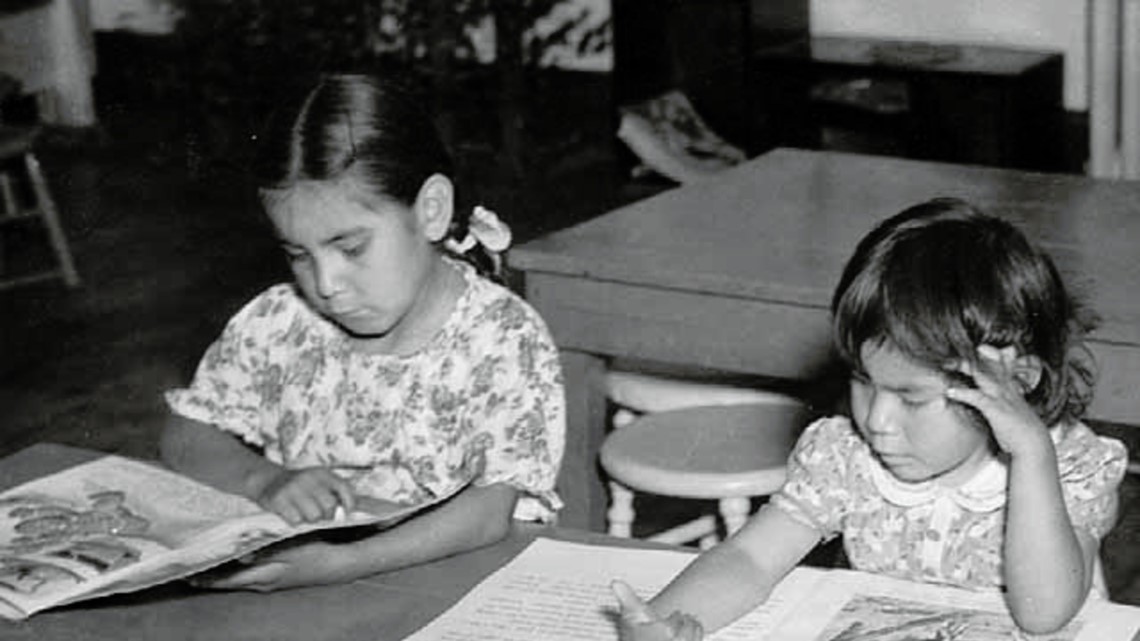

ARCHIVES: The faces of Native American boarding schools

"We must shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be," said Deb Haaland, Secretary of the Interior Department, during a speech last summer.

The former Congresswoman and first Native American Interior Secretary announced, for the first time in the U.S., the federal government will investigate records, stories, archives, and eventually use ground penetrating radar to find out how many children attended these schools and how many never made it home.

The report is scheduled to be finalized and given to Sec. Haaland on April 1, 2022.

Many say it’s time for the story to be told from the perspective of the American Indian.

“Acknowledgement is the very first step,” said Beane. “Acknowledging that this history happened. Recognizing that this history happened. Recognizing the impact on this history is the next step.”

The lost graves at Morris

In the heart of the University of Minnesota, Morris campus, a stone sculpture overlooks the student traffic.

An Anishinaabe grandmother, carved out of limestone, appears warm and resilient. A grandson, dressed in a boarding school uniform, looks sad as he leans his head on the grandma. A granddaughter hides her face, clutching her grandma, resisting what's to come.

It's a daily reminder of this property's painful past as a Native American boarding school.

“If you ask any Native American, ‘Did children die while at boarding schools?’ They've known for years that the answer was of course,” said Janet Schrunk Ericksen, acting chancellor at the University of Minnesota, Morris. “It's only a discovery to people who haven't thought about it before.”

Schrunk Ericksen, who entered the chancellor role in June, is now trying to manage the reckoning of this site's history and the potential that children's remains are buried somewhere on or near campus.

“The problem is there really are not good records. We don't have detailed — certainly not objective — accounts of what happened at the time, nor do we have accounts from the individuals who were at the schools,” said Schrunk Ericksen.

In 1887, some 70 years before Morris became a state university, Sister Mary Joseph, a Catholic nun, started the Morris Indian Industrial School with funding from the government.

She recruited Native children from reservations in South Dakota and North Dakota and later across Minnesota, according to a report from historian and UMM professor Wilbert Ahern.

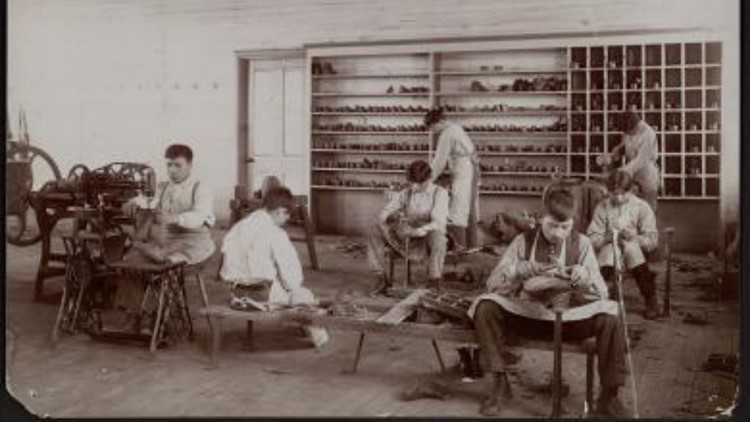

Children received uniforms and haircuts. Only English could be spoken. Half the time was spent in the classroom and half was spent learning agriculture and domestic work that partially funded the school.

Ahern writes, "the curriculum emphasized the value of the white man's way and at least implicitly the evil of the child's home."

Gabriel Desrosiers is a Morris alumni and now a professor of Anishinaabe language, song and dance.

“One of the main goals was to assimilate and exterminate the Indian within,” said Desrosiers. “The children were a target, because they are the ones who will keep traditions alive. So, they targeted the children using education as a method of doing this.”

ARCHIVES: Native American students at Minnesota's boarding schools

The second chapter of the school appears much worse. The federal government purchased and operated the school in 1896. Records show parents were lied to, according to Ahern. Some children weren't allowed home for summer break, creating distrust among Native families.

A typhoid outbreak killed one student and sickened 37 others.

There were scandals and sexual improprieties between staff and students.

Superintendent William Johnson was accused of raping two students and having an affair with a staff member.

This all led to the school's closing in 1908. The property was given to the State of Minnesota under the condition that all future Indian students be admitted "...free of charge for tuition and on terms of equality with white pupils."

Today, one building remains of the original industrial school. Once a dormitory for students, it’s now a research center for students from underrepresented communities.

“I think that history makes me feel like there's a lot of work to be done,” said Dylan Young, a junior from the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Indian Reservation and the vice president of the Morris student body.

The university says research from 2018 indicates anywhere from two to seven children died at the school with no record of being returned home to their families, meaning the children could potentially have been buried on or near campus.

Dylan helped pen a petition urging the university to search for the graves. The petition now has more than 30,000 signatures.

“This is a college campus. This is a living learning community. How can we expect students, especially indigenous students, to be able to completely focus on education and have a clear mind and focus solely on their studies if their relatives are buried beneath where they are supposed to be going to class?” said Young.

We asked Schrunk Ericksen if she is willing to begin searching for these potential graves.

“I'm completely willing to do it. But I think the question isn't if I am willing to do it. The question is, is this what our tribal nations want us to do?” said Schrunk Ericksen.

She says there is no record indicating where children might have been buried.

“None of those maps reference a cemetery, which makes it enormously challenging, and the ground has been significantly disturbed over time. It's a big challenge, and again, we will move ahead and I think we have the right partners to move ahead. People who know way more about it than I do. And they will help us do the right thing,” she said.

Young says he harbors a personal responsibility to ensure any remains are found and returned home to their families.

“I think all of us should,” said Young.