MINNEAPOLIS - In the past three years, mechanical engineers at the University of Minnesota have developed custom 3D printers that can create artificial skin, print electronics onto skin, and recreate functional organs.

Now, associate professor Michael McAlpine has his sights set on something even bigger.

"My mom is blind in one eye," McAlpine said. "She said, 'When are you going to print me a bionic eye?"

It's question McAlpine and his team are close to answering.

"It's not science fiction," said research associate, Sung Hyun Park. "It's real, it will be real."

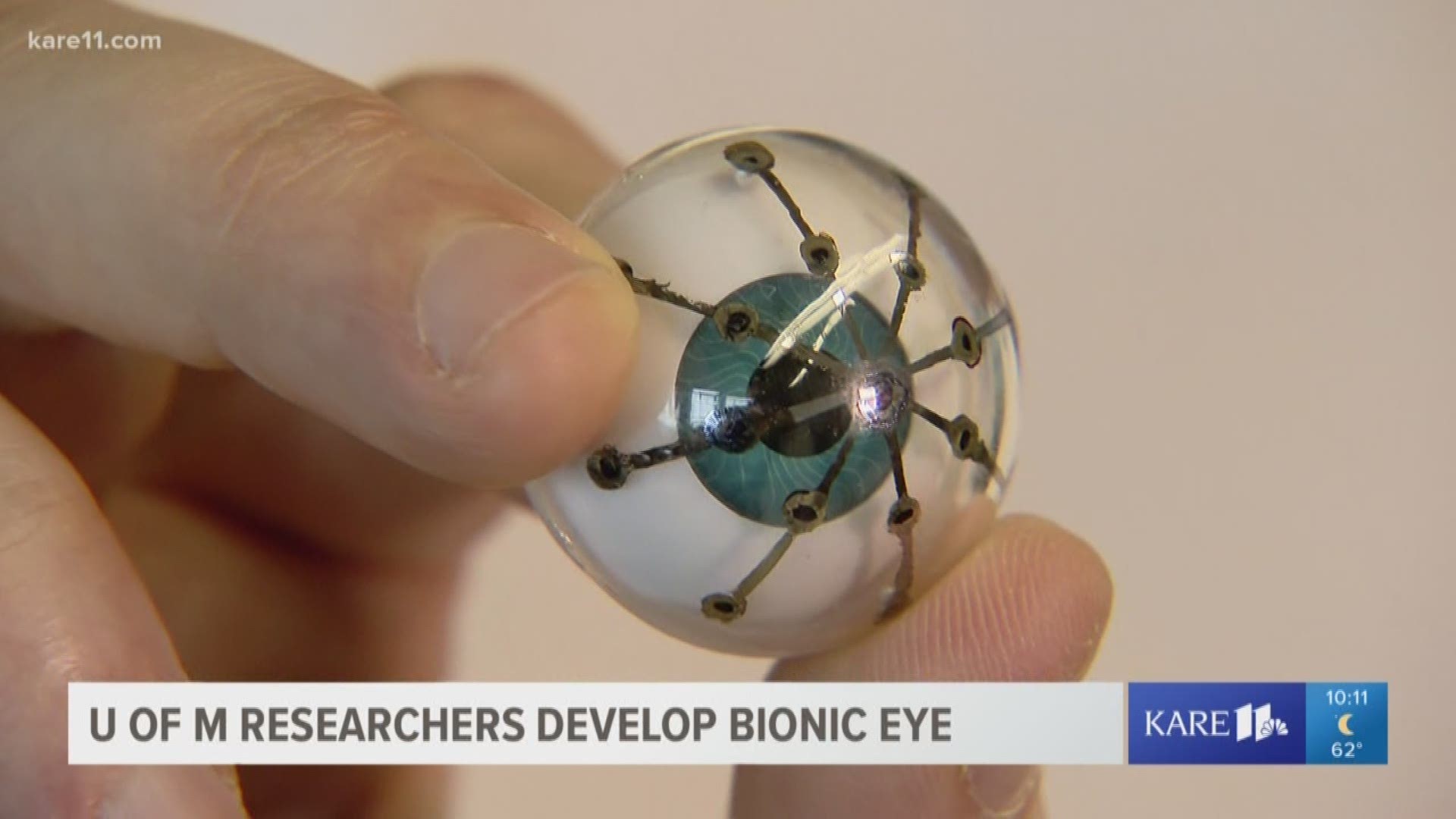

Using liquid metal, they found a new way to 3D print electronics onto a curved surface the size of an eye.

"Currently we're printing the top electrodes," said Ruitao Su, one of the graduate students working on the project.

Each electrode is a light receptor that could be used to help bypass a damaged retina.

"Efficiently converting light to electricity to create a bionic eye," McAlpine said.

It's the not the first time Minnesotans have heard that phrase.

In 2015, the Mayo Clinic became the first to perform a successful "bionic eye" surgery, which consisted of electrodes that were surgically implanted into a man's retina. The electrodes then connected to special glasses and external electronics in order to help the man see and sense light.

The surgery is now more common, but the technology remains limited.

"The only problem is, in order to see in three dimensional space you have to rotate your head," McAlpine said. "With something like this, now you can actually see into the periphery, see into three-dimensional space."

But it's not quite ready yet. The bionic eye currently contains 13 pixels.

"Next step would be to go from 13 to a hundred... or a thousand," McAlpine said.

"That will be critical for the resolution of the human eyeball," Su said.

Once they up the resolution, the team will start printing on a softer, tissue-like material so their ultimate goal can come into focus.

"We're one step away from being able to implant these," McAlpine said. "And we're not talking about ten years, we're talking about maybe two or three years."

Though this work is currently being done in a lab, McAlpine says the goal is to make this kind of printing technology widely available, so that medical devices can become cheaper, produced faster and more customizable than ever before.