MINNEAPOLIS — Dr. Justine Jones thrives on the chaos.

As one of two veterinarians at Modern Love Veterinary in the North Loop, Jones spends most of her work days rushing from room to room, fitting in exams with as many cats and dogs as the schedule allows. This small-animal practice in Minneapolis, which first opened in 2017, serves a variety of pet owners in the heart of one of the city's densest neighborhoods.

"I like staying busy," Jones said. "The busy days are kind of fun."

It's the only pace Jones really knows.

After graduating from the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine in 2020, Jones launched her career in the middle of COVID -- a time when pet ownership soared in the U.S. According to the ASPCA, roughly 23 million American households adopted new pets during the first year of the pandemic, putting a heavy strain on veterinarians who continue to care for those animals each day.

"I'm used to the heavy demand, but I know that isn't the norm, and that has been a shift since 2020," Jones said. "Certainly, there are days when we have to say no to pets, which is always hard. If we have a full schedule and we don't have the capacity to see them, we'll have to send them to the emergency room."

Such is life in the veterinary world right now.

As demand soars for veterinary care, particularly for pets, the industry continues to face a severe workforce shortage. Federal data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture lists veterinarian shortages in roughly 500 regions across 46 states, including 15 designated shortage areas in the state of Minnesota.

Dr. Laura Molgaard, the dean of the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine, said the pandemic exacerbated existing staffing challenges.

"This workforce shortage is not limited to any one particular geographic area or to any particular species. So, we are still seeing increased wait times," Molgaard said, "especially for emergency services."

However, the shortage is felt most deeply in rural areas, where veterinarians either work in mixed settings or with farm animals that provide the nation's food sources. In Faribault County, for example, KARE 11 has reported extensively on the county's last remaining veterinarian, who gave away his practice for free in 2022 only to see his replacement leave a few months later.

"Because veterinarians can practice on multiple species, when there is an increased demand for veterinary services with pets and increased pet ownership, that pulls the demand away from food animal," Molgaard said. "The impact on the veterinarian workforce shortage really does threaten the health of not only animals but people."

A lack of veterinary care in rural America could have devastating consequences on the nation's meat production, not to mention the fact that animals and humans can also share diseases.

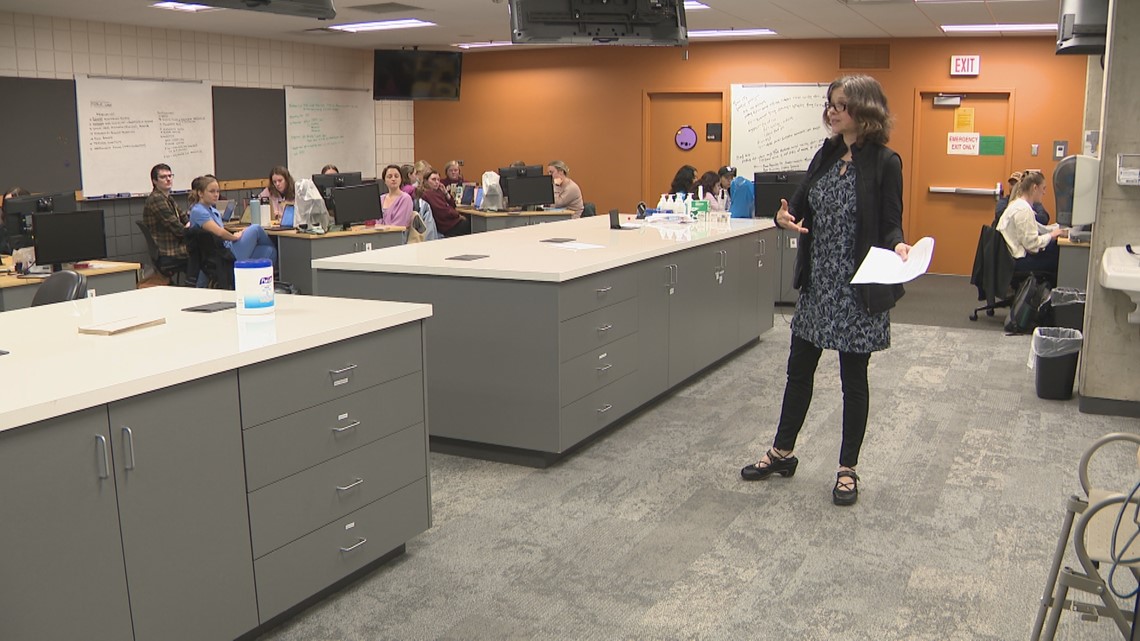

To bolster the rural workforce, the University of Minnesota has partnered with South Dakota State University to add 20 students to the Class of 2025, increasing enrollment from 105 to 125. The College of Veterinary Medicine -- the only veterinary school in Minnesota and one of roughly 30 nationwide -- also has a program known as VetFAST, which specifically aims to train and mentor students interested in caring for food animals.

"That's been very successful," Molgaard said. "We've got a lot going on. We are training the next generation of veterinarians, we are training the next generation of biomedical scientists, and training the next generation of veterinary specialists."

Undeniably, though, the rising cost of veterinary school serves as a barrier to some students. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) estimated that the average graduate in 2022 carried about $147,000 in debt, although that number dropped six percent compared to 2020.

"Student debt is a big challenge for this profession, and that's because training medical professionals is expensive, whether we're talking about veterinarians, dentists, physicians, nurses, or any health professional," Molgaard said. "Yet, the incomes of veterinarians do not keep up with those other health professions."

State and federal loan repayment programs already exist to offer support to students facing debt, but there are bipartisan efforts to expand some of those benefits.

On the federal level, the AVMA is pushing Congress to pass the Rural Veterinary Workforce Act, which would ease the tax burden on the Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program in an effort to broaden the scope. That program, known by the acronym VMLRP, provides up to $75,000 in debt relief over three years to graduates who practice in underserved areas.

Dr. Lori Teller, the immediate past president of the AVMA, said the current system requires the USDA to pay taxes on the loan program to the Internal Revenue Service, which she said is "completely different than how equivalent programs are handled for physicians and human health care providers."

"We just want to be treated like other health care providers," Teller said. "If the USDA does not have to send money to a different bucket of the government, to the IRS, and can instead keep that money, we could increase the number of veternarians who are helped and could go to rural areas by 25 percent."

At the same time, Teller seems more optimistic about the state of small-animal veterinary care in the U.S. and has cited a projected growth in these veterinarians through the end of the decade.

"Of course, there are going to be pockets of areas where you may have extended wait times, but overall, recent data has shown that the vast majority of clients can get in the same day or same next two days," Teller said. "Wait times have gone down, and urgent care is becoming much more normal."

However, even when facilities are fully staffed with veterinarians, a shortage in veterinary technicians has also created widespread problems for the industry. Veterinary technicians play a vital role by handling intakes, X-rays, anesthesia, blood draws, and other important day-to-day duties, but most only last four to five years in the industry, according to Dr. Allen Balay of the Minnesota Veterinary Medical Association (MVMA).

"The veterinary technician is such a multi-tasked individual," said Balay, who chairs the MVMA's Veterinary Technician committee. "It's oftentimes the veterinary technician who is the first person who may greet the pet owner and their animal, or the farm owner and their animal."

Currently, Minnesota is one of just nine states in the U.S. that does not license veterinary technicians, which Balay said may contribute to poor retention rates in the industry. During the 2023 state legislative session, the Senate included a licensure proposal in one of its spending bills, but the legislation never received a hearing in the House. The MVMA and Minnesota Association of Veterinary Technicians plan to lobby again for that bill in 2024.

"It's probably a real surprise to pet owners and farm animal owners, when they find out the veterinary technicians who may be working on their animal, doing the anesthesia, doing the dental procedures, doing the lab work, when they find out those folks are not officially recognized and regulated in the state of Minnesota," Balay said. "We believe that licensure would help keep and retain the technicians in the career field longer."

At Modern Love Veterinary in Minneapolis, Dr. Justine Jones said she sometimes has to scale back her patient schedule when there aren't enough veterinary technicians on duty.

"The veterinary technician," Jones said, "is essential for our job."

With the workforce shortage and increasing demand for care, Jones knows these are challenging times in her industry.

But she would not trade this life for anything else.

"I love my job. It's so wonderful. It's rewarding. Some days are harder than others, but that's any job. I get to work with amazing people and pets every day," Jones said. "I think the biggest thing that's pushing people away from veterinary medicine is the debt-to-income ratio. Education is quite expensive, [but] it's doable and it's a position I really like. So I would encourage people to still do it."

Watch more local news:

Watch the latest local news from the Twin Cities and across Minnesota in our YouTube playlist: