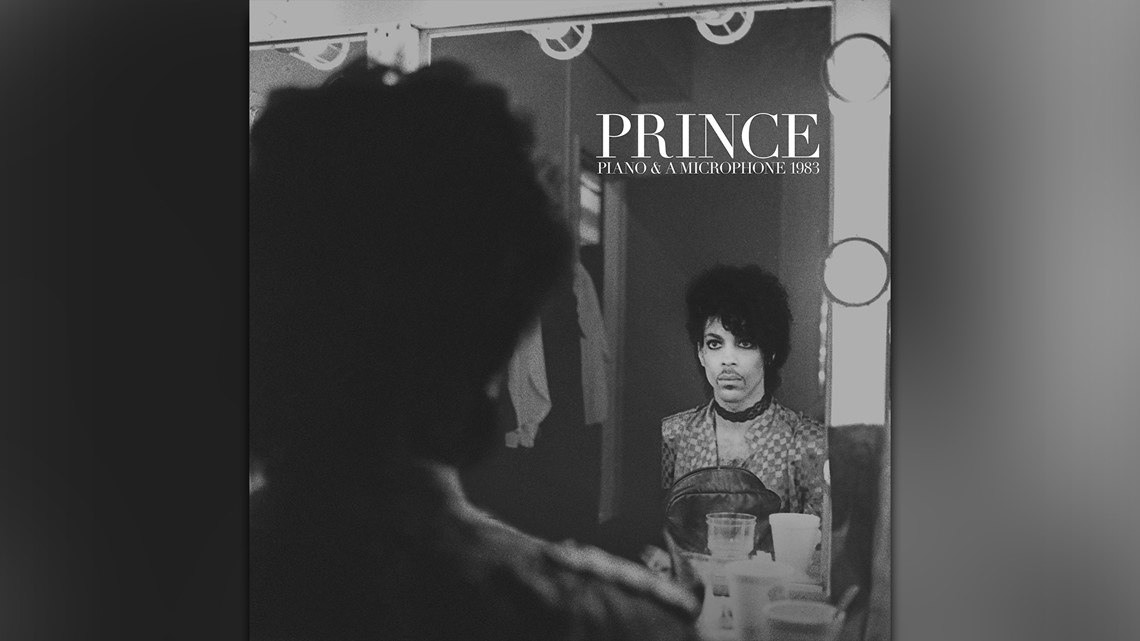

One of 2018's most compelling recordings started as an unmarked cassette tape.

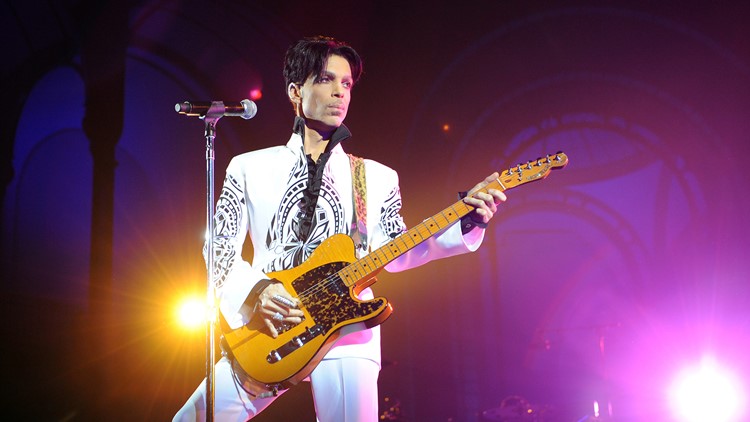

"Piano & A Microphone 1983" is a 35-minute, one-take recording Prince recorded, as the title promises, in 1983. And true to its name, the songs – early versions of "Purple Rain," ''International Lover" and "Strange Relationship," a cover of Joni Mitchell's "A Case of You" and his take on the spiritual "Mary Don't You Weep" – feature just the artist and his piano, an instrument that's far less commonly associated with Prince than his famous guitar but one that he shows off a shocking mastery of from the tape's earliest moments.

The nine-track album, out Friday, is more than just an essential listen for Prince fans – it's a fascinating look at the artist on the precipice of super stardom, during one of his most storied creative stretches as he works through the material that would appear on his masterwork, "Purple Rain."

Without Michael Howe, who worked with Prince at Warner Bros. Records and became the Prince estate's archivist after the artist's death on April 21, 2016, the "Piano & A Microphone 1983" tape may never have been uncovered.

In Howe's words, this is the story of "Piano & A Microphone 1983" – how the album came to be, what makes this particular recording session so special and how Prince's estate reckoned with what Prince himself would have wanted.

You can listen to the album below:

The recording session was legendary among collectors but only existed as bootlegs until Howe went hunting.

When Howe became the archivist for the estate, finding this specific 1983 Prince session was a mission of his.

"I was aware, as a fan, of its existence, because it had circulated among collectors and the bootleg community for a number of years, although it was in egregiously substandard condition from a sonic standpoint," Howe said. "I always liked very much the performance and the emotional gravitas or heft that it had. And one of the things that I wanted to do when I was becoming archivist was attempt to find a master recording, which I suspected was on cassette.

"Knowing what I did about the era and just spirit of the recording, we did a bit of detective work in the vault and were able to narrow down the wide pool of possibilities to a few candidates. Fortunately when we analyzed them, we spotted one that had Prince's handwriting on side two of the cassette, with the (songs on) side two, which are called "Cold Coffee and Cocaine" and "Why the Butterflies." So at that point we were pretty confident we'd found it, and sure enough when we put it in the machine, it was the one."

Both were previously unreleased songs and are particularly special finds for Howe.

" 'Why the Butterflies,' it's not available really anywhere else, and I haven't come across it anywhere else," he said. "With almost everything else on the album, I'm familiar with the background of the songs and what they evolved into. I don't know anything about 'Why the Butterflies' ... it's kind of a beautiful mystery. And, presumably, it will always remain that way."

The album captured Prince, the musician, right before he became Prince, the icon.

The "Piano & A Microphone 1983" session occurred before the release of the "Purple Rain" movie and album when the artist would achieve a new level of fame. It also marked a particularly creative stretch for Prince, "the year when the majority of the 'Purple Rain' material was recorded," Howe explained, "and he had just finished the 1999 Tour, so he was coming off a very creatively satisfying endeavor."

"At that point, he had become a star, but he hadn't yet strapped on the rocket engines that propelled him to superstardom, which was basically around the corner with the release of 'Purple Rain,' when he became a household-name, arena-devouring global superstar," Howe said. "So 1983 was really the last year that Prince had some level of, not necessarily anonymity, but being a bit less high-profile than he would in the very near future for him."

The most familiar title to casual fans on "Piano & A Microphone 1983" will be "Purple Rain," which appears on the album as a short snippet bearing little resemblance to the masterwork it became. Yet as Howe explains, the song went from the rough draft on "Piano & A Microphone" to the version fans hear on "Purple Rain" in a matter of weeks.

"Even though the track was in its embryonic stage on the 'Piano & A Microphone' album, it evolved into what became his most immortal track only really a few months later," Howe explained, pointing out that the final version of "Purple Rain" was largely recorded at one of Prince's Minneapolis concerts just weeks after his "Piano & A Microphone" session.

Howe and Co. wanted to release an album Prince would have been proud of.

Honoring Prince's memory, and sharing his music in a manner in which he would've approved, was essential to Howe as the Prince estate navigated the release of "Piano & A Microphone 1983."

"It's a very small group of people who are talking about this stuff, and we're very serious and very cognizant of wanting to do the right thing by him, and we have to use our best judgment sometimes," he said. "But these are people who knew Prince, who worked with him, who had a lot of interaction with him, and if anybody has a barometer of what he would approve of, it's this core group of people."

Prince was fiercely protective of his storied vault when he was alive, and while Howe "can't disprove completely" the idea that the artist didn't want his unreleased music shared after his death, he does believe Prince knew and accepted that his vault eventually would be opened.

"There were at least a couple of instances where Prince mentioned either during interviews or in another context that he would be OK with a portion of the vault recordings emerging and that it would probably be after his lifetime, but that he seemed to recognize it was a possibility and seemed to be somewhat at peace with that," he said. "In my experience, and talking with the people who are most knowledgeable about this stuff, I don't think it was ever explicitly instructed to anybody that these things should never see the light of day."

"He kept them for a reason," Howe continued. "I mean, there were things that he discarded, and there were tapes that were recorded over presumably because there was no chance that he would ever want to revisit them. But these things exist, and they are really a huge part of the cultural fabric, and quite a few of them, in my estimation, are deserving of an audience."