GARDINER, Mont — Most of Yellowstone National Park should re-open within the next two weeks — much faster than originally expected after record floods pounded the Yellowstone region last week and knocked out major roads, federal officials said Sunday.

Yellowstone Superintendent Cam Sholly said the world-renowned park will be able to accommodate fewer visitors for the time being, and it will take more time to restore road connections with some southern Montana communities.

Park officials said Sunday they'll use $50 million in federal highway money to speed up road and bridge repairs. There’s still no timetable for repairs to routes between the park and areas of Montana where the recovery is expected to stretch for months.

Yellowstone will partially reopen at 8 a.m. Wednesday, more than a week after more than 10,000 visitors were forced out of the park when the Yellowstone and other rivers went over their banks after being swelled by melting snow and several inches of rainfall.

Only portions of the park that can be accessed along its “southern loop” of roads will be opened initially and access to the park’s scenic backcountry will be for day hikers only.

Within two weeks officials plan to also open the northern loop, after previously declaring that it would likely stay closed through the summer season. The northern loop would give visitors access to popular attractions including Tower Fall and Mammoth Hot Springs. They’d still be barred from the Lamar Valley, which is famous for its prolific wildlife including bears, wolves and bison that can often be seen from the roadside.

“That would get 75 to 80% of the park back to working,” National Park Service Director Charles “Chuck” Sams said Sunday during a visit to Yellowstone to gauge the flood’s effects.

It will take much longer — possibly years — to fully restore two badly-damaged stretches of road that link the park with Gardiner to the north and Cooke City to the northeast.

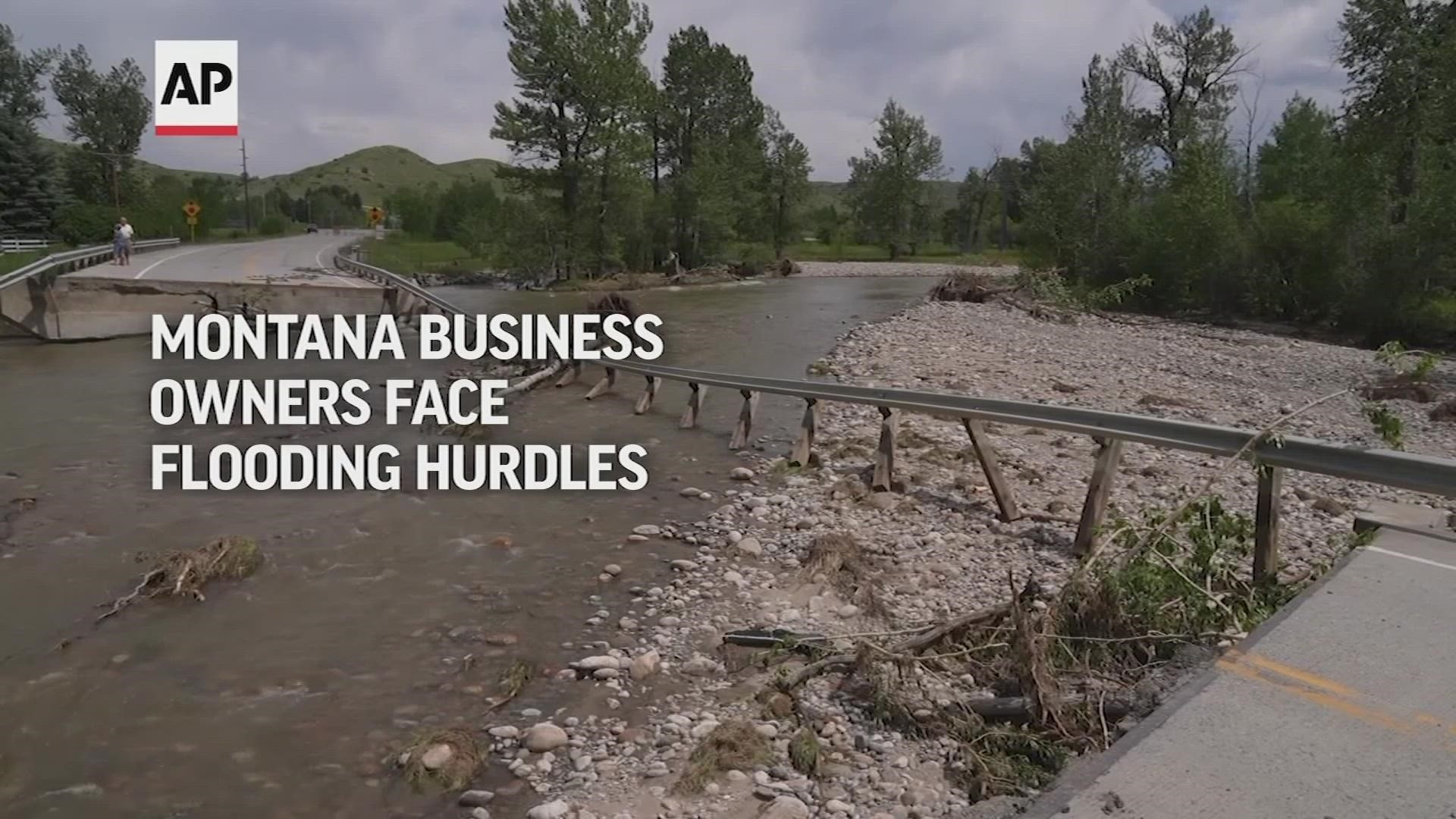

During a tour of damaged areas on Sunday, park officials showed reporters one of six sections of road near Gardiner where the raging floodwaters obliterated most of the roadway.

Muddy water now courses through where the roadbed had been only a week ago. Trunks of huge trees litter the the surrounding canyon.

With no chances for an immediate fix, park Superintendent Cam Sholly said 20,000 tons of material were being hauled in to construct a temporary, alternate route along an old road that runs above the canyon. That would let employees who work at the park headquarters in Mammoth get to their homes in Gardiner, Sholly said. The temporary route also could be used by commercial tour companies that have permits to lead guided visits.

“We've gotten a lot more done than we thought we would a week ago,” Sholly said. “It's going to be a summer of adjustments.”

Meanwhile, some of those hardest hit in the disaster — far from the famous park’s limelight — are leaning heavily on one another to pull their lives out of the mud.

In and around the agricultural community of Fromberg, the Clarks Fork River flooded almost 100 homes and badly damaged a major irrigation ditch that serves many farms. The town's mayor says about a third of the flooded homes are too far gone to be repaired.

Not far from the riverbank, Lindi O'Brien's trailer home was raised high enough to avoid major damage. But she got water in her barns and sheds, lost some of her poultry and saw her recently deceased parents' home get swamped with several feet of water.

Elected officials who showed up to tour the damage in Red Lodge and Gardiner — Montana tourist towns that serve as gateways to Yellowstone — haven’t made it to Fromberg to see its devastation. O'Brien said the lack of attention is no surprise given the town's location away from major tourist routes.

She's not resentful but resigned to the idea that if Fromberg is going to recover, its roughly 400 residents will have to do much of the work themselves.

“We take care of each other," O'Brien said as she and two longtime friends, Melody Murter and Aileen Rogers, combed through mud-caked items scattered across her property. O’Brien, an art teacher for the local school, had been fixing up her parents' home with hopes of turning it into a vacation rental. Now she's not sure it's salvageable.

“When you get tired and get pooped, it's OK to stop,” O'Brien said to Murter and Rogers, whose clothes, hands and faces were smeared with mud.

A few blocks away, Matt Holmes combed through piles of muck and debris but could find little to save out of the trailer home that he shared with his wife and four children.

Holmes had taken the day off, but said he needed to get back soon to his construction job so he could begin making money again. Whether he can bring in enough to rebuild is unclear. If not, Holmes said he may move the family to Louisiana, where they have relatives.

“I want to stay in Montana. I don't know if we can,” he said.