MINNEAPOLIS — The ten-year plan designed to fend off $180 billion in losses for the United States Postal Service drew protests from Minnesota union members Monday.

Union postal workers and allies picketed the main Minneapolis Post Office, saying the changes to the delivery standards for 1st class mail will have a disproportionate impact on older customers, especially those in rural areas.

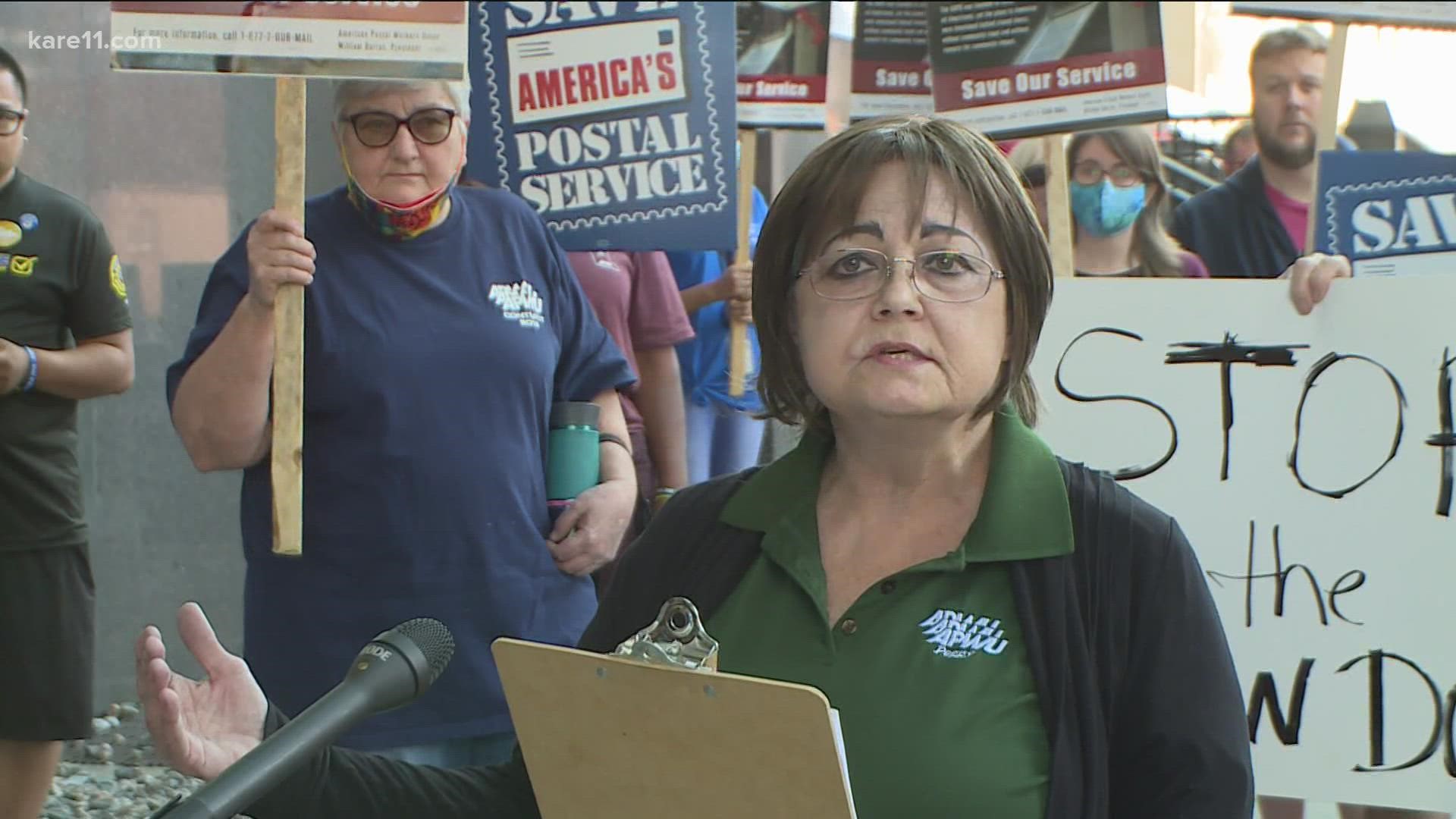

"If you have urban communities still getting their mail in two days, and rural America not getting it for five days, you have failed in the mission of the postal service," Peggy Whitney, the business manager for the Minneapolis American Public Workers Union, told reporters.

"In rural communities they rely heavily on mail delivery that provides them with their Social Security checks, their medications, many things that need to be delivered in a timely manner."

The strategic plan, which went into effect Oct. 1, changes the standard of service for mail, allowing up to five days for delivery of mail pieces traveling between regions. The USPS projects that 70% of the mail sent within a metro area will be delivered within three days.

One of the reasons for the slowdown is that part of the mail now traveling by air will be moving instead to trucks on the ground. That change will have the greatest impact on coast-to-coast mail, or pieces traveling to Texas and Florida because of the distances involved.

Whitney said Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, the architect of the cost-saving reforms, was actually inside the main Minneapolis Post Office Monday greeting staff members. A USPS spokesperson wouldn't confirm that, saying only that DeJoy's travel itinerary is not public.

According to a document placed in the Federal Register the USPS Board of Governors will meet in Minneapolis Tuesday afternoon. The document is a legal opinion from the panel's legal counsel that the meeting may be held in private without violation of federal agency open meeting laws.

In a news release explaining the changes, the USPS said the traditional levels of service and speed simply aren't affordable any longer. It's a financial bind that was aggravated by the COVID pandemic when people began to rely more heavily on parcel delivery as an alternative to shopping in person.

"Our reach is unparalleled—delivering nearly half of global mail volume, and goods and services to more than 160 million addresses across the country; and ninety-nine percent of the population has a Post Office within 10 miles of where they live," the statement read.

"And yet, our organization is in crisis. The Postal Service has recorded $87 billion in financial losses over the last 14 years and failed to meet service standards. Our business and operating models are unsustainable and out of step with the changing needs of the nation and our customers."

The system's dire financial straits have been exacerbated by an action of Congress in 2006. The Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act required the USPS to create a $72 billion fund to pay for the cost of employees' post-retirement health care costs for 75 years into the future.

No other federal agency faces such a pre-payment requirement, let alone private employers. At the time, lawmakers were looking to address a wide array of underfunded pension plans during a time of unprecedented increases in medical costs.

In addition to slowing the roll of flat mail, customers have been told to expect higher prices for sending parcels, especially during the holiday season rush.

DeJoy's efforts at reform during the final year of the Trump Administration drew fire from unions and Democratic politicians. He drew fire for removing idle sorting machines from regional distribution hubs. Union leaders said when mail volume picked up again post-pandemic that equipment would be needed.

The Board of Governors approved the current 10-year plan, based on projections that the money saved will be invested in technology that will make the postal system more efficient and competitive with other package delivery companies.