GOLDEN VALLEY, Minn. — SportsLife is a recurring blog examining issues that impact young athletes, their families, officials and the greater community. Topics come from YOU: email them to news@kare11.com with SportsLife - Dana Thiede in the topic line.

Talk with Mark Wick for a couple of minutes - even if it's on Zoom, and not face-to-face - and the energy and positivity that pours from him is palpable. Thoughtful, funny and self-deprecating, the veteran hockey coach is the kind of guy you'd want at the helm of your kid's team. He obviously "gets it," understands what's important about sports and how competing can pave the way for success and a balanced life.

Wick will tell you straight up, it wasn't always that way.

"I look back, and nothing against coaches, I’ve been one for 33 years and I’m gonna be honest with you, I think I was successful on the ice but I look back at a lot of the things I did and I wasn’t a good coach to a lot of people," Wick shares. "It wasn’t that I didn’t try to be, but I didn’t know what to look for. I couldn’t see 'em in myself, I certainly wouldn’t see them in other people."

What Wick didn't see, either in himself or his young athletes, were signs of struggle with mental health issues that just about everyone has. As it turns out, the coach had struggled with aspects of depression for much of his life but he didn't know it, or chose to ignore the symptoms. That changed during his 11th season at the helm of the St. Scholastica men's hockey team on a cold January night.

"In 2015 we were playing in upstate New York, after a loss that night things kind of spiraled. I was walking back to our hotel after the game, stopped at a bridge over the Oswego River and really thought the best thing for everybody was if I was just gone," Wick recalled in a matter-of-fact tone. "The burden of me would be gone. I contemplated jumping off the bridge and I didn’t, obviously, but not because it was a bad idea... it just wasn’t the right time. We were out in New York, that would cause more hassles. Had we been closer to Duluth I don’t know what would have happened."

Wick dodged that bullet but didn't address the issues that nearly made him jump. Mere weeks later came a meltdown that was impossible to ignore.

"In the end of January, the 31st, I had an incident on the ice after a game where I kind of lost it."

"Kind of," he laughs, "I DID lose it and got back in the locker room and was kind of in a paralyzed state," Wick shares. "I was non-functional, I sat with my head in my hands, stuff was going on, and Jackie MacMillan, our women’s coach was in there, and left and called my wife and said 'You’ve got to come over here, something is going on with Mark.' She waited 'til everybody left, she came back in about the same time my wife did and that’s when… I didn’t realize I needed help, but I didn’t have a choice but to get help."

Mark Wick started seeing a therapist and learning about the roots and escalating outcomes of his depression, which manifested itself in lack of focus, irritability, rage and self-medication.

"If it’s anger and irritability? People accepted that in my sport," Wick chuckles. "You go to a hockey game, two guys start punching each other in the face, all they do is sit down for five minutes. Try that at the bank office. Try that at the nurses station. The difference is when I hollered and screamed at people, like referees? People cheered, they didn’t say, 'oh geez, something’s wrong.'"

When he felt healthy enough to return to coaching in the fall of 2015, the Duluth News Tribune wanted to talk with Wick about his journey with depression. His open, direct style of communicating led to a powerful story, which in turn, would lead to what is now his life's mission.

"The number of people that reached out and said, 'Hey that’s me, that’s my husband, that’s my child, that’s my spouse…' whatever," Wick remembers. "Then I got asked to talk some and I was very open about my challenges and my illness, and the more I went around... and I talk to everybody, hockey doesn’t have a corner market on this stuff… when I went out and talked to college campuses, the number of people who would come up later and share what they were going thru, and they didn’t know what to do."

Wick is now an in-demand public speaker who talks with young athletes, college students, anyone willing to have a conversation about mental health and why it still carries a stigma. I found out about Wick and his work from a mutual friend Steve Carroll, a respected goaltending instructor, DNR communications professional and former KARE 11 colleague.

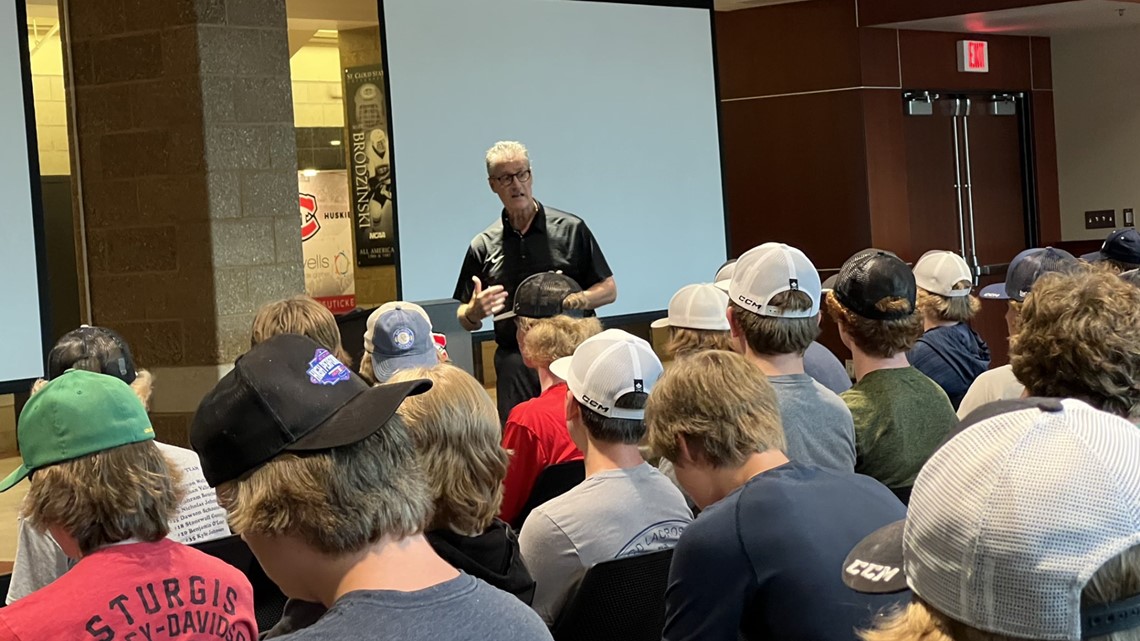

Wick presented for a group of 100 high school-aged goalies and skaters (both boys and girls) during a CCM High Performance Camp at St. Cloud State University recently, and Carroll was clearly moved and impressed by what he heard.

"Mark did an excellent job of connecting with the kids as he shared his personal struggle with depression in an emotional and engaging heartfelt presentation," Carroll told me. "He delivered a powerful message about mental health awareness and that it’s okay to not be ok and that help is available."

Carroll couldn't have been more impressed when Wick finished off the presentation by asking the kids to get out their cell phones, to open their contact list and add his name and number in case they ever needed help or someone to talk to.

"It was an awesome way to close out his talk, and showed he truly cared about the mental health of these kids," Carroll said.

Wick remembers that day, and the young athletes he connected with.

"That group of people, there were... kids that I guarantee have some pretty heavy stuff going on in their lives," Wick recalls. "I think there are a lot of kids out there that are hurting, that don’t know what to do. We don’t get up there and lecture about the things about mental health, it’s just sharing our story. I think that by sharing our stories it makes them more normal… and the more people talk about it the more they find out they’re not all alone. I felt like that (at the height of his depression), nobody gets what I’m doing through."

On his website, Wick states that he is not a doctor, therapist or counselor, but that will soon change. He is taking a year off the ice to finish up his masters degree in clinical mental health counseling while continuing to do mental performance work with skaters at Minnesota State, St. Cloud and Augsburg. Wick is adamant that an athlete's mental well-being should receive the same care and concern as treating a physical ailment.

"We know we can’t be successful on any of our sport environments if we’re not good physically. If I have a twisted ankle it’s tough to play basketball or volleyball. It’s tough to be a sprinter with a pulled hamstring, right?" he reasons. "Well, we know that, but a ton of noise or bad thoughts or trauma, grief we haven’t dealt with, we think that’s not gonna have an effect on our performance either? That’s where we have to start treating our mental health like our physical health."

When it comes to coaching and how he would do things over, Wick reflects on growing up in "old school" times when an athlete did anything a coach asked without question. Today, he says kids aren't afraid to ask why they have to do a drill or why they have to follow a team policy, and maintains a good coach should ask his or her own whys: Why an athlete isn't performing, why are they acting out or struggling in the classroom.

"There was a kid at practice one day, and I got on him. He wasn’t there. I got on him pretty hard cause he was one of the better players, and I remember him coming into the office afterwards and saying 'Hey coach, I’m sorry, I was bad today. I wasn’t there, but I wanted to let you know that right before practice I found out that my grandpa has cancer.' Well, no kidding you should be off. But if I would have asked WHY… asked what’s going on, you look like you’re not here today, why? You do what you need to do, if you need to leave, you don’t need to be here."

The last question I had for Wick involved him reflecting on something else from his site, a sentence that seems to sum up the coach's message succinctly: It reads: What mental health needs is more sunlight, more candor, and more unashamed conversation.

"There’s no greater sign of strength to me… and courage… than reaching out to ask for help," Wick says with conviction. "That’s not weakness. And we have to have the conversation so we know it’s OK and once it comes along, “What can I do for ya?"

"Let’s normalize this," he continued. "The more we talk about it the more we normalize it. The more we normalize it hopefully people will be able to reach out for help and hopefully stop these really dire things from happening."

If you or someone you know is facing a mental health crisis, there is help available from the following resources:

- Crisis Text Line – text “MN” to 741741 (standard data and text rates apply)

- Crisis Phone Number in your Minnesota county

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), Talk to Someone Now

- Throughout Minnesota call **CRISIS (**274747)

- The Trevor Project at 866-488-7386

Watch more SportsLife:

Watch all of the latest interviews from the ongoing digital blog on our YouTube Playlist: