The splash of the water, the drive to go faster and the desire to work hard are all things that make Mallory Weggeman the person she is today.

“At the end of the day, I just loved to swim,” says Weggemann. “It was kind of my place to go and be me.”

But her chiseled frame was forged on adversity. On Jan. 21, 2008, when she went to the hospital for an epidural to treat back pain she came out paralyzed, unable to walk, unable to continue the accomplished swimming career she loved.

"There was more things on the list of what I’ll never do again versus opportunities of what I could do again,” says Weggemann. “Sorting through all that was really tough.”

It wasn’t until she became aware of the Paralympic movement the she even thought about swimming again. In fact, initially she didn’t want to get back in the water, but at the urging of her family, she went to watch Paralympic swimming trials at the University of Minnesota.

“Not to say that when l looked over that railing I said, ‘I’m gonna become a Paralympian,” she recalls. “I said ‘maybe I can swim again.’”

Mallory raced in her first race just about four months after becoming paralyzed.

“I was racing 8- and 9-year-old kids," she said. "Every single one of them kicked my butt. It didn’t matter, I was back to doing something I loved.”

And taking the control back, from the injury that took so much from her

“That black line, I’ve said it time and time again, it saved me.” Mallory says. “It bridged my past to my present and it gave me something to look forward.”

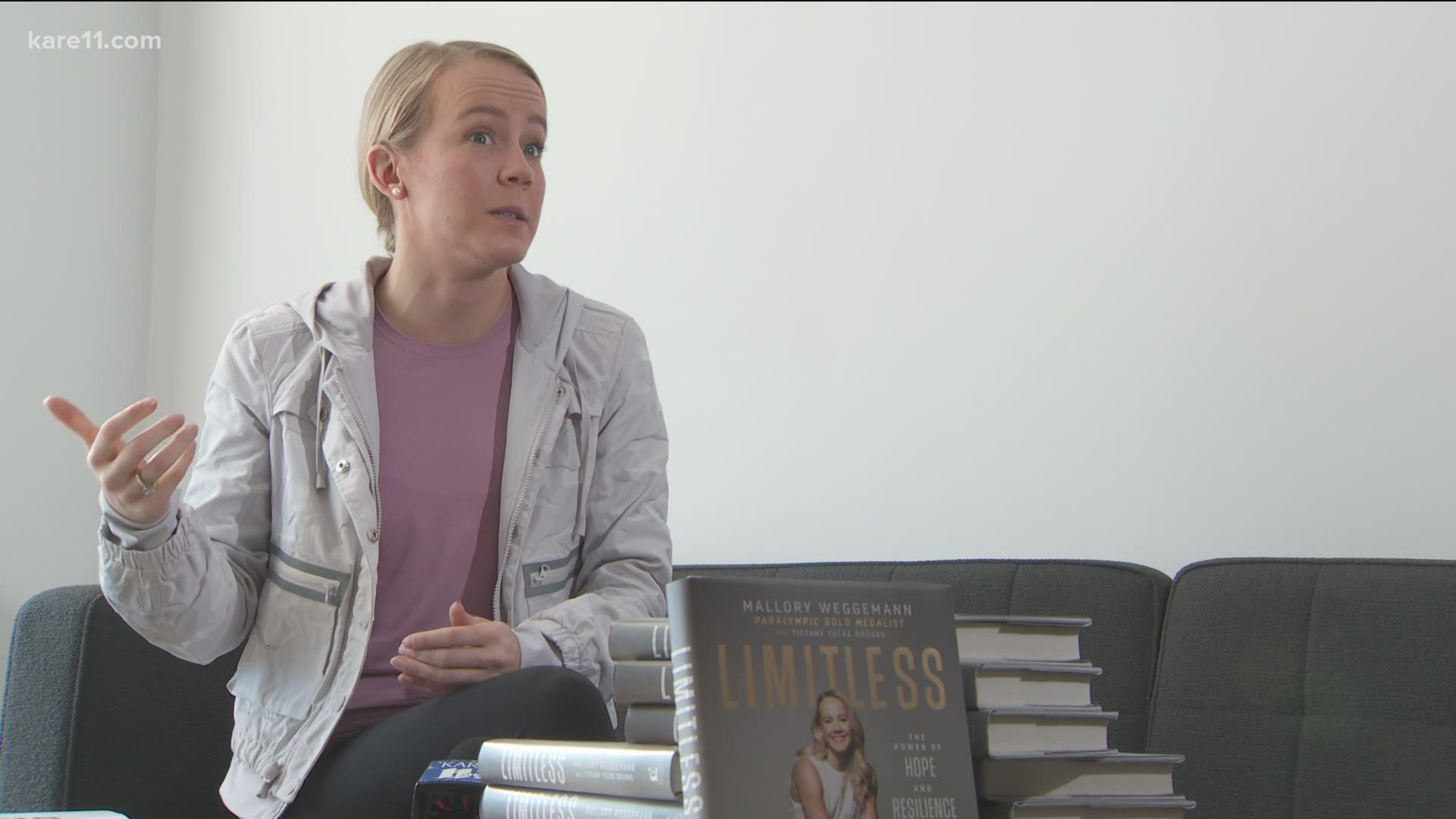

The rest is Paralympic history. Mallory is a two-time Paralympian medalist, winning a gold and a bronze. She’s broken 34 American Records and 15 World Records. And now, she's written a book, "Limitless" – out this week – about her journey, in the hopes of inspiring others like her.

“I want to use my craft in a way that can empower others to see their path forward so they don’t have to ask what about me," she says.

“Every book shelf 'Limitless' sits on, there’s a woman in a wheelchair," she says. "And some girl or boy or adult that feels different in our world can look to a shelf and see somebody else who looks different being celebrated for that.”

And as she prepares for her third Paralympics this summer in Tokyo, she’s keenly aware that not everyone cares whether she represents the U.S. on the podium, and instead are more interested in the hope she represents that life can continue after tragedy.

“To now be able to do what I do in a way where, maybe, by just seeing me on a starting block, some other person will look down and say maybe I can do that," says Weggemann. "And you never know what will spark for them.”