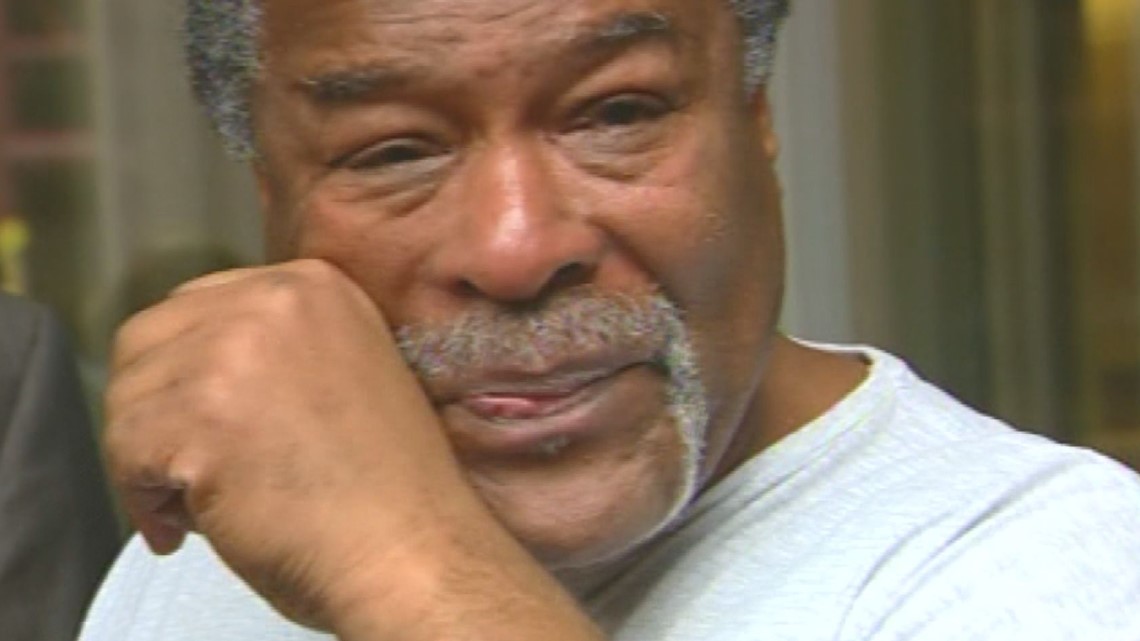

In 2007, Sherman Townsend walked out of state custody and into a crowd of reporters.

It looked like the quintessential exoneration scene.

His sister said through tears, “I’m so happy my brother is here right now.”

Townsend said, wide-eyed, “I don't think they took my life away. I think I go from this day forward doing the very best I can.”

His lawyer said, proudly, “I believed Sherman was innocent the very first time I looked at his file.”

Making the moment even more dramatic was the backstory. After 10 years, another man had come forward and taken responsibility for the burglary Townsend was accused of. That man, David Jones, was the prosecution’s star witness at trial. He had finally confessed, saying that he pointed to Townsend as the perpetrator in order to save himself.

But a shadow hung over Sherman Townsend on this joyful day. Although he was free, he was not exonerated. Because before a judge could rule on his fate, Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman had offered him a deal.

RELATED: New research shows prosecutors often fight winning innocence claims, offer deals to keep convictions

The crime

The burglary that sent Sherman Townsend to prison happened early the morning of Aug. 10, 1997. It was a summer night in the Minneapolis neighborhood of Dinkytown, near the University of Minnesota campus.

Police were called to a home where they found a burglar had cut the screen window on the bottom floor, crawled in and assaulted a boyfriend and girlfriend in the upstairs bedroom. The woman said she woke up to the man sitting on her, with his hand on her throat. She said he struggled with her boyfriend, too, before running away.

The victims described him as a Black man, muscular build, in his 20s or 30s, wearing a dark shirt.

One of the officers on the scene immediately thought of Sherman Townsend when she heard the suspect description. He had a burglary record in this neighborhood. But his last conviction was six years earlier. And he was 47 - considerably older than what the victims described.

About 15 minutes later, Townsend was detained by police a block and a half from the scene of the crime. The odds that he’d be so close by at that time of night, just by chance, seemed slim. Townsend said it was because he had friends in the neighborhood. He hung out there frequently, drinking beers and playing music.

Meanwhile, a neighbor of the victims, David Jones, told officers he had seen the suspect. He was walking by when he said a Black man ran into him coming out of the burglarized home. When police pulled up in the squad car with Townsend, they asked Jones if this was the man who had run into him. He said he was 100% positive that was the guy.

Neither of the victims could identify Townsend at the scene.

Townsend turned down a plea deal before the trial. According to the court transcript, he told the judge, “I’m innocent. I have to go for the whole ball of wax.”

He didn’t have money for bail, so he was locked up from the time he was arrested.

The trial lasted a week. Townsend’s defense attorney Stanley Nathanson got the first jury tossed out, because it was made up of all white people. The new jury heard from both victims, who still could not identify him, and they heard from police. But the trial mostly hinged on the testimony of David Jones, since there was no physical evidence.

Because there was a roll of duct tape found at the scene of the burglary, the state suspected Townsend had planned to sexually assault the woman in the house. The judge said there wasn’t enough evidence to include that in the charges, but the prosecutor still mentioned it in his closing argument.

The prosecutor also got the judge to let him introduce “Spriegl” evidence, which is evidence of past crimes. The jury heard about one of Sherman’s prior burglaries, just blocks away from the house. In that one, Sherman pleaded guilty. He had taken a total of $6 from the apartment of three sleeping college girls. There was no assault.

Townsend chose not to testify in his own defense. If he did, the prosecutors could ask him about even more of his past burglaries. So he was silent.

The jury believed David Jones. They convicted Townsend of first-degree burglary.

Judge Deborah Hedlund said she thought the guidelines probably called for nine years. But when she called Townsend back for sentencing the next month, she gave him 20, based on his past crimes.

A decade of appeals

Townsend said during his time in prison, he missed “everything.”

“Being at the beach, spending time with family, spending time with my grandchildren, I wanted to do everything I was doing in normal life,” he said. “The TV doesn’t help because you’re watching everybody else do everything.”

After the defense attorney finished his closing argument at trial, Townsend tried to fire him. He ended up backing down, but he made it clear to the judge that he was not happy with his counsel. He even filed an appeal based on ineffective counsel, but he was denied.

However, in 2012, Stanley Nathanson was suspended indefinitely from practicing law in Minnesota for failing to act with reasonable competence. That suspension was unrelated to Townsend’s case.

Townsend kept filing appeals. Two Hennepin County attorneys fought him over those years: Mike Freeman and Amy Klobuchar. Freeman said in one response, “no material facts are in dispute in this case.” In 2002, Klobuchar said Townsend’s petition should be denied “in the interests of finality.” In 2006, she fought another petition, saying the claim was “clearly meritless.”

Every appeal was denied. Then, in 2007, something extraordinary happened.

Enter David Jones

Townsend had been in prison for about nine years, and he knew he wouldn’t be eligible for parole until at least year 13. For some reason, he’s always remembered an experience he had early on in his sentence. A spiritual moment.

“You probably won’t believe this but when I first went to prison, when I first got into St. Cloud ... all the sudden the sun just shined bright in my cell, right?” he said. “And all the sudden it was like a voice told me, kept telling me, 10. You know? Well, it didn’t mean anything to me then. But it was right at 10 years that this thing got overturned.”

Townsend now believes it was a message from God.

“I just believed it,” he said. “And then just about what, nine or nine and a half years in, that’s when David Jones shows up.”

The Great North Innocence Project was already looking into Townsend’s case at this point. Legal Director Julie Jonas remembers it well.

“He was one of the first letters we got when we opened,” she said of Townsend’s plea. “And his was really compelling because he said, ‘Look, I’ve been to prison before. If you look at my record, when I do something wrong, I plead guilty. I go to prison. I didn't do this one.’”

Jonas said the “turning point” in Townsend’s case was a letter from David Jones.

“He knew Sherman was innocent because he is the one who committed the crime,” Jonas recalled from the letter. “He had purposefully framed Sherman. … He thought if he went outside and told the police it was a different Black man and acted as if he was trying to be helpful, he would throw suspicion off of himself. And it worked. It worked perfectly.”

After Jones testified against Townsend in 1998, he went on a couple years later to be convicted of criminal sexual conduct. He ended up in the same prison as Townsend, and recognized him. When he found out that Townsend was doing time for that same burglary, and how long he’d been there, Jonas said he had a “crisis of conscience.” He agreed to testify in court.

“He met with us for hours,” Jonas said. “He described the inside of the victim's home in ways that nobody else could have.”

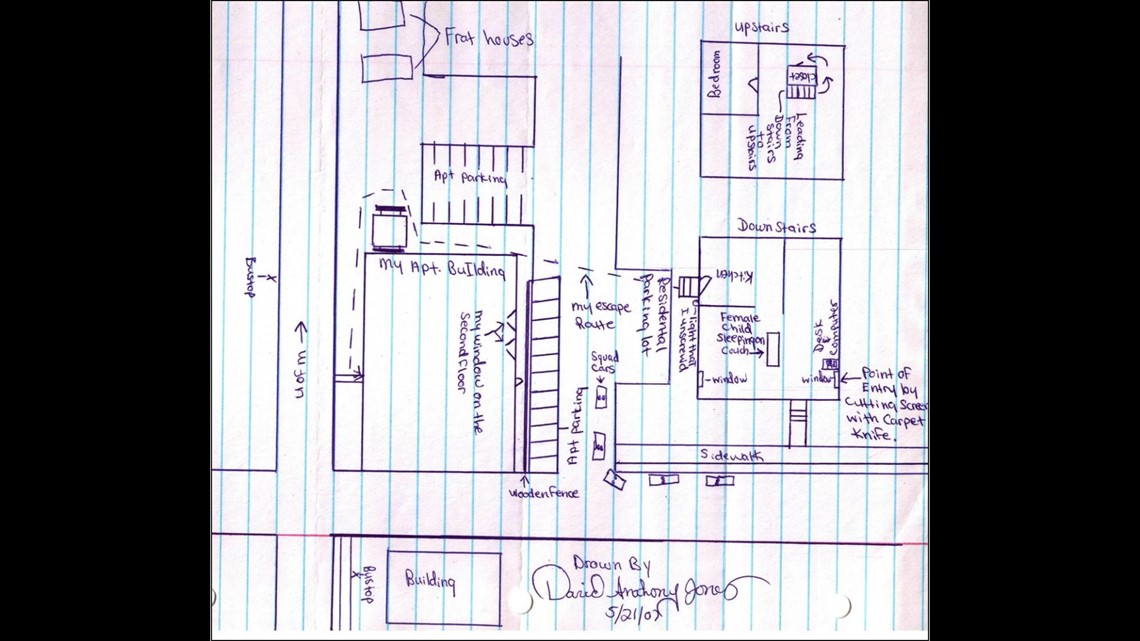

On Sept. 24, 2007, the Innocence Project lawyers presented the new evidence before the same judge, Deborah Hedlund. They had a confession from David Jones, who took the stand and testified for two hours. A detailed map he drew of the crime scene. And a chilling description of how he had stalked the women who lived in that home, planning to rape them.

For Townsend, just this hearing in itself was cathartic. Some of his family members were there, hearing someone else confess to the crime he’d been locked up for over the last decade.

“I think that helped them quite a bit, believing that I had no part in that crime,” Townsend said.

At that hearing, the Hennepin County prosecutor drew attention to discrepancies between David Jones’ story and what the victims said years ago. He said Townsend could have fed Jones all the details he shared, suggesting that they cooked the story up together in prison.

But Julie Jonas pointed out that David Jones’ case worker signed an affidavit saying that she never saw any evidence that Townsend threatened him - and that Jones told her privately that he was not being coerced.

When Jonas got up to give her closing argument on Townsend’s behalf, she said she believed this was a case of actual innocence. “Your Honor, as I stand before you,” she said, “I think that this is one of the most important things I have ever done.”

After that hearing, Townsend could do nothing but wait for Judge Hedlund to rule on whether she thought the new evidence warranted a new trial.

But a few days later, Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman came to Townsend with a deal. If he would withdraw his motion for a new trial, Freeman would ask the judge to re-sentence him to time served. He would walk out a free man. But he’d have to accept the conviction for the crime. If he turned it down, and then received a new trial, the conviction would be wiped from his record. It would be up to Freeman to decide whether to try to convict him again, starting from scratch.

“You know, all we can do as attorneys with clients is present that offer to our client, right?” Jonas said. “We bring it to our client and we really try and leave it up to the client to decide. I would say that most attorneys of innocence projects would say, ‘I would like my client to hold out and not take the deal.’ Because if they receive a full exoneration, they have the potential for compensation and they have the potential to get it off of their record.”

Townsend had second thoughts about accepting the deal for those reasons.

“Yeah, I just think I gave up too much,” he said.

Townsend said he took the deal because he’d been in prison 10 years, and his mother’s health was slipping.

“One of the main things I asked God for at the beginning of prison was, ‘Please don’t let my mother die while I’m in prison,’” he said. “And she ended up dying five months after I got out.”

The plea deal went through on Oct. 2, 2007. Just over 10 years after Sherman was taken into custody, he walked out into the sun, and a crowd of reporters. He told them he felt like he was getting “a new chance at life.”

But Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman spoke to the press that day, too.

“He served 10 years for a crime we believe he did,” Freeman said. “It's appropriate that the judge let him out."

That’s not all he said. He told reporters that it would be impossible to retry Sherman. And of course that’s likely true - their prosecution hinged on David Jones, who now claimed responsibility for the crime himself. Mike Freeman was quoted in the Pioneer Press saying, “We believe Mr. Townsend did it. We no longer have the evidence to prove that beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Watch below: KARE 11's 2007 report on Sherman Townsend's release

Freeman declined to comment on Townsend’s case for this story.

Keith Findley, a law professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School and a co-founder of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, said deals like this are familiar to him. He’s gathered data on 272 cases from innocence organizations around the country, where they were litigating claims based on new evidence of innocence. He found that prosecutors offered deals to preserve a conviction nearly 24% of the time.

Findley did not comment on Townsend’s case specifically, but said he finds it “problematic” when prosecutors publicly say someone is guilty, yet don’t have the evidence to pursue a new trial.

“The way our system works is that until you're convicted, you're entitled to a presumption of innocence,” Findley said. “And the only way that our system can determine whether somebody is guilty or innocent is to go through the process of going through trial and having the prosecutor prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, or the defendant waives the trial and pleads guilty.”

Findley said short of that, the person is entitled to a presumption of innocence.

“And so for a prosecutor to publicly say, ‘I believe this person is guilty, but I can't prove it‘ is a failure to abide by one of the most basic tenets of our legal system,” Findley said. “And is an unfairness to that person who is just as entitled to the presumption of innocence as you or I.”

Findley added, “So prosecutors ought to take their cases to trial or get a valid plea bargain and live by the conclusion. Their own personal opinions about guilt or innocence are really beside the point. And to continue to express belief in guilt without proving it through the legal process is simply unfair and inconsistent with the presumption of innocence, and with the prosecutor’s oath to support and enforce the Constitution of the United States.”

Tracking down the judge

Judge Deborah Hedlund lives out of state now and is retired, but she remembered Townsend’s case. She agreed to read over some of the documents to refresh her recollection.

She said she had reservations about Jones’ testimony, and suspected that he and Townsend may have collaborated on the story.

But she still thinks she might have granted a new trial. That’s because she said prosecutors made a mistake during the trial. While they brought up Townsend’s criminal record, they never uncovered the fact that Jones had prior convictions as well. His record in Illinois included felony theft, battery and armed robbery. It also included an eerily similar home invasion where he later said under oath that he had intended to rape the woman.

Julie Jonas and the Innocence Project dug up those convictions when they took on Townsend’s case. But the jury in Townsend’s trial never heard about them.

At the 2007 hearing for a new trial, Hedlund asked the Hennepin County prosecutor about this. According to the transcript, he said it was a “regrettable circumstance” but that he didn’t believe it was enough to grant a new trial.

Hedlund said that’s still what “disturbs” her the most about Townsend’s case.

She said it’s a case that “sits on the edge of a knife.” But if there’s any doubt in this kind of situation, she said it goes in favor of the defendant. “It would have been interesting,” she said.

But of course, she never got the chance to make a ruling.

‘I’m always afraid’

Townsend is in his early 70s now, and has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a lung disease. He works as a janitor, and kept working through the COVID-19 pandemic, when many people had the luxury of staying home.

He wants to retire, but doesn’t have the money.

Minnesota court records show Sherman has not been convicted of a single crime since he was let out in 2007. But he said he still worries every time he hears about a burglary in Dinkytown.

“I’m always afraid, like they had this fool out here breaking into houses not too long ago,” he said. “And those kind of crimes bother me out here in southeast Minneapolis, because I always think, ‘Oh, well my name’s probably the first thing they’re gonna think of for something like that.’”

Townsend said police caught the most recent offender, which “took the burden off” his mind - for the time being.

“If they can convict me wrongly once, they can do it twice,” he said.