KARE 11 Investigates: Mentally ill and violent kids, unable to stand trial, let go

Gaps in Minnesota’s juvenile justice system allow violent kids found mentally incompetent to be sent back to the community with little or no treatment.

Sitting in her Richfield home alone, working on her computer one night last September, 77-year-old “Jean” suddenly heard a male voice behind her.

“Where’s your stash?” he demanded, before he repeatedly punched her on the right side of her head, according to a criminal charge.

“I could have died,” said Jean, who asked that only her middle name be used to protect her safety.

A few weeks later, Katie – who asked that her last name not be used – drove down a south Minneapolis street when the same male, accused of being with a group, tried to carjack her.

“I was traumatized. I was pretty scared,” she said.

When both women saw his face, their reaction was the same.

“I just said, 'Oh my god, he’s so young,'" Katie said.

“So young. So young,” said Jean.

He was only 16.

When they learned about the boy’s history, they got angry.

Two months before he was accused of attacking Jean and Katie, he was in the Hennepin Juvenile Detention Center facing numerous charges for his alleged involvement in other armed robberies.

Yet, after finding that he was incompetent to stand trial, a judge let him go – without treatment and little supervision.

“They let him go to commit more crimes – and he did,” Katie said. “And one of them was mine.”

The boy is what’s known in Minnesota as a “gap case,” where suspects charged with crimes fall through gaps in the state’s criminal justice and mental health systems.

Turned loose

Here’s how the teen fell through those gaps.

When a child charged with a crime is either too mentally ill or does not have the intellectual capacity to assist in their own defense, they are declared incompetent to stand trial and the case is suspended.

Then there are three options available to judges:

- Civil commitment for their mental illness – which rarely happens.

- The county can open a "child protection" case for the child, and work with their parents to provide services.

- Or they are simply released with little more than the hope they won’t re-offend.

That third option is used in three out of every four cases, a KARE 11 investigation has found.

'That is a danger'

KARE 11’s reporting on gap cases in the adult system last year led to the Minnesota legislature passing sweeping statewide reforms.

But lawmakers specifically excluded kids from those reforms.

A new KARE 11 investigation finds many of the same gap case failures still exist for juveniles:

- Since the law requires cases to be suspended – even when they involve violent crimes – judges can’t order juveniles to be held in detention or released under law enforcement supervision.

- Unless there is a rare civil commitment or child protection case, judges’ hands are also tied in these cases because they have no authority to order children to get treatment to restore them to competence.

- Even if they did have that power, there are no competency restoration programs in Minnesota tailored to juveniles.

As a result, juveniles found incompetent in Minnesota are routinely turned loose without treatment or supervision.

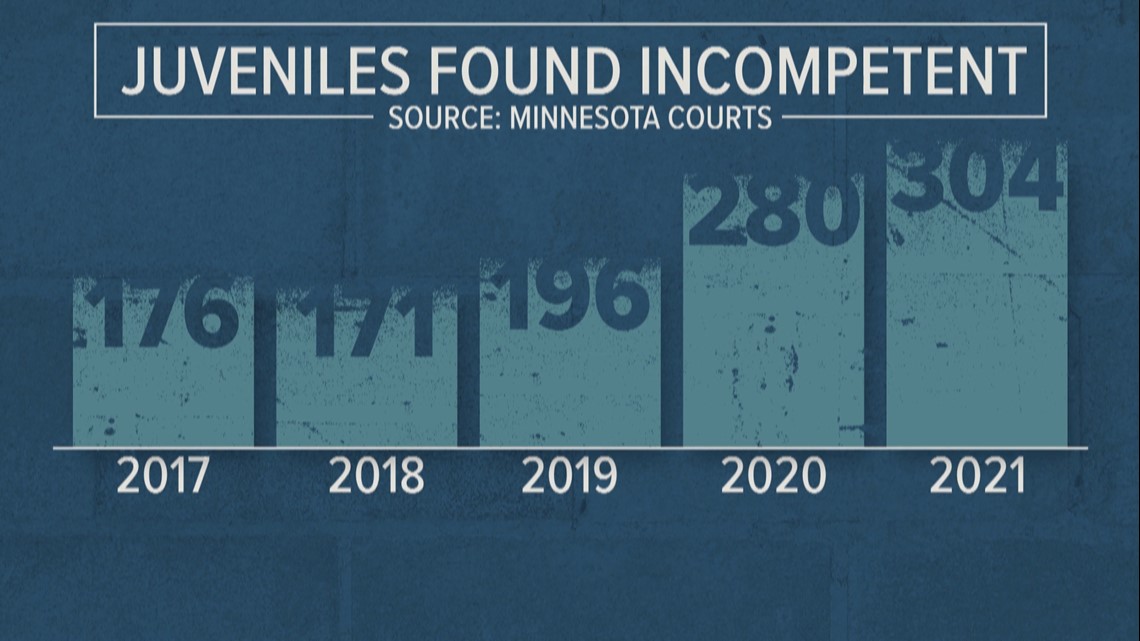

Those gaps remain even as Minnesota courts face a growing problem. The number of juvenile gap cases has nearly doubled in the last five years, according to data from the Minnesota Courts Administration.

Judge JaPaul Harris, who presides over Ramsey County Juvenile and Family Courts, said many kids unable to stand trial do not qualify for the options available to judges.

As a result, "anytime you have an untreated individual, whether it’s a youth or adult who has engaged in behavior, that is dangerous. That is a danger,” he said.

If legislators do address juvenile gap cases when they return to St. Paul next year, a closer look at the boy accused of attacking Jean and Katie could provide insights into how Minnesota fails mentally ill children and the public – and what could be done to fix them.

Better off abandoned?

When the boy was 4, his grandmother, Emma, took custody of him after she said his mother neglected him. KARE 11 is not using her last name in order to protect her grandson’s identity.

He needed mental health treatment dating back to elementary school, according to court records. Sometime around 7th or 8th grade, Emma said her grandson started acting out.

She took him to therapy for several years and got him medication, but he wouldn’t take them. He broke windows and put holes in the walls of their home. She worried that he was involved in gangs.

Emma, 79, said she felt powerless to help him – or stop him.

“He was out of control,” Emma said. “He’d run in and out the house like there was no door there.”

In January of last year, when her grandson was 15, he and another defendant were accused of beating a man and stealing his car. In April, he was accused of robbing a man at gunpoint who was waiting at a bus stop. The next month, he was with another suspect when he was accused of pointing a gun at a Lyft driver and then stealing his money and car.

After being charged that summer and held in juvenile detention, a court evaluation recommended that he be found not competent to stand trial for the charges.

Hennepin County Judge Mark Kappelhoff, who was presiding over the case, agreed and ruled him incompetent on July 6.

But that decision set the clock ticking for the boy.

State court rules mandate that unless juveniles found incompetent are committed for mental illness, or a child protection case is opened for them, then they must be released from detention within 72 hours.

Neither happened for the teen.

The county’s social workers wanted Emma to pick him up from detention, but she refused, saying she wouldn’t take him unless the county put treatment and supervision services in place.

Otherwise, she feared he would just leave her home and re-offend while putting his life in danger, she said in an interview with KARE 11.

“If he’s incompetent, where’s the help at? I can’t help him,” she said.

She said the county offered her nothing, so when it came time for her grandson to be released from detention, she didn’t show up.

After a week passed with the boy still being held in juvenile detention, Emma was told that if she didn’t pick him up, her grandson would be considered an abandoned child. If that happened, child protection workers would come to get him, according to court records.

Emma said she and her family reluctantly decided to go that route, believing that turning him over to child protection was the best way to help him and keep him off the streets.

In late July, a judge gave Hennepin County interim legal custody and control of Emma’s grandson, putting his well-being in the hands of social workers.

That only made his situation worse – for him and the public.

While under the care of the county, the boy was at times homeless, went missing, and was shot – all while accused of going on a violent crime spree.

'I was traumatized'

Records show the county took the boy to an unsecured treatment facility in Anoka. Less than a month later, he ran back to his grandmother.

Social workers met with the two that day, where they agreed the boy would stay with Emma as the county worked to get them mental health services. But records show there appeared to be no plan to address what to do if he again ran away.

“There’s no bad bone in his body,” the social worker said at the meeting, according to court records.

A month later, on Sept. 14, the boy is accused of breaking into Jean’s Richfield home along with an accomplice, robbing the elderly woman that night of not only money but any sense of safety.

“I’ve lived in Richfield for 42 years and always, always have I felt safe,” she said. “Until now.”

Meanwhile, staff from the boy’s school told county social workers that he had attended only one day of class that year, and when he was there, he slept through most of it and looked like he had been sleeping outside.

A judge issued a warrant for him, but a week later he was accused of robbing a school transportation driver at gunpoint.

Two days later he was shot in the calf. When it came time to discharge him from a hospital and send him to a shelter, none would take him. Some were full, while others rejected him because of his history of violence.

Social workers again appeared to lose track of him. In late October, he and a teen girl were accused of kidnapping a man at gunpoint, forcing him to get into a stolen car, drive to a south Minneapolis ATM and withdraw $900.

Two weeks later, he’s accused of being with another accomplice when they robbed a bodega near the University of Minnesota.

It would take an alert 76-year-old woman to help finally apprehend him.

On Nov. 15, that woman – Katie – was driving her van in south Minneapolis, when the boy and at least one other person were accused of pinning her with a stolen car they were driving.

Katie said in an interview with KARE 11 that she knew right away that she was being carjacked. The boys ran to her van and demanded she get out, but she locked her doors and laid on her horn.

“I was angry at that moment. I thought 'They’re not getting this car,’” she said.

Katie quickly called 911, allowing police to find them nearby.

Facing prison

The boy would spend the next several months at the Hennepin Juvenile Detention Center, where he was again found incompetent to stand trial in March, diagnosed with severe conduct disorder, ADHD, depression and anxiety disorder.

Following another competency evaluation in August, a judge deemed him able to stand trial. All told, the now 17-year-old faces eight felony cases. Hennepin County wants to try him as an adult. If convicted, he would face a presumptive prison sentence.

But neither Jean nor Katie want to see him go there.

Instead of anger toward him, both said they have only compassion for a boy who was so profoundly failed by the county’s court and mental health systems.

“I can’t stop tearing up from it. It’s so sad to think that he could’ve been saved,” said Katie.

Jean believes he can still be rehabilitated, but only with the treatment and supervision that he was never given.

“There needs to be more care for the young kids that are breaking laws,” she said. “So they can learn a better way of life.”

Watch more KARE 11 Investigates:

Watch all of the latest stories from our award-winning investigative team in our special YouTube playlist: