ELK RIVER, Minn — The red flags were there.

James Lynas told a nurse at the Sherburne County jail in 2016 that the pain in his stomach from drug withdrawal was so bad that he considered killing himself.

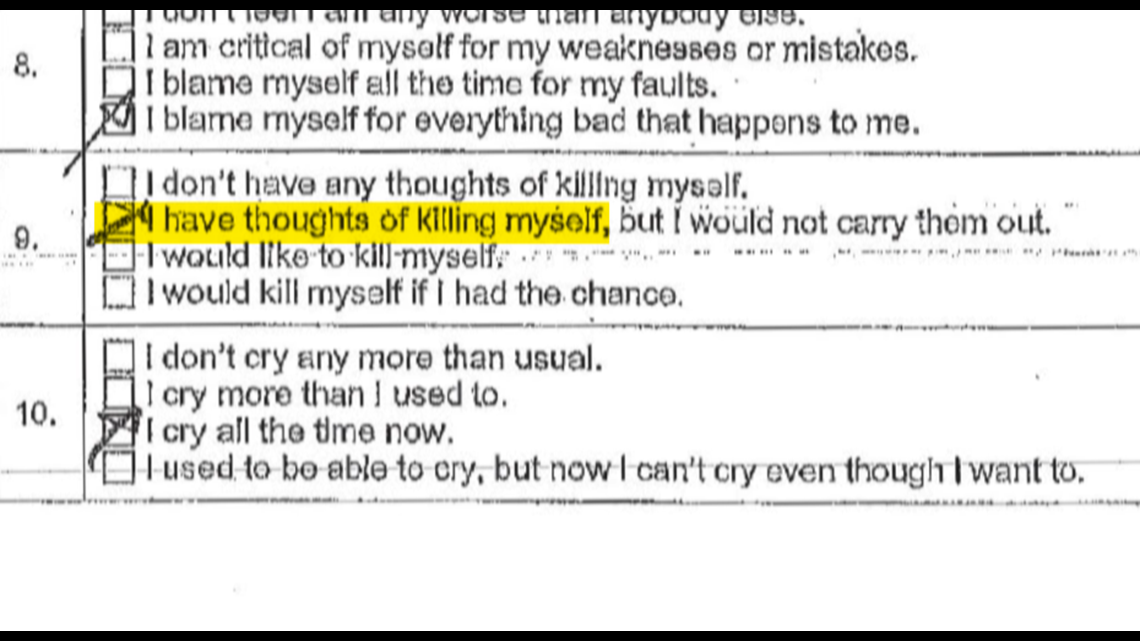

He told another nurse his mind was going crazy with thoughts, that his insomnia was maddening. “I’m suffering and I’m not coping with it,” he said. On a mental health self-evaluation, he marked a box that read “I have thoughts of killing myself, but would not carry them out.”

But the only treatment Lynas would receive at the jail was a prescription for an antihistamine that can be used to treat anxiety. He never saw a mental health professional.

Nine days after being booked for a DWI, he hanged himself with a bedsheet in his cell.

National guidelines say in death cases like that, his medical and mental health care should have been reviewed to determine if red flags were missed or ignored, and whether policies at the jail could be improved so that a tragedy like it never happens again.

“You do this review with an eye towards saying, ‘What are we going to do different to prevent this from happening in the future?’” said Dr. Kevin Fiscella, who sits on the board that developed the standards.

In the Lynas case, that review never happened.

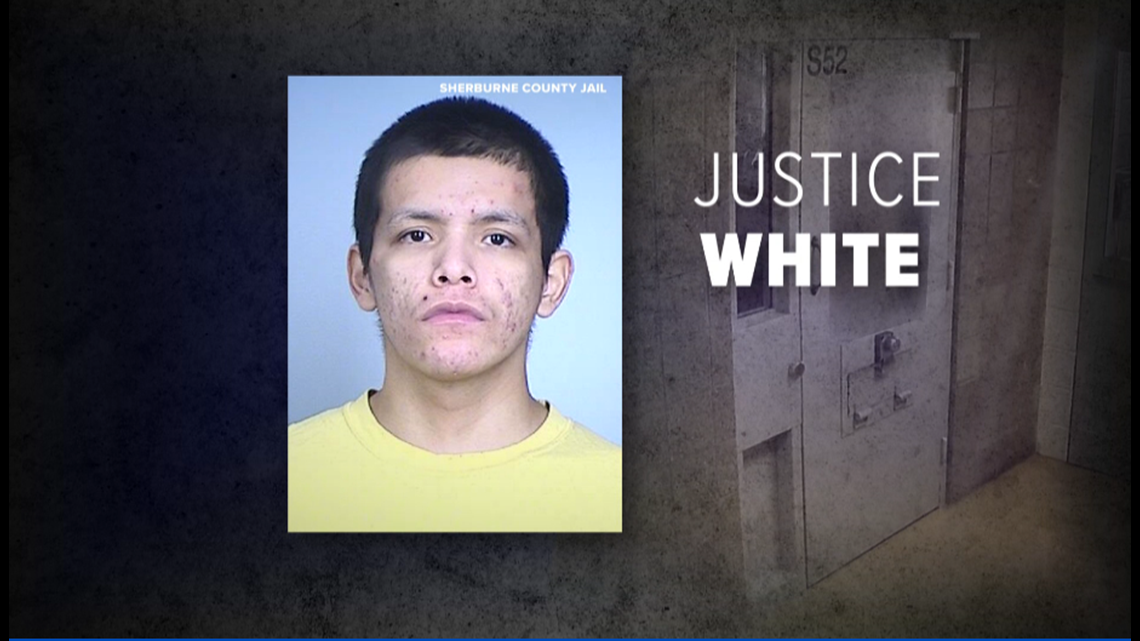

Two and a half years later, another Sherburne County inmate battling depression at the jail, Justice Lee White, killed himself in the exact same manner and same cell as Lynas.

Two examples among dozens that show despite years of alarms and inmates dying, counties across Minnesota and the state Department of Corrections (DOC) have ignored national guidelines for investigating deaths behind jail bars, KARE 11 Investigates has found.

Flawed investigations

Since 2015, 56 inmates have died in 30 Minnesota county jails which house defendants either awaiting trial or serving short sentences of less than a year.

A KARE 11 review of court, police, and medical records, along with interviews and surveys of every county where an inmate has died shows:

Of the counties that responded to our surveys, only Hennepin, Ramsey and Anoka said they follow the best practice standards for reviewing a jail death.

Suicides accounted for more than half of the inmate deaths. But outside of those three metro counties, KARE 11 could not find a single case where the inmate’s mental health care was reviewed by a mental health professional as national standards recommend.

The state legislature and DOC were warned about the lack of medical and mental health reviews in a 2016 report by the Legislative Auditor – but failed to make the suggested changes to correct the problems and save future lives.

Perhaps most troubling is that the one person responsible for the health care of more Minnesota inmates than any other does not follow the national standards.

Nearly half of the inmate deaths since 2015 have happened under the watch of MEnD Correctional Care, a Sartell-based for-profit company that provides health care to a third of the state’s jails, according to court and county records.

Yet MEnD’s owner, Dr. Todd Leonard, who supervises all of the health care the company provides, said during a sworn deposition last year that he couldn’t name a single review he’d written after an inmate under his company’s care died.

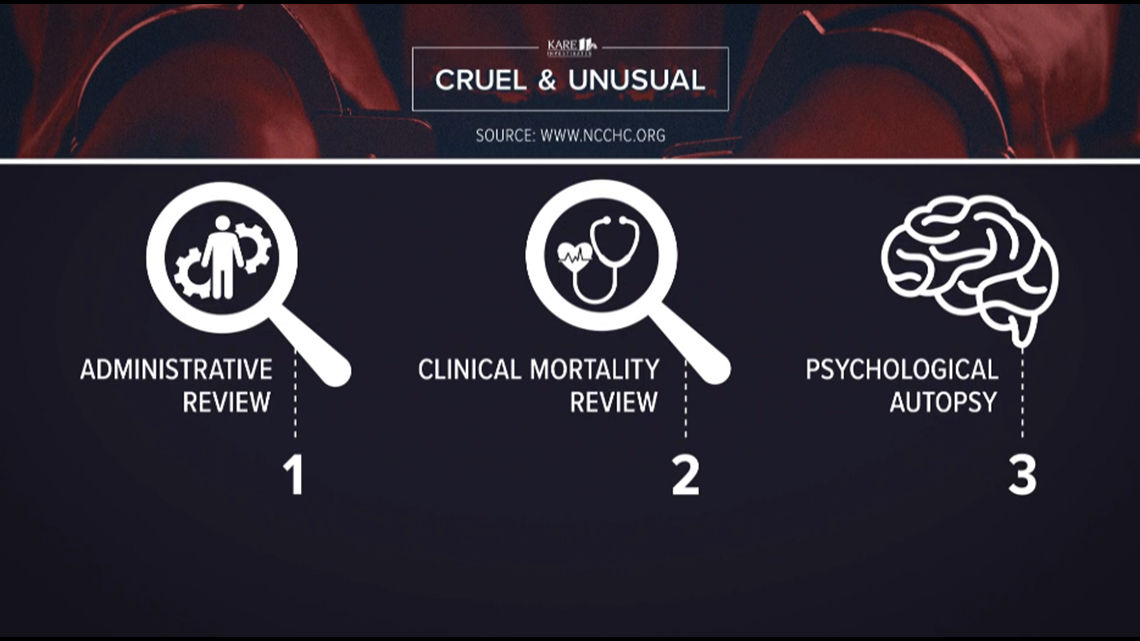

That is the opposite of the standards promoted by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, which recommends three types of reviews following an inmate’s death in order to help prevent future tragedies:

- An Administrative Review – to see where jail policies and procedures can be improved.

- A Clinical Mortality Review – to assess whether medical and mental health care could have been better provided.

- A Psychological Autopsy for suicides – to focus on the mental health factors that contributed to the death.

The last two reviews are supposed to be done by professionals not involved in the inmate’s care.

“It would be like auditing your own taxes,” said Dr. Brent Gibson, the NCCHC’s chief health officer.

Yet Leonard said during the deposition that he reviews the deaths under his watch.

“I review each case on its own merits,” Leonard said. “And if there is a substantive concern of mine, then I would report that to the jail administration.”

He said If he sees a problem with MEnD’s care, “then I will delineate that and we will put in place whatever we need to put in place to make those changes.”

In the Lynas case, Leonard said he “did not find substantive changes that needed to be made in the way care was handled.”

In other deaths under MEnD’s watch, Leonard said during the deposition that there were “things where I felt we could tweak or fine tune.” But when pressed if he ever put one of his reviews in writing, he responded, “I can’t name one.”

Leonard declined to comment to KARE 11 on the Lynas case because of pending litigation, but in a statement the company has defended the overall care provided to inmates, saying “we have provided quality medical care to thousands of individuals in correctional facilities across the upper Midwest. Over this time, we feel that we have made a tremendously positive impact on our individual patients, and our industry as a whole.”

Previous failures unaddressed

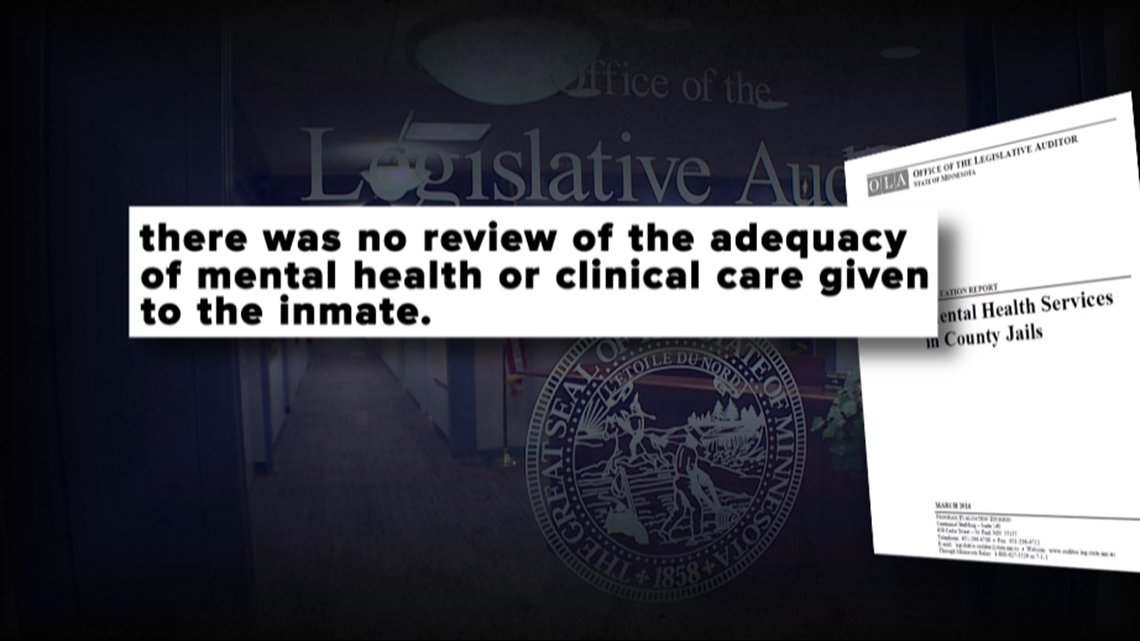

As Minnesota jail populations have swelled with the mentally ill, a 2016 Legislative Auditor report found that for years counties had persistent problems providing them with mental health care.

That audit found the DOC, which licenses jails, failed to collect reliable data on inmates with mental illness and that the state failed to follow professional standards for investigating suicides. It concluded “there was no review of the adequacy of mental health or clinical care given to the inmate.”

Since then, state leadership has done little to respond to those findings. No major laws were passed, or policies changed, KARE 11 has found.

Although the DOC conducts mortality reviews after deaths in state prisons, it only examines administrative failures in county jail deaths, such as whether appropriate well-being checks were conducted on time and properly logged.

Even those investigations are often flawed, or toothless, KARE 11 has previously reported.

A review of each of the 56 jail inmate deaths since 2015 found that the state regularly missed or dismissed critical evidence which indicated that deaths could have been prevented.

The state never used its authority in any of those deaths to restrict a county’s jail’s license and limit the number of inmates a jail can hold.

The director of the state’s jail Inspections and Enforcement Unit has since stepped down in the face of an internal DOC investigation into the policies and procedures of the team he led.

In the Lynas case, the DOC found the jail committed no administrative violations.

But a lawsuit filed by Lynas’ family exposed what a federal judge would later say was clear evidence Lynas had a serious medical need.

In an August order refusing to dismiss the lawsuit, Judge John Tunheim ruled that a reasonable jury could find that Sherburne County and MEnD were “deliberately indifferent” to the safety of suicidal inmates.

“Urgent” mental health referral

Lynas was the kind of guy with a big heart who would give you the shirt off his back, his sister Charity Brown remembers.

“He would do anything to make anybody happy,” she said

He also had his demons. He became addicted to painkillers and seemed to suffer from depression after an accident left his face disfigured in 2016. That’s when Brown suspects he began self-medicating with other drugs.

After being booked into jail, his withdrawal from opioids was severe, causing tremors, cold sweats and severe pain, according to medical records.

A nurse wrote in his chart that he told her he was “definitely feeling depressed,” and that “his insomnia is maddening, his mind is going crazy with thoughts.”

After a mental health screening indicated he had “severe depression” on November 5, a physician’s assistant prescribed an anti-anxiety drug, placed him on a suicide watch and ordered what she called an “urgent mental health referral” with a MEnD psychologist.

Despite that urgent request, records show the mental health appointment was scheduled for November 16th – 11 days later.

Lynas died before he was seen by a mental health expert.

“I continuously asked him is anybody helping you? And he continuously told me, ‘Nobody is helping me. I’m not getting any kind of care for anything,’” said his sister.

The MEnD psychologist who was scheduled to see him later wrote, “it was never a case I was involved in.”

Flawed suicide watch?

Lynas was placed on a mental health watch, where guards were supposed to observe him every 15 minutes.

But in the Sherburne County jail those watches were severely flawed.

Guards testified in depositions that they often conducted their checks from a catwalk where they could only see into a part of his cell.

When Lynas hanged himself, he moved to a part of the cell the guards could not clearly see.

“It’s likely that he was hanging himself during one of his checks,” said Robert Bennett, the attorney representing the Lynas family.

In his recent ruling, Judge Tunheim wrote that the guard’s checks that morning “amounted to no checks at all.”

Despite the limited view of the cell, the original investigation conducted by the state Department of Corrections found that nothing went wrong in the case.

That finding is now being reviewed. Corrections Commissioner Paul Schnell announced in July the state is re-investigating all jail deaths since 2015.

The decision to review those cases came after a mother’s public protests led DOC to admit it botched a similar investigation of an inmate death in Beltrami County that also involved MEnD and allegations of denied care.

“Did not follow this to the letter”

MEnD and Sherburne County have defended their care of Lynas in court filings, saying that while he said he had considered suicide, he also told a nurse he wouldn’t go through with it because he wanted to put his life back together for his daughter.

“He expressed no sense of urgency,” MEnD’s attorney argued in a motion to have the case dismissed.

During one deposition, Leonard acknowledged Lynas was never seen by a qualified mental health professional.

He also acknowledged that MEnD did not do a mortality review or psychological autopsy as recommended by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. He testified that was because the jail had not been accredited by group at that time.

“We did not follow this to the letter of this standard,” he said.

State acknowledges failures

Yet Lynas wasn’t the first to commit suicide at the Sherburne County jail under the county and MEnD’s watch.

In Oct. 2017, a month before Lynas died, Dylan Brenner, also hanged himself.

Then in April of this year, Justice Lee White, an inmate waiting trial for sexual assault charges, also committed suicide.

White had tried to kill himself only four months before and was undergoing treatment for mental illness. Two months later, White was put in an anti-suicide gown after an inmate wrote to a guard that White “needed to be watched closer,” according to sheriff’s records.

Yet White was released from the anti-suicide gown requirements and on April 10 was placed in the same cell where Lynas had been held. Just as Lynas did two years before, he tied a bedsheet to a grate on one of the walls, made a noose and hanged himself.

Possible changes coming

When questioned by KARE 11, the Minnesota DOC acknowledged that professional standards are not followed when investigating jail deaths.

“That said, Commissioner [Paul] Schnell is interested in the possibility of clinical mortality reviews for jail deaths. He has had conversations with some sheriffs about it and is exploring what that might look like and how it could be implemented,” said DOC spokesman Nicholas Kimball.

The Minnesota Sheriffs’ Association supports adhering to policies that call for the national standard reviews, said Executive Director Bill Hutton. But he also acknowledged that those reviews were likely not always being done.

Some counties appear to be changing.

After a KARE 11 inquiry, Scott County Sheriff Luke Hennen said they will review their policies and “will be updating them to better reflect national standards and follow the same guidance as DOC uses in their facilities.”

And Dakota County told KARE 11 they are reviewing their policies to ensure they are thorough and in line with established standards and best practices.

However, at least one county said while it adheres to the standards, they haven’t actually done all of the reviews.

“Our facility has conducted Administrative Reviews and Clinic Care Reviews after our inmate in-custody deaths,” wrote Commander Roger Heinen, the Jail Administrator for the Washington County Sheriff’s Office in an email to KARE 11.

However, he added, “We have never conducted a Psychological Autopsy.”

The Washington County jail has had two deaths by suicide since 2017.

If you have a tip about something KARE 11 should investigate, contact us at: investigations@kare11.com