ST PAUL, Minn. — In February, it seemed a foregone conclusion.

In the wake of a series of KARE 11 investigations, Minnesota lawmakers were set to push through sweeping reform to require testing of all rape kits in cases where the victim reported the crime to police.

The agency that would do the testing – the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) – estimated the cost would be $7.2 million over the next three years should the bill pass.

Then came the coronavirus crisis.

That $7.2 million price tag has led some lawmakers to question whether the state can afford to move forward with the plan since the state now faces a multi-billion- dollar deficit.

Even the Minnesota Coalition Against Sexual Assault (MNCASA) is backing off on their calls for mandatory testing in light of COVID-19 and is seeking a scaled down version of the current proposal.

However, a new KARE 11 investigation finds the BCA appears to be wildly overestimating the cost of the proposed legislation.

While BCA leaders have publicly said they support the bill, an advocate with the nation’s largest anti-sexual assault organization suggested efforts could be underway behind the scenes to kill the bill by inflating its costs.

“Sometimes state agencies will tack on an excessive fiscal note as a way to kill the bill,” said Camille Cooper, Vice President of Public Policy for the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). “It’s a known legislative tactic.”

Multi-million-dollar price tag

The reform bill was introduced after KARE 11 revealed widespread failures across Minnesota to properly test rape kits. In a series of reports, KARE 11 documented how potentially thousands of cases were never fully tested, kits were destroyed without testing, and victims are often left in the dark as to the status of their kits.

The BCA prepared a “fiscal note” for the legislature – an estimate of the costs should a bill pass. The agency concluded that about 97 percent of assault cases would come with sexual assault kits to test. That would more than double the number of kits needing to be tested to about 2,700 a year.

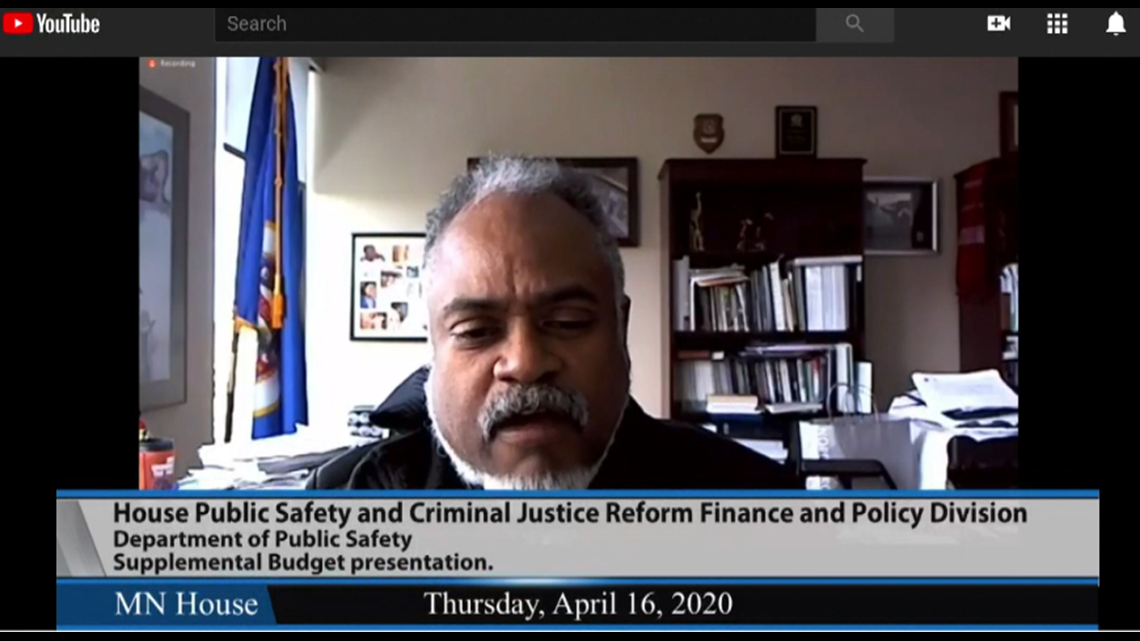

In a recent House legislative hearing, Public Safety Commissioner John Harrington, who oversees the BCA, explained the cost of the proposal. He said it would also include creating an online tracking system to allow victims to look up the status of their kit, and the storage of rape kits done at hospitals where the victim has not yet reported to police.

“Our request for this proposal is for a total of $3,096,000 in fiscal year ‘21,” Harrington said, adding, “and then there is a $2,067,000 ongoing request thereafter.”

The BCA said much of the money would be used to hire new forensic scientists and purchase additional lab equipment needed to test the additional 1,500 rape kits the agency estimated they’d get each year – and then load the results into the state and federal DNA databases.

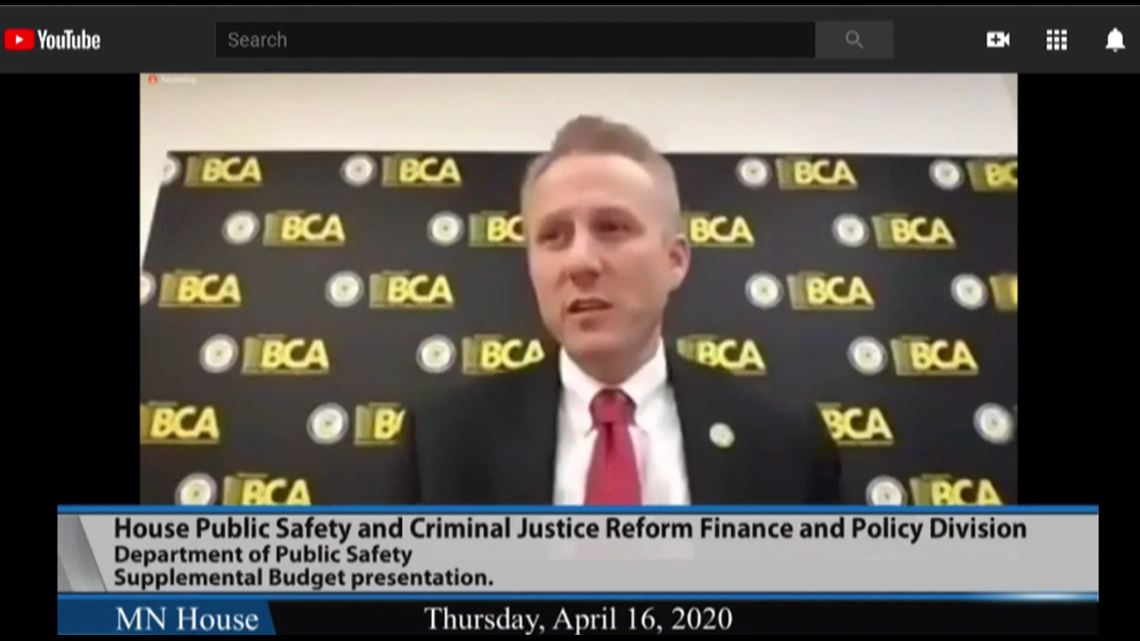

“How many employees are you looking at adding for that?” asked Rep. Paul Novotny (R- Elk River) during the hearing.

“It’s eight scientists for DNA, and I believe two for the tracking portion which are technicians,” replied BCA Superintendent Drew Evans.

However, KARE 11’s investigation raises serious questions about the accuracy of the BCA’s estimates.

Bad Math

According to the fiscal note, the BCA came up with its estimates by comparing the number of rapes reported statewide to the FBI in 2019 to the number of kits they had tested.

There were 2,763 reported rapes, but only about 1,200 kits were tested.

So, the BCA assumed “they would receive an additional 1,500 cases for testing per year.”

The fiscal note states: “With this bill, all kits would be required to be submitted which would include the vast majority of reported rape cases.”

But that’s not realistic said Cooper of RAINN.

“What was your number one takeaway after looking at the fiscal note?” asked investigative reporter A.J. Lagoe.

“I didn’t think they did the math right!” exclaimed Cooper.

“It’s never going to be one to one,” she said. “You’re never going to have the number of rapes that are reported … be the same exact number as the number of rape kits that are performed.”

Simply put, kits are not done for every rape that is reported.

Cooper said the main reason is that rape kit forensic exams need to be done within five days of the assault and many victims wait weeks, months, and even years before reporting their rape.

“Those numbers are never going to match,” she said.

After the BCA released its projections, KARE 11 asked the agency in February how it concluded that the vast majority of rapes came with a kit.

The BCA never directly responded to the question. Instead, BCA spokeswoman Jill Oliveira said in an email that “there was no way” for the agency to determine how many kits would need to be tested.

The Survey

KARE 11 found a simple way to get a better estimate.

KARE 11 surveyed two dozen of the police agencies that had reported the highest number of rapes according to the crime statistics compiled by the BCA each year and posted on the Department of Public Safety website.

We asked them to tell us how many rapes had been reported to their departments and how many kits had been collected.

The results showed less than half of the sexual assault cases came with kits.

Saint Paul, for example, reported having taken 513 reports of rape combined in 2018 and 2019 for which there were 349 corresponding kits.

Rochester reported 209 rapes with just 65 sexual assault kits.

Duluth had 82 reported rapes with 31 sexual assault kits. Why such a big difference? Duluth provided additional data showing the main reason was delayed reporting – the same issue Cooper of RAINN had identified.

All told, 18 of the 24 cities KARE 11 surveyed responded in time for publication. In all, the survey revealed there were 1590 reported rapes, but only 770 rape kits.

The results show less than 50 percent of reported rapes in Minnesota during the last two years resulted in the victim having a rape kit exam performed. Far less than the “vast majority” the BCA’s budget estimate had assumed.

KARE 11’s survey suggests that if the “test all” bill passes, the BCA is likely to see about 150 additional rape kits that need to be tested each year, not 1,500.

If so, fewer new scientists and lab equipment would be needed.

“They’re trying to make some pretty impactful reforms there in Minnesota,” said Cooper. “And one of the surest ways to kill a bill is to tack on a really high fiscal note.”

KARE 11 requested interviews with both BCA Superintendent Drew Evans and Public Safety Commissioner John Harrington. The Commissioner’s office never responded. The BCA declined an interview through a spokesperson, but sent a statement saying, “The BCA continues to support the proposed legislation.”

If you have a suggestion, or want to blow the whistle on government fraud, waste, or corruption, email us at:

investigations@kare11.com