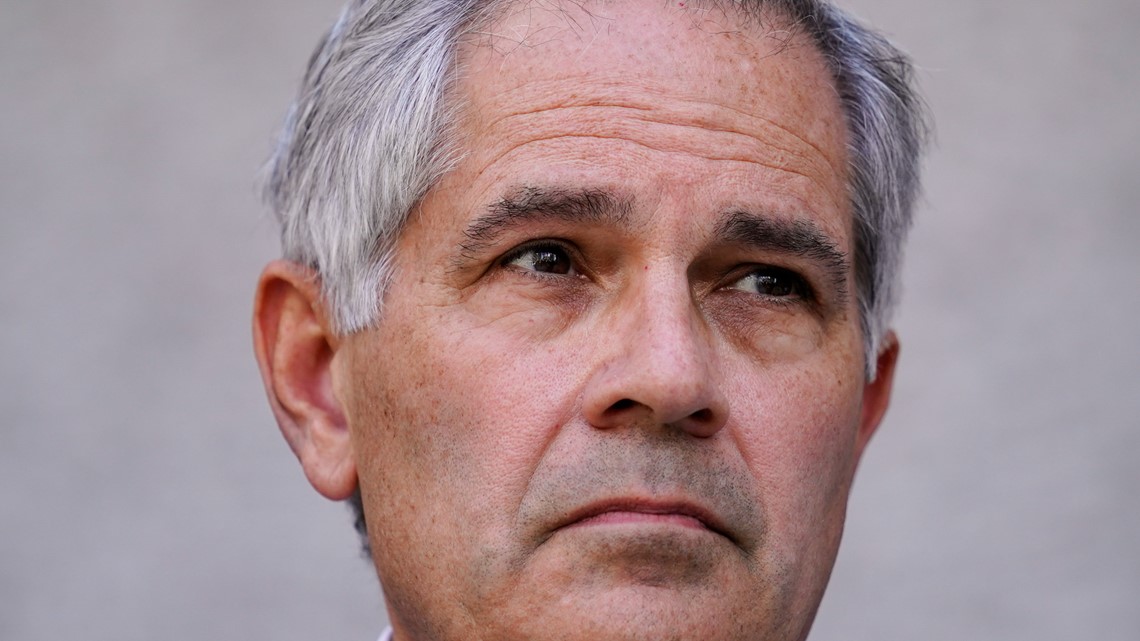

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner took issue with a question he was asked at a recent press conference.

“Everybody in prosecution has looked at ‘What's your win rate, what's your win percentage, what's your batting average? What's your conviction rate?’” Krasner said. “No one ever really said, ‘What is your accurate conviction rate?’ They just said, ‘What is your conviction rate?’”

And this key metric of success has actually gone down since Krasner started doing what he set out to do: reverse convictions.

Krasner’s office operates something called the Philadelphia Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU), with the purpose of re-examining convictions won by prosecutors in his jurisdiction. When they find one that doesn’t hold up, they go to a judge and ask for it to be overturned.

While these units have become more and more popular across the country in recent years, Philadelphia’s is especially aggressive. The unit has achieved 21 exonerations for 20 people since Krasner took office in 2018.

“One of the things we realized is that we were lowering our batting average, we were lowering our conviction rate,” Krasner said. “We were looking worse for having the system do the right thing. You know, the metrics of injustice are built into, even built into how we talk about it.”

Bringing in an outsider

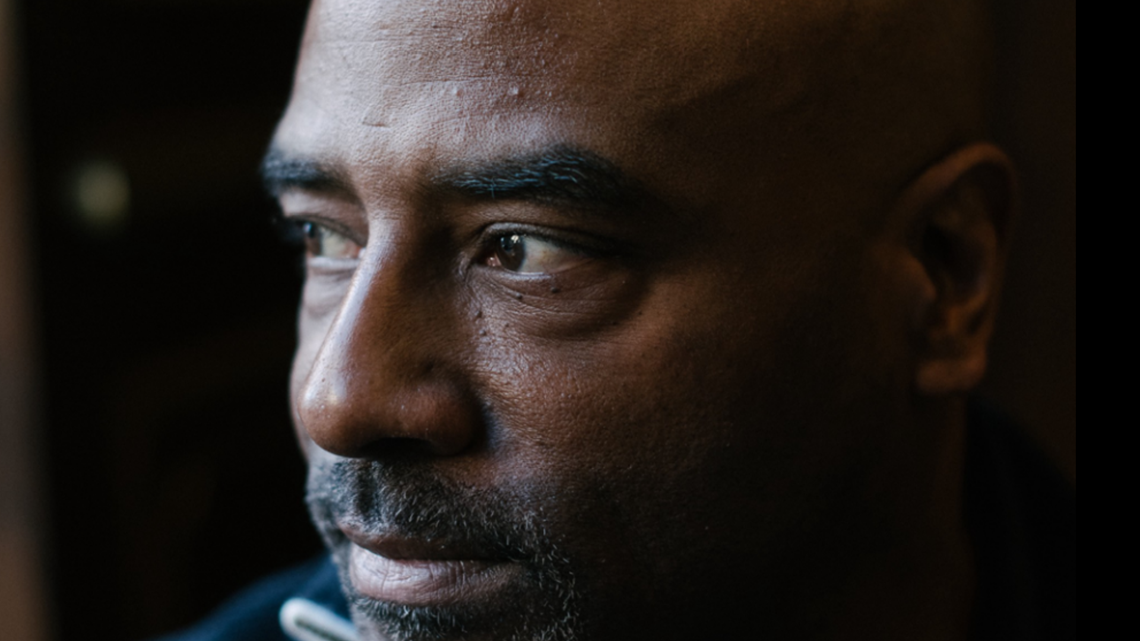

Shortly after taking office, Krasner brought in Patricia Cummings to lead the CIU. Cummings came to Philadelphia from Texas, and said it’s been tough at times to assume that role.

“More than one occasion I had people in the criminal justice system say to me, ‘I'm not going to let this girl from Texas tell me how to do things in Philly,’” she recalled.

But Krasner brought in an outsider on purpose.

RELATED: New research shows prosecutors often fight winning innocence claims, offer deals to keep convictions

“One of the biggest pros that you have in bringing an outsider in is that you don't have that kind of proverbial ‘the fox guarding the henhouse,’ because I don't have alliances to prosecutors or defense lawyers or to judges,” Cummings said. “I really am coming in and saying, ‘I am going to look at this as objectively as I can and ultimately make recommendations regarding what I think is right.’”

Krasner said even when the CIU is looking at a case from 20 years ago, there can still be people in the DA’s office with a close connection.

“The same prosecutor may be in the office,” he said. “The mentee of that prosecutor may be in the office. And people who have been here for some time often view it as an attack and a reproach that you're looking over their shoulder, especially if you determine that we should try to undo a conviction.”

Krasner said this process can cause discomfort in the office even among “people of goodwill.”

“There can be people in the office who were not tied up with the mistakes of the past, the misconduct of the past, the crimes committed by prosecutors in the past, but who nonetheless kind of bridle at the independence,” Krasner said. “Want to view themselves as being part of the team, having access to all the same information, pushing for the same just outcomes, wanting consensus.”

While Krasner can acknowledge the tension that arises in an organization trying to correct past mistakes, he said he does not think there should be any disagreement on the overarching goal.

“I see no tension in the notion that a prosecutor should be trying to do the right thing moving forward, and trying to do the right thing moving backward, even if that means fixing past misconduct or mistakes or, frankly, prosecutorial crimes,” Krasner said.

In fact, Krasner and Cummings are both adamant that it is the prosecutor’s duty to fix the mistakes of the past. It’s even written into the prosecutor’s ethical obligations in the model rules recommended by the American Bar Association.

“Three-point-eight of the model rules says that prosecutors do have an obligation to disclose exculpatory information in a post-conviction setting,” Cummings said. “And they do have an obligation, if they've received evidence that maybe an innocent person has been convicted, they've got an obligation to do something about it.”

But Cummings said not every state has adopted those rules. She thinks they should.

“If I had my way, that would be the first step toward uniformity, toward making our criminal justice system much more reliable and fair,” she said.

The system is difficult for those seeking an exoneration - and Cummings said that’s on purpose.

“It's too difficult and it was designed to be too difficult, and that's just what our criminal justice system has been,” Cummings said. “And more specifically, we designed it for finality. And it goes back to the arrogance, I think, of the stakeholders involved in the system, and that is believing that we are getting it right. And so since we're getting it right, how dare anybody have the tools necessary to go back and open it up to see if, in fact, we did?”

As Krasner sees it, the criminal justice system “makes a god of finality.” Somewhere further down the line, he said, is justice.

‘A wartime field hospital’

Philadelphia is viewed widely as a leader in the world of conviction integrity units. While the National Registry of Exonerations lists 85 similar units across the U.S., 49 of them have not recorded a single exoneration.

But Philadelphia’s success comes at a high price when it comes to time, resources and money.

Cummings said her unit employs about 20 people including paralegals and lawyers - and even that is not enough.

“I was telling somebody the other day, our queue of cases to look at is so incredibly long that if all of us worked every day, we probably wouldn't get through that queue,” she said. “If you were really looking at them and not having to triage them the way we do, it’d probably take a decade.”

Cumming said in her unit, a whole team generally looks at each case.

“We want to make sure that we're having more than one set of eyes on the case because we recognize if you're going to step foot in a courtroom and ask for a conviction to be vacated or set aside, you'd better be darn confident in what you're asking the court to do,” she said.

The sheer number of likely wrongful convictions that are still left to be discovered leaves Krasner with a sense of urgency.

“The best that we can do to be honest about this, is view it as an emergency ward or maybe as a wartime field hospital,” Krasner said. “Where everything you're doing is triage. You have limited resources, you have limited time. People have been in jail cells for a very, very long time. And you're trying to figure out the ones where there's a possibility of saving a life and then you're trying to save that life.”

Prosecuting prosecutors

As Cummings and her team open old cases and find them to be lacking, they’re identifying recurring themes. Problems with eyewitness identification. False confessions. And prosecutorial misconduct that Cummings said can range from something unintentional, to negligence, to what looks more like a pattern.

“How can it be that sometimes folks can't recognize that maybe an innocent person was convicted and even go beyond that, do something about it?” Cummings asked. “And I don't think that it's always nefarious reasons.”

Cummings believes there’s often an intensely human trait to blame: cognitive bias.

“I guarantee you, prosecutors generally are going into it saying, ‘I want to do the right thing here and I want to convict a guilty person,’” Cummings said. “I don't think they're saying, ‘I want to convict an innocent person.’”

Patricia said at every turn, that prosecutor may have their belief in a person’s guilt affirmed. A police officer says the person is guilty. The prosecutor brings it to a jury, and 12 people agree. Then the case may go through years of appeals, where appellate judges agree, “You’ve got the right person.”

“And then all of the sudden something comes to light that kind of upsets that entire world,” Cummings said. “And it is so difficult I think, as human beings, for us to be able to step back and say, ‘Oh my God, we were all wrong.’”

Krasner does not disagree with Cummings, but he said he thinks this viewpoint is “a little nice.”

“I'll now say the terrible thing that's true, which is, some of these prosecutors belong in a jail cell,” Krasner said. “And they belong in a jail cell because when you look at what they actually did, it is evident that they were way more concerned about winning than they were concerned about whether or not an individual was innocent.”

Krasner said he has heard people in the Philadelphia DA’s office say things like “they must be separated from society,” when speaking about a single person. “So who exactly are ‘they’?” Krasner asked.

“I've heard prosecutors say, well, if he didn't do this, he did something else, as if that's an answer to a discussion about innocence for a particular charge, especially on a serious case,” Krasner continued.

Some people who have held positions as state-appointed prosecutors, Krasner believes, were “effectively criminal kidnappers.” Maybe, he said, if they sought the death penalty they should be considered “desk murderers.”

“We occasionally see that this is more than dumb lawyering,” Krasner said. “This is more than a culture. This is deliberate, willful, malicious, intentional effort to win at all costs without regard for the very obvious and significant possibility of innocence.”

The remedies available in these cases, Krasner said, are “seldom used in the United States.”

They can include sanctions from the bar association, efforts to revoke someone’s law license, and can even “theoretically” escalate to the point of criminal prosecution.

“Sadly both in the civil and in the criminal context, the worst of the worst prosecutors, for the most part, historically, have completely gotten away with it and have advanced their careers off of a win record that was built on cheating and on stepping on other people's lives,” Krasner said. “That's something that I would certainly like to see change.”

What is Krasner planning to do about the worst cases he’s seen?

“Stay tuned,” he said.