In 2003, a man was brought in for questioning by agents from the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA).

His name was Dale Todd, and he had been in this situation before.

He and two friends had been questioned in 1979, after Jeffrey Hammill was found dead by the side of Highway 12. Dale, Terry Olson, and Ron Michaels had given Jeff a ride that night, making them some of the last people to see him before he died.

Dozens of people were interviewed back then, and law enforcement scoured the scene in rural Wright County, Minnesota.

No physical evidence could be found. The manner of death was ruled “undetermined,” and the investigation “inconclusive.” The case went cold. Until nearly 25 years later, when Jeff Hammill’s biological daughter turned up.

“What got the ball rolling was the confluence of some circumstances,” said David Schultz, a Magistrate Judge for the District of Minnesota. He used to be an attorney, and at one point during this years-long case he represented Terry Olson.

“You’ve got a young girl who is searching for her biological parents and learns that her father, quote, ‘died in an accident,’” Schultz said. “Goes into the county sheriff's office in Wright County, where she encounters a fairly newly elected sheriff who had been in the department for a long time, and, you know, it piqued his curiosity."

Schultz said this all happened at a time when there was corporate funding available to help departments investigate cold cases.

Wright County Chief Deputy Joe Hagerty reopened the case, and the BCA came in to help with their “spotlight on crime” cold case initiative.

And that’s how they ended up in an interview room with Dale Todd nearly a quarter-century after Jeff Hammill’s death.

The interview

Dale had mental health issues and later said in a signed affidavit that he was addicted to painkillers at the time of his interview in 2003. He told the agents 30 minutes into the questioning that he was off his usual medication because he couldn’t afford it. Twice later on in the interview, he referenced previous nervous breakdowns.

KARE 11 obtained a video recording of the interview through a public records request.

For hours, Dale told the agents that he, Terry and Ron had nothing to do with Jeffrey Hammill’s death. But the agents didn’t believe him. They suggested that maybe Dale, Terry and Ron were drunk and stoned - and did something to Jeff.

“I never touched the guy,” Dale said at first. “I was not that drunk or… I would have known if I was hurting somebody. No, I didn’t touch Jeff.”

The agents told Dale that witnesses saw a car similar to his on Highway 12 that night. That was true. They also told him blood and hair were found on a bat in his car. They said they were going to test it and find out if it was Jeff’s. That was not true.

Dale kept saying he was scared. About two hours into the interview tape, he said, “I’m thinking that I’m being trapped into something that I didn’t do.”

One of the agents told Dale that when he’s telling the truth he speaks fluidly, but when things get foggy he bounces around. The agent asked Dale why he thought that was.

“Because I don’t think I was there,” Todd said.

The agent replied, “Another reason is you’re not telling the truth.”

The agents told Todd that even if he blacked out, they’re sure he remembers bits and pieces.

“There’s got to be some remembrance of something that happened,” they said. “We’ve given you the facts as we know them.”

Just short of three hours into the interview, Todd said he needed a cigarette and walked out. The agents followed him. There was at least a seven-minute break where the agents may or may not have been talking to Todd, off camera. The video shows only an empty interview room.

Dale came back in, and something had changed. He said he was starting to see pictures from that night.

“I’m getting these little pictures in my head,” he said. “And I think it was, it was Terry. I remember, I remember puking. For some reason puking comes into my head.”

There was no puke found at the scene, so what Dale was saying didn’t line up with the investigation.

He was crying. He said he thought they hit a deer, but now he was thinking it could have been Jeff Hammill.

The agents said, “I think we’re pretty sure that Jeffrey was not struck by a vehicle. I mean, at least, real hard.”

Dale got closer to implicating Terry and Ron, but still couldn’t remember Jeff being there. He kept answering their questions with “I think so.” He finally whispered, “I want to be sure.”

“Tell us what you think is sure and we’ll work with that,” the agents said. “Tell us what you think happened and we’ll work with the details.”

At one point Dale told the agents, “I could just say what you want me to say - it was Terry and him.” He was talking about Ron, whose name he kept forgetting. “But I don’t think that’s justice.”

The agents assured him they did not want that.

Four hours in, the BCA agents repeatedly asked Dale, “Who killed Jeff Hammill?”

Dale finally pointed to a picture of Ron.

“Who helped kill Jeff Hammill?” the agents asked.

“Terry?” Dale mumbled.

“I think it was him and Terry,” he said, crying.

‘Science will take over now’

Hours into the interview, Dale said he was getting more bits and pieces of that night.

“I, I see Terry hitting somebody and this guy here had something in his hand,” he said, referring to Ron again. He said when the two men came back to the car, Terry told him they had just beaten up Jeff.

Dale told the agents that in his mind and his heart, he knew he had nothing to do with Jeff’s beating.

“But in your mind you know who is responsible for Jeff Hammill’s death?” they asked.

“In my mind, I’m thinking Terry and Ron,” Dale said.

The agents kept trying to get him away from saying “I think so.”

“Is there any doubt as to the location where this happened?” the agents asked him.

“There was a little bit of doubt in my mind, yes,” Dale said. “Can I be absolutely sure? No, I cannot be absolutely sure.”

Dale started musing: If these two did do it, why didn’t he stop them? And why didn’t they hurt him? As he left the interview he said, “Science will take over now. Forensics. I watch the show all the time and it’s amazing what they can do.”

Dale now believed there was blood and hair on a bat, and that authorities could test it to crack the case. But there was no physical evidence.

As Dale got up to leave, he started talking about his mental health struggles again.

“I think I better go see a shrink or something,” he said.

“That might not be a bad idea,” the agents replied.

“Because I’ve been on these pills for quite a long time,” Dale continued. “And I’m off them now and I can start really feeling the stress.”

Dale’s wife called him then, and he answered in front of the agents - and on camera. He said he thought he should go see a “shrink.” And then he told her, if these are the guys who did it, the authorities might “throw something” at him - because he was there.

Dale still seemed to be waiting for the agents to figure out whether Terry and Ron did it. He didn’t realize that this interview would be considered a confession - and would form the basis of the entire case against all three men.

Building the case

Dale’s comments about puking by the roadside were puzzling, because nothing like that was found at the scene. Jim Powers was the Wright County chief deputy back in 1979, and he was one of the first people to arrive when Hammill’s body was found.

“It must have been 3 o’clock in the morning, somewhere around there,” he recalled. “We searched 100 yards each side of that location looking for any kind of weaponry, any kind of indication a vehicle stopped, any kind of footprints, anything of that nature, and we found nothing.”

There were other things Jim Powers found strange. There was no indication that Jeff Hammill ran, or was fighting anybody off. Jim said it looked like Jeff died quickly - no blood on his shirt. And no blood on his hands, indicating he didn’t hold them up to cover any of his wounds.

Jim Powers said he and the sheriff at that time believed it was a hit-and-run with a vehicle trailing a large piece of equipment.

David Schultz, who ended up representing Terry, said the Dale Todd confession looks different in hindsight than it might have in 2003.

“Certainly things were implanted or told to him that he then said, ‘Oh, yeah, I remember this,’ but it never originated with him. It came from what he was told or what was suggested to him during the interview,” Schultz said. “This has all the hallmarks of what the research has shown is a false confession.“

David Schultz is now a magistrate judge for the District of Minnesota. But years ago he was an attorney who represented Terry Olson through the Great North Innocence Project. Everything Schultz shared for this story is his own opinion as a former lawyer, and not his official opinion as a judge.

After the Dale Todd interview, things snowballed. The first autopsy report ruled the manner of death inconclusive. But Dale’s testimony was used to get a medical examiner to re-rule the death a homicide. She said she thought the injuries are more consistent with assault than with impact from a car. But years later she admitted in another court hearing that she changed it largely based on Dale Todd’s statements, which she called “newly discovered evidence.”

The BCA also reopened their investigation into Terry Olson and Ron Michaels.

“I was shocked that I was being interviewed again some 24 years later,” Terry said. “Everything had seemingly been taken care of in ‘79, and in fact I was very cooperative.”

Terry and Ron were indicted on murder charges by a grand jury. Dale Todd got aiding and abetting.

Chief Deputy Joe Hagerty talked to KARE 11 after the indictment in 2005.

“We felt they had a story they put together back in 1979, and fortunately people can remember the truth but not the lies,” he said.

Dale Todd was offered a deal by the prosecution: Testify against Ron and Terry in exchange for a lesser charge. Dale agreed.

‘I was the only one left’

Ron’s trial came first. Dale got up on the stand and started telling the last version of the story he had told the BCA agents. But at the end, he broke down. He said, “I didn’t do this. We didn’t do this.” The prosecutor asked him why he’d said they did it. He said, “Because I didn’t want to go to jail for something I didn’t do.”

Terry still remembers Dale’s words years later.

“At that point, we all should have went home,” Terry said. “We didn't.”

The jury acquitted Ron Michaels, but Terry’s trial went on as scheduled.

Terry said he was offered a plea deal before the trial. He said no.

Court documents show that Dale wanted to plead the fifth and not testify at Terry’s trial. But he was told he could be held in contempt of court - and possibly serve six more months in jail.

Other court records later revealed that Dale Todd received a visit in jail from Joe Hagerty, and one of the BCA agents, the night before he testified. He said afterward that he was afraid if he didn’t testify, his plea deal would fall apart, and even that he could be re-charged with murder in Jeffrey Hammill’s death.

“Dale Todd believes somehow that If he tells the truth, it's going to expose him to further criminal prosecution,” Schultz said.

In the end, he did testify against Terry.

Jailhouse informants also testified, saying Terry admitted to the assault while in jail. Innocence advocates frequently point to jailhouse informants as problematic, because the prosecution can offer them deals for their testimony. In Terry’s case, though, two additional jailhouse informants actually took the stand and said that he maintained his innocence while in jail.

In the end, the jury convicted Terry of Jeff Hammill’s murder.

“It's hard to find a word that explains what I felt during that trial,” Terry said. “It was scary. It was just terrifying. ... I think it turned into a situation where someone had to be found guilty in this case. And I was the only one left.”

Of all three men, Terry was the only one convicted of murder. He was given the heaviest sentence.

“You know, people would expect me to hate Dale Todd,” he said. “It made me cry … because at one point in my life he was my friend. And what they did to him was just as tragic as what they did to myself.”

Immediately after the trial, Dale Todd sent a letter to the court recanting his testimony, saying he and Terry were innocent. Dale said he testified the way he did because he was “afraid to go to jail for life for something we did not do.”

David Schultz wasn’t on the case at the time, but he said the judge sent the letter to both attorneys to let them decide how to proceed. Schultz said the defense went to find Dale Todd - but they couldn’t get him to talk. So they dropped it.

A decade behind bars

Terry went to prison and filed appeal after appeal, losing every one over more than a decade.

But after David Schultz came on board in Terry’s defense, the team found a new piece of evidence. Another recantation from Dale Todd. This one was different.

“People knew that Dale Todd had maybe some mental health issues, but what they knew was that he had anxiety and took some medication,” Schultz said. “They did not have anywhere near the complete picture of the seriousness of his mental illness.”

While Dale Todd was acting as the prosecution’s star witness, medical records show that he was falling apart behind the scenes. On Nov. 1, 2006, after he recanted at the Ron Michaels trial, a treatment note from a doctor and nurse who saw him while he was in custody said, “apparently today in court things did not go well.” The doctor wrote that Dale was having suicidal thoughts and believed he would be charged with first-degree murder. He was hearing voices. He told the doctor he was going to testify that someone was guilty when they were not, so he could get a “good deal.” But he said he had to tell the truth.

After that, another medical provider evaluated Dale and believed he had psychotic depression. He was not sure if Dale knew right and wrong, or what he was saying. The provider recommended a rule 20 evaluation. That’s where the defendant gets a psychological evaluation to determine if they’re competent to proceed with the case. He said “at least,” Dale Todd needed to be seen by a psychiatrist and get started on some meds.

The medical staff talked to Chief Deputy Joe Hagerty and said “a counselor had recommended a rule 20.” Hagerty said he’d have to call the DA. He called back and said, “Todd was not going to get a rule 20 at this time as he is a witness,” according to the court documents.

David Schultz found that none of this had been handed over to the defense during the trial.

In his appeal, he filed a Brady claim, accusing the prosecution of withholding evidence that could benefit the defendant.

That appeal was denied in July 2014. Terry had been behind bars for nine years.

Schultz said the judges in these appeals essentially kept ruling that any recantation by Dale Todd was “cumulative,” meaning it was nothing new. The jury in Terry’s case did know that Dale Todd recanted once. What would it matter if he did it again?

But Schultz believed this recantation should have changed the case.

“It's a statement made for the purposes of medical treatment,” he said. “It is entirely voluntary. It is unprompted. It's not made to law enforcement. And he, in the statement, he explains what he just did, why he did it, what the real truth is and why he's going to lie next time in the future and say they did it. All those things were unique to that statement, and it was different from all the other statements, and that was never turned over in discovery.”

A ray of hope

The fight wasn’t over. Terry’s team filed a petition with the federal courts for a writ of habeas corpus in 2015. In it they included multiple claims, including a claim of actual innocence. The judge denied part of the petition. But he also asked Terry to re-submit it, getting rid of some of the claims while keeping the actual innocence claim in there.

They had 30 days.

For Terry, this was a huge ray of hope - the first in a decade behind bars.

“My response when I saw it was very positive, which isn't a level that's hard to get to when everything else has been so negative to that point,” he said with a laugh. “So it didn't take much to get me to that level of being positive about it. I thought it was a huge breakthrough.”

David Schultz explained what it said to him as an attorney, and what he believed it said to Wright County.

“What that said to the prosecution is, unlike many, many habeas cases, we're going to reach the merits of this thing,” he said. “And the merits of this thing couldn't be separated from the innocence claim. That was the merits of it.”

Schultz said prosecutors were facing the prospect of a federal court deciding whether Terry had enough of a claim of actual innocence to grant him a new trial.

“That's what they were staring down the barrel of, and they didn't want to have the federal court answer that question,” Schultz said. “I believe that. They never said that. That's my opinion. But I believe that in my heart of hearts, they didn't want to have a federal court doing that.”

Terry’s team got to work amending the petition. But then, they received a letter. It was from the Assistant Wright County Attorney, Greg Kryzer. He said the habeas petition had caused his office to review Terry’s sentence. They’d like to offer a deal.

RELATED: New research shows prosecutors often fight winning innocence claims, offer deals to keep convictions

The re-sentencing

To understand the deal Terry was offered, it’s important to understand what happened with his sentencing.

When Terry was sentenced, it was according to guidelines from 1979, the year Hammill died. Both the defense and the prosecution agreed to that. Under those guidelines, the person would be sentenced to a range of time - and the Department of Corrections had discretion to set the exact release date.

Terry, his lawyers, and even the prosecution expected a sentence of 86 months. But the DOC sentenced him to 204. Terry’s lawyers believed the DOC calculated his criminal history score based on crimes that he was convicted for after 1979, while the case was cold. But in 1979, he had no criminal history.

Terry does have a record, including domestic assault, stalking and violating an order for protection. Those convictions all happened in the ‘90s and early 2000s.

KARE 11 reached out to the Department of Corrections about the sentence. They sent a statement saying that the 1979 guidelines provide for a departure from the normal release date matrix when the crime involves “great bodily harm.”

But the Wright County Attorney’s Office wrote David Schultz a letter, offering to release Terry immediately since he’d already served 130 months. They said this was “four years longer than Mr. Olson would have most likely received under the 1979 parole matrix.”

This deal was not an exoneration. It would be a re-sentencing. Wright County was admitting no wrongdoing. They were maintaining Terry’s guilt, and he would have to give up his appeal.

“You can have your freedom or you can continue to fight to clear your name,” Schultz said. “If you want your freedom, you're going to have to give up your fight to clear your name.”

Terry said the first thing on his mind was his mother.

“Her health was bad at the time,” he said. “And the one thing I did not want to happen in this was for my mother to pass away while her son was still in prison.”

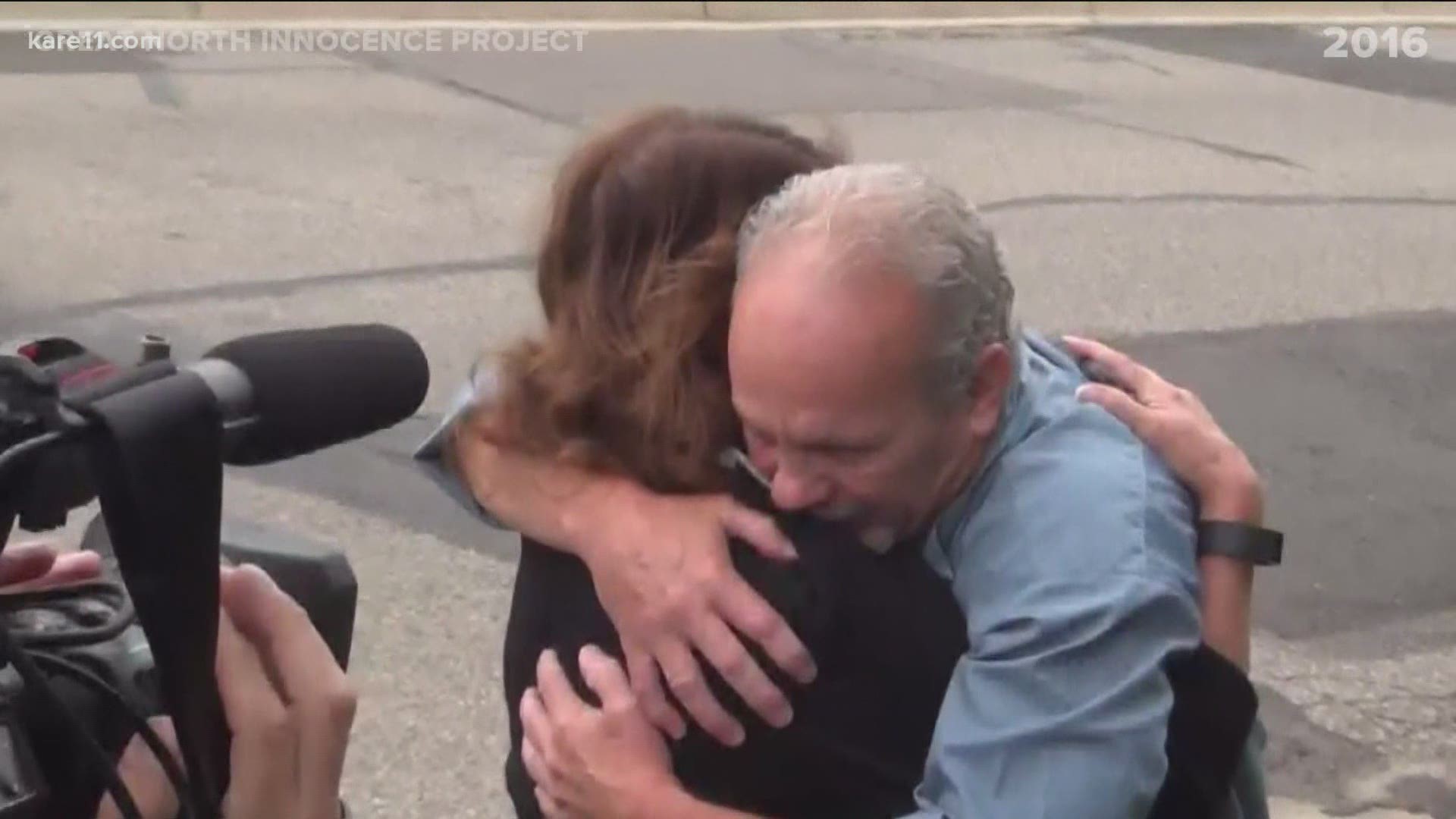

David Schultz and Julie Jonas, both working on behalf of the Great North Innocence Project, talked Terry through the offer.

“We laid out, ‘If you do this, this is what's going to happen,’” Schultz said. “‘You're not going to be able to sue for civil liability. You're not going to be able to have a piece of paper that says you are innocent. But you'll be out of prison in time to, for sure, see your mom.’”

On the other hand, if Terry turned down the deal, Schultz told him they did not know what the result would be. Even if he won his case, it could be reversed on appeal. And the process would likely take years.

Schultz recalled saying, “‘Nobody can make this decision but you, Terry, it is fundamentally personal and we will never second-guess your decision or criticize whatever decision you make.’”

“He asked us what we would do personally,” Schultz said. “And both Julie and I said we would take it.”

Terry didn’t buy that the Wright County Attorney was suddenly realizing there was a problem with the sentence. That’s because Terry had brought the sentencing problem up on appeal - six years ago.

“That was a very confusing time for me,” Terry said. “Did I want out of prison? You bet I did. But I did not want out of prison that way. I had already spent 11 years in prison for something that I didn't do. And I always felt that somehow the justice system would see through all this.”

Terry took the deal. He said one reason was to see his mom. The other was that he had lost faith.

Life on the outside

Terry has been out of prison for four years. His mother has pulled through so far but she’s still unwell. He visits her in assisted living now.

His first year out, Terry said, he had terrible anxiety attacks. He would shake violently and cry like a little kid. He couldn’t get his driver’s license back for six months. He couldn’t find an apartment for a year.

He’s now 62 years old and feels haunted by the conviction for this crime.

“I'm not in prison anymore,” Terry said. “But, yet, I feel like I'm still in prison. I own my own apartment. My space is bigger. I have my own shower and I can walk to my own fridge. Nobody's outside my door patrolling where I live or making sure I'm doing what I should be doing. Or what they feel they should be doing. But I'm still trapped. I'm just in a bigger space.”

Terry said his life feels “stagnant.” He lost his job and hasn’t found another one. He said he can’t get past the recruiters.

He has trouble being in crowds, and wonders if people recognize him. He wonders what people are thinking of him. What they aren’t saying.

“Some, of course, do understand, some don't,” he said. “Some have questions after questions, and even if you give them the right answers, they still have those doubts in their minds. And I can see that in people's faces and in their eyes when I'm talking with them.”

Assistant County Attorney Greg Kryzer and former County Attorney Tom Kelly, who just retired, declined an interview request for this story. Kryzer sent KARE 11 a statement from Tom Kelly saying in part, “Mr. Olson’s guilt has never been called into question. Every court that has reviewed this conviction over the past 10 years has agreed on one thing: Mr. Olson is a convicted murderer. Mr. Olson has never been exonerated for killing Mr. Hammill.”

The statement referenced overwhelming evidence against Terry, and the fact that he repeatedly admitted his guilt to other inmates while awaiting trial.

Kelly said in the statement that his office only agreed to shorten the sentence as “a matter of fairness and justice.”

Terry continued to fight in court for a while with another attorney, Erica Holzer, who tried to take his case to the United States Supreme Court. Under the law in Minnesota, Terry can’t seek federal habeas relief for violations of his civil rights by the Department of Corrections because he’s no longer incarcerated. And he can’t seek relief under a different federal statute, Section 1983, unless he can prove “favorable termination” like an exoneration. So because Terry took a deal, he lost his ability to even get in the door to try to make his case that his rights were violated.

He and Erica wanted to change this. They argued that the deal Terry signed was no deal at all - in fact, that it shouldn’t even be considered a voluntary agreement.

“A lot of these folks who enter these deals, they get their freedom in exchange for whatever they agree to, and typically their agreement to not sue the prosecutor or the county or state who is responsible for their incarceration in the first place,” she said. “And our position is that those agreements not to sue are invalid, and that the folks who are in most cases agreeing to those plea deals are doing so essentially under duress, under a veil of coercion, such that the terms of those agreements are unenforceable.”

The Supreme Court declined to review their petition at the end of last year. That was Terry’s last shot at legal relief.

‘A hard way to live’

It eats away at Terry sometimes, that he feels the men who took his life away got to keep living theirs, unimpeded. Joe Hagerty became sheriff, and then retired in 2019. Wright County Attorney Tom Kelly retired at the end of 2020.

“They get to, you know, spend their lives sitting on the lakeshore, fishing and doing all the things I should have been doing,” Terry said. “I won't be able to do that. I'm OK with just being OK now. That's a hard thing to say. It's a hard way to live.”

As for Dale Todd, he ended up pleading guilty to a lesser felony charge: aiding an offender to avoid arrest. He served just over three years in prison.

Neither Dale nor Terry have ever been convicted of another crime in Minnesota.

RECORD OF WRONG: After another man confessed to the crime, Hennepin County offered deal to preserve conviction